Thailand From the “Aid Villages”August 1990

Official Development Assistance (ODA), which is an agreement between governments, has often been criticized on various counts. Last year was the first time for any of Japan’s ODA to be channeled through Japanese non-government organizations (NGO’s). Although only one ten-thousandth of Japan’s official aid, 83 million yen, reached the towns and villages of Asia and Africa through NGO’s in the last fiscal year, I want to report from some of the “aid spots” in Thailand where NGO’s have been holding dialogues with citizens.

THOUGH THE TOWN BECAME CLEAN

Eighty kilometers north of Bangkok, I saw an example of typical ODA. Passing by a ruined pagoda in the center the ancient capital of Ayutthaya, I was startled to see a huge concrete building seemingly appear out of nowhere. It was the Ayutthaya History Research Center, which had just been completed on August 22. This project, which cost an astronomical 9.1 billion yen, was carried out jointly by the Thai and Japanese governments to mark their hundredth year of trade.

In the well air-conditioned interior, I came across a man explaining Thai history to his sons in front of a sophisticated, state of the art, audio-visual display. “I am very glad Japan understands our culture,” he observed diplomatically. “Actually, though,” he added, “a job training center would have been a little more useful than an expensive museum.” The man introduced himself as Somchai (46), director of a branch of Bangkok Bank in Issan, a regionin Northeast Thailand.

The annual income of a farming family in Issan is less than eight thousand baht (1baht= 6yen). It is well-known that many poor farmers there must leave their villages to seek work.

About two kilometers from the main building, on the site of a former Japanese village, is an elegant annex, built with the same ODA. Japanese tourists go there every day because the place is famous for Nagamasa Yamada, a hero in Ayutthaya in the seventeenth century.

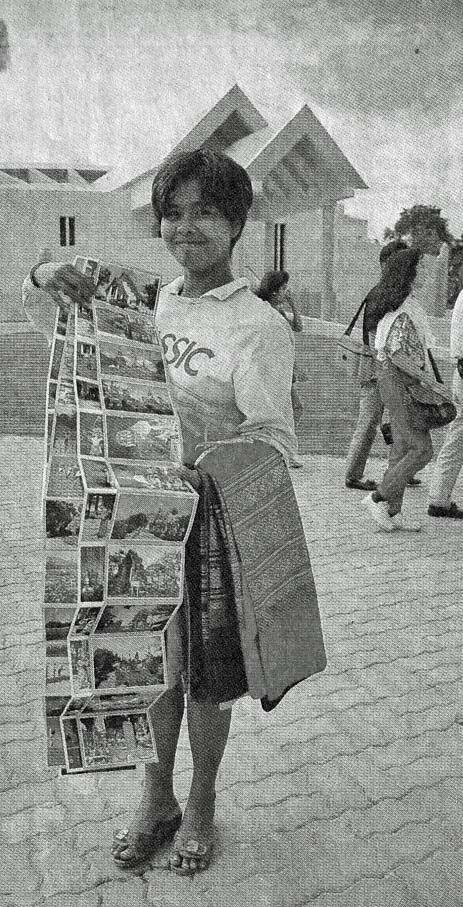

“Yasui yo! Sen en!” (Cheap! Only a thousand yen!) a girl with pieces of Thai silk and strings of post cards draped over her arm shouted to me. While I photographed the brand new building, she spoke with me, using all the Japanese she knew. Her name was Suanphun, and she was nineteen years old.

“Here? Yes, beautiful now. I can earn 70 baht a day — twice much as before, thanks to high Japanese yen.” Suanphun has been selling souvenirs to Japanese tourists for as long as she can recall, but seven or eight years ago, the exchange rate was not nearly so good.

She is the third of eight children. Her mother and two older sisters left home and are still missing. Suanphun quit primary school in the fourth grade and now look s after her five younger brothers and sisters while her father works at a rice mill for 2,000 baht a month.

“If I were able to work in an air-conditioned office…” she sighed plaintively. Neither Sunphun nor Somchai could identify with the ODA from Japan’s government. The aid spots where the ODA has been channeled through NGO’s to the ‘grass roots’ are in Issan, more than five hundred kilometers from Ayutthaya.

SELF-SUFFICIENCY HAS DOUBLE INCOME

“One day, a Japanese came to my house and bought all the silk I had,”said Mrs. Reu (44). “You are also from Japan, aren’t you? Why don’t you marry one of my daughters?” she joked. “You think I’m rich here,”I retorted,”but in Japan a bowl of noodles costs a hundred baht. You’d be a millionaire, too, if you went to Vientiane.” We both laughed together.

This is Sakhune Village in Northeast Thailand, where the former village leader has successfully pursued his own development projects since 1965. Banana and mango trees line the country roads, and mulberries grow thick. There is also a fish hatchery that Japan International Volunteer Center (JVC) built with Official Development Assistance (ODA). JVC agreed with his philosophy of selfsufficiency, as opposed to the central government’s encouragement of monoculture commercial production. The annual income of a farming family in this village is twice the provincial average.

