Burma(Myanmer) Return of a Freedom FighterAugust 1996

The Turning Points

Rangoon has been as silent as the grave due to the purge by the military government, but on October 22nd 1996, about 500 students of the Rangoon Technical College went on a sit-down protest demonstration against the policemen’s assaults on students. By December 25, when I was writing this article, the other college students and general citizens joined the demonstration, and it has developed into a “wildcat demonstration” staged at an army’s unguarded moment and it is spreading not only in Rangoon but also to the local cities including Mandalay. There has not been such a large-scale pre-democracy movement as this for eight years since 1988.

Aung San Suu Kyi, a secretary-general of NLD, has addressed the absurdities in Burma to the consciences of people inside and outside the country at every opportunity since June 1996 such as at the general meeting of members and the party convention, which she called in spite of expected suppression from the military government. The students broke silence and went into action as if they responded to her those brave actions. But actually there was another significant event between these two turning points.

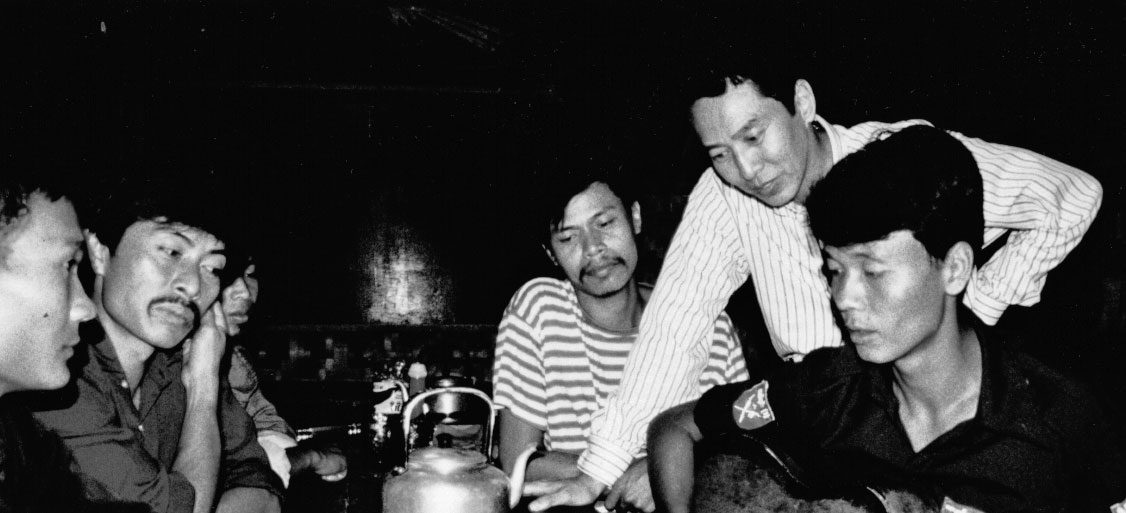

Activist Htun Aung Gyaw

It was the reunification of the All-Burma Students Democratic Front (ABSDF).The ABSDF had been split into two groups and gotten weak, but it united again on September 15th 1996 for the first time in four years. “One day, when I called Suu Kyi, she said, ‘Don’t worry about me. You should think about standing together before concerning about me. Now is the time to unite.’ That words made me do this work,” said Htun Aung Gyaw(43). He has fought for democratization of Burma for 22 years since he took part in the 74′ demonstration staged in Rangoon protesting that the military government made light of the funeral of U Thant, a former Secretary-General of the United Nations.

In 1988, when Tone Joe worked at a garage after five years imprisonment as a political criminal,’ the pre-democracy movement got so heated that the citizens rose in rebellion all over the country. On August 8th in that year, when he was leading demonstrators in the heart of Rangoon, he saw the National Army firing on unarmed demonstrators mingled with some children, and before his very eyes 24 young men died with their blood spurting out. He escaped the armed suppression from the military, together with eight thousand-odd students and general citizens, and they entrenched themselves in a jungle on the Thai border. On November in the same year, he founded the ABSDF in that jungle and he was elected as its first chairman. But both of the National Army and the Thai Home Office ran him down, so he sought refuge in the United States in July 1991. Four years later, his wife and children escaped from Burma and went to the U.S. He got a refugee passport issued by the American government and returned to the borders of Thailand and Burma in August 1996.

At ABSDF after five years’ absence

He saw the rapid development of Bangkok, feeling ashamed compared with that of his own country, but soon he left for the student camp. In the days of his chairmanship, there were 23 camps along the Thailand border with as many as 10,000 students, but ABSDF split into two groups a bit more than one year after he fled the country, and only Metamy Camp remains on the Burmese side in Kanchanaburi Prefecture, Thailand. The government will not allow traveling from the Rangoon side to that camp, where the first regiment of about 200 is stationed, even if it is “the Tourist Year of Myanmar.” As long as the world accepts the military government, there is no alternative to enter the liberated district of the pro-democracy groups but to enter illegally from Thailand. In rainy season a truck cannot pass through the jungle, so they had to walk for four hours in swamps and muddy streams from halfway. That is to say, these bad roads prevent the Burmese National Army from invading and enable the liberated district to be intact.

The Manapuro base of the Democratic Alliance of Burma (DAB), an organization of the Karen National Union (KNU) and other 21 anti-military government groups, fell to the National Army in January 1995, and the students stationed at the camps nearby dispersed to the Meatami or Pinmana districts. The total of the remaining students including those of the first and the sixth regiments is about one thousand. The other several thousands of students surrendered to the military government, emigrated to Thailand illegally, went to the third countries or died. They must have lost prospect of democratization, because the jungle life is very tough; the National Army attacks fiercely; and Thailand and other countries are indifferent.The Metami camp built in a jungle has a head office, a barracks, sports ground, houses, shops, a hospital, a school, a library and a temple. It’s like a village. The support from nongovernmental organizations has decreased sharply, so that they live self-sufficient lives by cultivating the fields and raising livestock.

The students who played central roles in pro-democracy demonstration in 1988 were in their late twenties at that time, so now they are in their early thirties. The infants held in female students are children of revolution born in the camp. As long as the political power is not transferred to a civilian government, they will remain stateless. It is remarkable that the morale in the camp is high despite these hard conditions, and that some young people are still coming to the camp. A rookie from Megui Tavoi said at a barracks that he couldn’t put up with the National Army, whose men came to the village and commandeered the villagers or plundered them of money and goods as if they owned the village. Meanwhile the students sneak into the villages which are located only eight kilometers away from Tavoi City and they work for the villagers’ health, education and welfare. They have no lack of supplies, because the villagers support them. In front of the students gathered, Htun Aung Gyaw started his speech with an introductory remark, “There must be some people who feel tired because of the long conflict,” he proceeded,”the Burmese pro-democracy movement has had a 10 to 14 year-cycle since the independence movement under the reign of England. Therefore, there is a chance of another rebellion in September 1999 or before that.

The ethnic minorities

The split of the KNU, the main strength of anti-government, and the fall of the Manapuro base has weakened the morale of the forces that are struggling jointly including the student organizations and other ethnic minorities. And the spreading ravages of battle are displacing many people from their home. President Bo Mya of the KNU said that it was split not because of inside discord but because of a plot of the military government. A monk called Tu Gana, who was allowed to use the former king’s palace by the military, tried to build a pagoda at a place near the KNU’s defense line and artillery position, So President Bo Mya opposed, “If you build a pagoda, build it in a scenic and safe place. Some enemy spies may come to the temple, concealing themselves in a crowd of visitors,” but Tu Gana built it at that place. After that, Tu Gana claimed again to build pagodas in the strategic points, so Bo Mya opposed again, and then Tu Gana started to criticize Bo Mya’s objection as suppression of notice that it was a trap. “The military will have no chance of winning with the normal tactics, so that they used the religion as a tool to split us,” the general said.

The Democratic Alliance of Burma (DBA) made it a rule that it would not have a talk on cease-fire with the military government unless the talk was collective bargaining held in the third country. The members, however, defected one after another and the KNU itself split up. As the result, it had to negotiate individually. But peace has not come even after the cease-fire agreement. On the contrary, the sufferings have increased. The national army commandeers the villagers or forces them to move out of their village. The army keeps invading to Kareni, Kachin and other states after the cease-fire, and it prohibited those states from collecting the state taxes, forming an organization and gathering. On top of that, the army doesn’t allow those ethnic groups to take educations of their own languages and cultures.