All is not really rosy, however. “My two daughters married Bangkok men and will probably never come back,” complained Mrs. Kurem (46). Cities everywhere lure country people. “Last month,” Mrs. Reu added, “Japanese bought a rice field in the neighboring village, even though for us selling our land means selling our own legacy.” There is no guarantee that a farmer will not exchange his rice field for ready Japanese yen.

The village that JVC intends to support next is Muang Peck, one hour from Sakune, where clouds of dust rise from the distinctive crimson soil of the Northeast. “Toilets here aren’t flush, but they are much cleaner than those in Japan,” observed Akiko Hiruma, a 21-year-old Hosei University student. “I am disgusted with myself, because in my mind, I used to look down on this country,” she added. Miss Hiruma, who first visited the Northeast during a JVC study tour, said she wants to live in Thailand in order to understand much more about Thai people.

Muang Peck is quite different from Sakhune. The village leader, Boonmy (46), seemed a little reserved as he spoke. “We started a co-op eight years ago, but it went bankrupt because people didn’t pay, ruining the credit for shopping. Four years ago, we also tried to open a farmer’s bank, but no one would pay ten baht a day for the reserve fund.” A family’s annual income here is half what it is in Sakhune. Due to five years of continuous drought, the high interest rate of loans (5% per month, compounded) has driven the village people into a corner. JVC plans to open a rice bank which will allow a farmer to borrow rice seed with out taking out a loan.

When I heard that Japan’s ODA had sponsored a successful buffalo bank in another village, I decided to go there to see it.

NO TRACTOR BUT A BUFFALO

Pown Tuk village is located near a Cambodian refugee camp on the border in Northeast Thailand. Compared with the refugee camps, however, where aid from various countries is distributed by the United Nations Border Relief Operation, this isolated village is fighting against poverty without any help from the outside. Of the approximately three hundred homes in this village, only about thirty percent have water buffaloes of their own.

Last year, Nippon International Citizen Cooperative Organization (NICCO) under the direction of Kazuhiko Yamada (25), bought twenty water buffaloes for one million eighty thousand yen to establish a buffalo bank here. That amount of ODA (Official Development Assistance) could have bought only four tractors.

A farmer can borrow a buffalo for five years without charge. Forage and medical treatment must be paid by the borrower, but he may keep the calves that are born, usually one a year, except the first and third, which he must return to the bank.

One farmer, Seitanon, who has always used the bank, is very pleased. “I like these buffaloes better than ‘iron buffaloes,’he said,”because they don’t drink petrol, don’t break down, and their manure fertilizes the fields. The other day, when a buffalo gave birth to a calf, I was as happy as if I’d had a child myself.”

Mr. Yamada spent three months selecting the farmers who were the most trustworthy and who needed the loans the most. He submitted his project proposal to the Japanese Foreign Ministry last August, but the government didn’t approve it until eight months later, in March.

“The response was so slow,” Yamada explained, “that the farmers’ hopes and enthusiasm would have vanished, so I paid for the buffaloes with NICCO’s own funds. It would have been impossible if they had cost any more. Time seems to pass slowly here, but for something like this to be successful, timing is really important, you know.”

Mr. Yamada often leaves his wife and daughter in Bangkok and stays in Surin, an hour away from the village he is responsible for. The question which is always at the back of his mind is: “Why are circumstances so different for us human-beings (Thai and Japanese)?” As he seeks the answer to that question, he can be seen cracking jokes in his self-taught Thai in many of the villages along the border. His monthly salary is ten thousand baht, about sixty thousand Japanese yen.