From the news report, people may take it that all ethnic groups concluded the cease-fire agreement with the military government, but some strong ethnic minorities launched the counteroffensive, because the government never stopped despotism after the agreement. “We ceased fire to have peace talks. But if there is no talk, ceasing fire makes nonsense.” Bo Mya’s mind has changed back to his initial one. Bo Mya refused to deal with the military government that proposed only community development, setting a political settlement aside. He saw through the government’s intension long ago that when roads were built, it would control the communities by force of arms and exploit their natural resources. “Besides, community development will give business chances to the leaders. Once they begin business, they will lose interest in politics and their relation with the citizens will be severed. Actually some leaders who tied up with the military government became rich and bought a house and a car, but the citizens don’t have such business chances, so that they harbor ill feeling against those leaders. Our unification fell into pieces,” said Bo Mya with good judgment.

Inside the country

As a result, many people are fleeing to the Thai border. Before the Manapro base fell, the number of refugees at Bargaro refuge camp two hours away from Mea Sot to the north was around eight thousand, but the number of the cases where a whole village comes for refuge has increased and in August 1996 when I visited its number of refugees reached 25,199. Abraham (42), a displaced person of Karen tribes, guessed why they were assaulted. “They don’t like Christians. I worked for a Christian organization. That’s the why.” The National Army and the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army, a seceder from the KNU, were looking for him. He heard them calling his name in a cave where they werehiding. He and his family were long in escaping from the village that was set on fire, and his oldest daughter died and the other four family members were badly burnt.

Htun Aung Gyaw gave encouraging words to them, who were scratching itchy keloid. “If you give up now, the army will continue tyrannies to the generations of your children and your grandchildren. We should fight back as long as we live, with the consciousness that we are fighting for truth and our right.”A refugee from Tavoi district vented his anger against the National Army. “They come in our houses without leave and take away everything including clothes, even pots and kettles. They are no other than a gang of housebreakers.” The army sometimes starts a fight to make a village deserted. If a village pays 60,000 kyat (100 kyat is about 65 yen), the village may escape damage. But there are many cases where a village was burned up because it didn’t have money to pay, such as Chotaeniji village of the Mon.

Many villages are also forced to move. In May 1996, 96 villages of the hill tribe Karenee, leaving their fields and livestock, were forced to move to flatlands, the living conditions of which were completely different from those of the hill. The National Army took their villages as strategic villages of guerrillas and tried to get rid of them completely. According to the refugees, if a village doesn’t pay the sum of money that is multiplied 2-3000 kyat a day by the number of persons and the number of days when the National Army comes to a village for commandeering, the army takes them forcibly. I met a victim of the army’s tyranny at a hospital in Thai territory. He told me his experiences. “The army took me away, though I had malaria and was put on an intravenous drip.” He was forced to carry a burden of 35 kg on his shoulders. He collapsed on the 13th day. Then a soldier of the National Army hit him again and again and threw him away over a precipice because the soldier thought he died. A friend of his who escaped took him to this hospital, spending ninedays. But his malaria was aggravated, his ribs were broken, he lost his eyesight, his legs crooked and he couldn’t stretch them at all. For all his anguish, as if he was carrying out his duty as a survivor, he told me through his tears that when his friend couldn’t walk because of fatigue and poor meal, the army shot him to death.

In a suburb of Mea Sot there is a restaurant which doesn’t serve good food and whose employees practice prostitution. A waitress (17) of the restaurant hasn’t seen her family who live at a refugee camp for a long time, because she thinks her job is a ‘disgrace to her tribe.’ The army tortured her parents to make them tell where their son was. He was a KNU soldier. Then her whole family fled to a refugee camp in Thailand, but the rations distributed at the camp were not enough, so she came here. All of 12 girls here are such Burmese refugees. Her income from the illegal work, she has no alternative, only a hundred baht (about 420 yen) a customer. The military government tries to govern the country by force and wade through the financial difficulties by making the people to give their labor, money and goods to the government. But, the people’s not supporting the military government is the very cause of every trouble.

Foreign Pressure as a resort

Burma citizens entrust their hopes to pressure from foreign countries, but there are indications that not only ASEAN countries but also Japan and Western countries are supporting the military government. The main causes are 1) foreign governments and companies are going after the virgin market of Burma that will be helpful to business recovery in economic activities, 2) they are soothing the military government for fear of Sinicization of Burma, 3) they believe that economic development will prompt the country to democratization, and 4) they don’t have a right understanding of the actual conditions in the country where the citizens have to give the highest priority to escaping from poverty.

Htun Aung Gyaw said, “Thailand and other ASEAN countries are coping with the army, a traitor to our country, because they can buy our natural resources and labor at lower price, taking mean advantage of Burma.” In regard to the movement to recognize the military government on the pretext of Chinese advance into the south, “Even if Western countries and Japan expand their business to this country under these conditions, Burma has already been the same as or worse than China in respect that there are no human rights nor freedom,” he pointed out the quibble of big powers. While I was visiting the border, a Thai newspaper reported as big news that Ms Megawatti’s office in Djakarta was set on fire. “Some people say that if economic development makes progress, democratization will also advance, but how about Indonesia? It has developed enough to build a plane,” he argued.