NURSERY SCHOOL FOR THE FUTURE

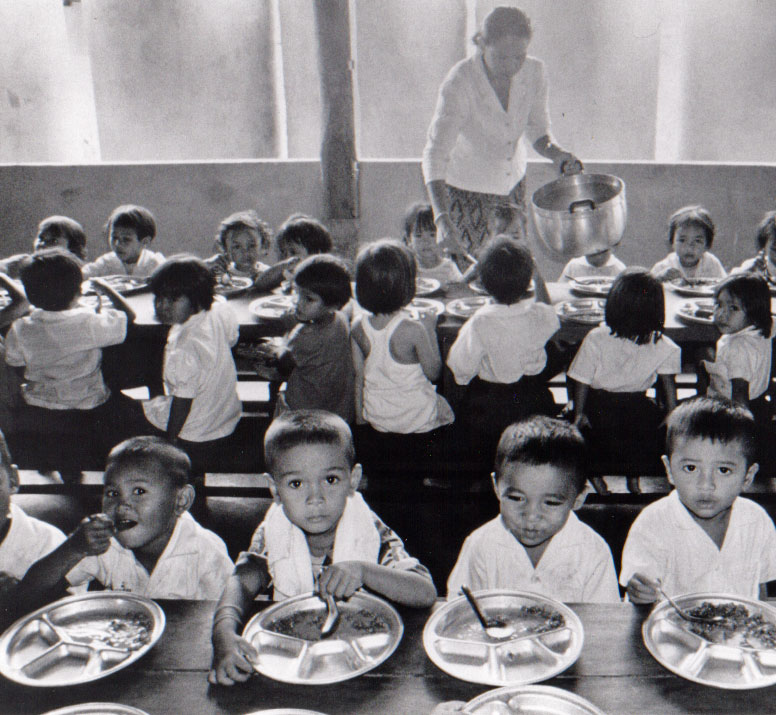

“What a strange sound!”I thought, as I listened to two farmers talking. Their conversation was in Khmer. I was in Swai village in Northeast Thailand, where Lao, Khmer, and Thai all live together. The Japan Sotoshu Relief Committee (JSRC) built a nursery school here last August. Half of the construction cost, totaling 2.5 million yen, came from Japan’s Official Development Assistance(ODA).

The classroom building and dining hall have bright white walls and high, triangular roofs. In the garden in front of these buildings, zinnia bloomed in a riot of colors…violet, maroon, yellow, and purple. Tiny children were merrily playing among the flowers on the new playground equipment. At present, one hundred and twenty-five children are learning greetings, songs, dances, and the Thai alphabet from five teachers.

“Khmer children don’t drop out of elementary school anymore,” explained Teerapol, a JSRC field staff member with sparkling, youthful eyes, in spite of his 44 years. “They can master standard Thai before starting school. Also their mothers can work harder. The average monthly income of their parents’is only eight hundred baht (about four thousand eight hundred yen). They have neither the means nor the time to educate their children at home.

Next to the nursery, there is a primary school where teachers and students started raising chickens from five hundred chicks bought with ODA given through JSRC last March. “I think ODA through non-government organizations (NGO) is a great idea,” said Prasert (50), headmaster of the school, “because it reaches directly to the place where it’s needed. When it comes through officials,” he continued with a smile,”the aid melts and trickles away just like the ice brought from town.”

The hens have increased to well over a thousand. The children are able to eat eggs and chicken for their school lunches, and the surplus is sold to cover some of the school expenses.

JSRC continues to assist the school with its own funds, however, because the school cannot by itself possibly raise funds for operational expenses such as teachers salaries and meals, amounting to four hundred thousand baht a year.Personnel expenses are not paid by ODA.

At the JSRC Office in Klong Toey, the biggest slum in Bangkok, I talked with the Director, Yoshio Hata (31). “It’s quite easy,” he sighed, “just to give people a finished product. We really have to think about what’s needed before we begin any project in a village. Even then, it’s necessary to give them a hand until they can make it on their own. We plan to turn that nursery over to the villagers at the latest when these children grow up, but……”

“EXPERIENCE” RATHER THAN MONEY

“Even if there are delays in this country, the people still say ‘Mai pen rai (No problem),’ don’t they?” laughed a Japanese staff member of a non-government organization (NGO). “I myself practice ‘When in Rome…'” Although he was at a construction site in Bangkok for one of Japan’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) projects, he was wearing sandals and the wrap-around cloth of a Thai peasant.

Early this year, Thailand’s construction boom created cement shortages, resulting in the delay or cancellation of some of the construction projects aided by Japan. ODA, however, is budgeted for a single year, without considering the real situation in the field. Unable to use the money they had been budgeted last year, one NGO announced the “completion” of its project in March, while another returned the money.

Phairat (40), president of a Thai-Japan joint venture, sympathized with the inability of NGO’s to deal with the money from the Japanese government. “You can’t meet the Japanese government’s expectations,” he explained,”unless you change contractors right in the middle of a project when things get delayed in this country.”

Floods have been very common in Bangkok for hundreds years, but today the city is flooded with cars. Because of the traffic, I was ten minutes late for my meeting with Dr. Srichai (41), Associate Professor of Chulalongkorn University.

“The disparity between city and village, the destruction of nature, and the traffic problem are all becoming more and more critical,” he began. “Rather than the simply giving aid based on economics and marketing theory, Japan should teach us what she has learned from her own experience about how to solve social problems caused by rapid modernization. This would be a blessing, and we would not consider it interference in the domestic affairs of Thailand.

In Patpong, the biggest red-light district in Bangkok, I had a drink with the staff member of a Japanese NGO who had just come back from a two-week provincial tour. “No matter how much the government gives ODA through NGO’s,”he said, “it will never work if we have to do things in their way. My salary? It’s only fifty thousand yen. That’s all, even though I work much harder than Japanese officials, and I am constantly on duty, 24 hours a day.”

It is strictly prohibited for NGO personnel to patronize Patpong. “But,” he explained,”I’m worried about some of the girls from the villages in my charge.” His excuse sounded a little like rationalization, but thousands of girls are working here far away from their villages. I know he was speaking from the heart.