But still there is an opinion that the military government is suitable for Burma because the dictatorial state power improves the efficiency of development in a developing country. “Military government seemsto be efficient because the army acts on orders, so even if a wrong order is given, no one can disobey it. That’s an army. Burma became the poorest country in the world in the 26 years of Ne Win’s dictatorship. It has already proved that idea wrong,” he dismissed the opinion. Some analyzed why Burma under Ne Win’s regime didn’t develop so much as Japan under the dictatorial regime of the Liberal Democratic Party or as Korea under the military government. They said Burma didn’t have a geographic feature to “benefit” from the Cold War between the East and the West and it could close the country. Some said that the government had to bear a burden of the ethnic minorities’ struggles for independence, but other governments didn’thave to bear such a burden. And some have cool opinions that whether Burma can have foreign companies and tourists come to Burma depends on not whether the regime is democratic but whether it is stable. But Htun Aung Gyaw said, “There is no stable regime without corruption. The foreign governments and companies will be sponged on for bribe, so that business and tourism will not be helpful after all,” he asserted. Also he added confidently, “A conscientious person would change his way to cope with the military government, if he realized how severely the citizens are oppressed.”

Reunification of the ABSDF

Htun Aung Gyaw found a new meaning in Aung San Suu Kyi’s words ‘the time of reunification,’ when he saw the actual state of affairs in Burma, which the refugees complained of, and the despotism after the cease-fire agreement, which the ethnic minorities were indignant at. Motizon, a chairman of one of the two groups of once-split ABSDF, said looking back, “The main cause of the split was a suspicion that there was a spy inside the ABSDF rather than discord of opinions on a policy or strategy.” The army infiltrated several secret agents. The agents supported different leaders with opposing opinions, gave names to the groups, forced the members to belong to one of the groups, and started quarreling. “At that time I didn’t have enough experiences, and I fell into the trap.” When the first chairman broached the subject of reunification, Motizon said, “I will not make you lose face. It’s not so big problem for us to send many representatives.” He was looking hard at their common goal.

Nain Aun, a chairman of the other group, said, “Time removed each other’s distrust.” Time weeded out the students except the dyed-in-the-wood fighters for democracy toone-seventh to eighth of the original members. “Our split had a bad influence on the ethnic minorities and the students within the country. It only made the military government pleased.” Nain Aung has also realized the trap set by the military government. A month after Htun Aung Gyaw’s groundwork, the two groups held a general meeting and united afresh, electing Nain Aung as a new chairman and Motizon as a new vice-chairman. But just before the general meeting, a discouraging false rumor that many students stationed on the borders pledged allegiance to the military government was circulated. The truth is the state-operated TV station gave an exaggerated description of the fact that 20 students surrendered against their will because their wives and children were taken as hostages. The impact of the reunification was so big that the military government tried to ruin it.

Unlike in 1988

This event must have greatly encouraged the students in the country who have lost supporters. But I will not mention its relation of cause and effect because it goes against the purpose of the report. While the military government is deporting the foreign journalists, the ABSDF tries to strengthen the link between Burma and the world, making the most use of the underground and the internet. The information I’ve gotten from October 22nd 1998, when the students staged a demonstration for the first time in eight years, to the deadline for this article are as follows: 87 students out of the arrests have not been released yet; two NLD members were put into jail and sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment without being on trial; a cleaner who is supporting the NLD was beaten to death; there were demonstrations in Molemen and Taungee; in Rangoon the junior high schools and schools of higher grade were closed and the students in dormitories were forced to go home; checkpoints are set up on the roads and bridges to the city and 15 tanks are disposed within the city; telephone connections are not good; the local currency ‘kyat’ declined sharply; the citizens are in a hurry to exchange kyat into dollars and hoard up rice.

“There is a powerful party in the country now unlike in 1988, and the students on the borders reunited and have strengthened their solidarity with ethnic minorities and pro-democratic groups abroad. If these two forces inside and outside the country work together, we will be able to do better than in 1988,” said Htun Aung Gyaw when we parted at the airport lobby.Then he left for America where he fled to, saying “See you in Rangoon!” The day when I can see him again in Rangoon is approaching steadily.