Cambodia It was still a battlefield thereAugust 1991

Battambang, blessed with abundant natural resources, Banteay Meanchey, flourishing with Thai trade, and Siemreap. with the world treasured ruins of Angkor Wat, are the three finest provinces in Cambodia. These provinces are veryimportant economically, culturally, and now strategically as well because they have been liberated from the three parties. There are also serious problems for Cambodia to be found here that we cannot see in the central region around Phnom Penh. Stopping over for two nights, I went all around Battambang.

VILLAGES IN BATTLEFIELD

Just north of Battambang city on the way to the front line, there are uncountable nipa-palm-roofed huts covering the foot of Mt. Svay (Mango Mountain). Even after the ceasefire of May first, 46,934 displaced people in 8,834 families from Banteay Meanchey Province directly to the north are still subsisting in nine camps such as this one.

The roars resounded but not from thunder. The shelling echoed in the Bovel County Office, one and a half hours north northwest of Battambang City, eighty kilometers away from the Thai border.

“What ceasefire?” Mr. Ho Phino (38), leader of Bovel County, asked sarcastically. “Since that day, the first of May, more than eight hundred shells havebeen fired at Kardol Tahen and Amphoe Pradam [about seven and twelve kilometers respectively southwest of Bovel]. When the people came back to plant their rice seed at the beginning of the rainy season, the shelling intensified. Just the other day [September 18, 19], Khmer Rouge attacked Ann Runrune. They killed two villagers and injured four. They stole ducks, hens, rice, a video player, and a hundred thousand riels. On top of that, while they were withdrawing from the village, they laid new mines!” From those villages transformed into battlefields there are 1,458 displaced people, 218 more than at the date of ceasefire. Despite the increase, emergency aid has remained fixed at the same amount.

“This way, Sir,” Rui Nou, a twelve-year-old boy of Sune Suran Village, guided me to a big puddle created by one of two rockets which landed in the village the end of September.

He showed the scar on his shoulder caused by a rocket fragment. That piece had pierced through the wall of his house which stood only thirty meters from where the rocket hit. His father brought out what was left of the rocket to show me. The aluminum alloy tube was split open just like an empty banana peel, but the rocket was still distinguishable, 107 mm, made in China.

The people of Ta Hen Village, seven kilometers to the south, evacuated to Suue Suran Village. Mrs. On Voeun (30) has no left leg. “It was three years ago,” she explained, “just after I brought my husband back from the hospital. He had stepped on a mine. Just five days after he returned home, when I was going to the rice field, I stepped on one too……” The amputee parents have three children, the eldest of which is an eight-year-old son. “We haven’t gone back. We’ve neglected our rice field for three years.” They are living on rations brought once or twice a month by a NGO and with the help of their relatives.

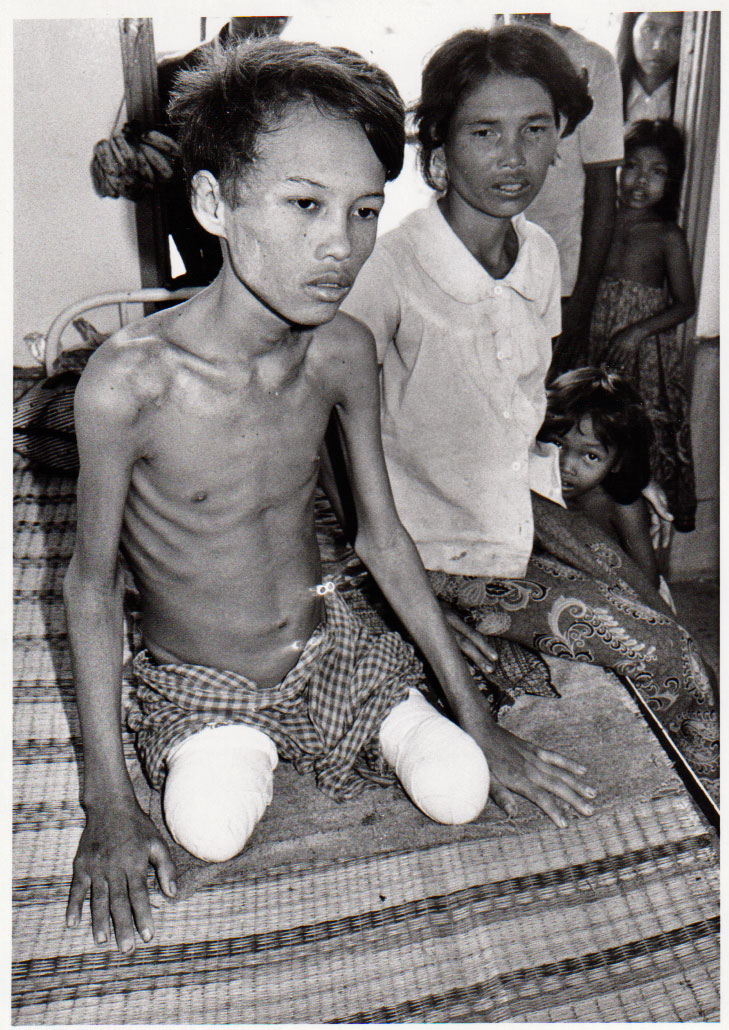

Mongkol Borei Hospital is still called “Muntipen Japon.” It was built with Japanese donations in 1963, and Japanese medical staff were stationed there until the Pol Pot year. Injured patients are often carried there, even from several hours away, because the facilities are better than elsewhere. The hospital treated seventy-nine wounded in March and thirty in August. Obviously, all the patients hospitalized there had stepped on mines after the May first cease- fire. According to the International Red Cross, there are more than five hundredthousand land mines buried in Cambodia, more than anywhere else in the world.

From the ceasefire until the end of August, Battambang Province recorded these horrors of war: eighty-three cannonades (more than five thousand shells), twenty-nine land mines detonated, six attacks on villages, sixcases of plundering, seven cases of kidnapping, thirty-three civilian fatalities, forty-two civilian injuries, and one hundred eighty-seven burned down houses (Statistics from the Battambang’s People’s Committee).

COLONEL

On the way back to Battambang, we dropped in at a post with heavy machine guns set along a trench. “Combat at the present time is intended to protect the people, not to kill the enemy,” explained First Lieutenant Chan Pouch (25). When Heng Samrin’s army withdrew to defense positions in accordance with the cease-fire agreement, he explained, Khmer Rouge attacked even more aggressively, storming those posts which the government’s army had seized before. In what used to be a safe area, farmers are now suffering from Khmer Rouge abuses.

First Lieutenant Pouch has faced the Khmer Rouge on the front lines since 1984. He disclosed his misgivings about the UN plan. “Although the agreement calls for a seventy percent reduction in weapons, I don’t believe Khmer Rouge will ever honestly do that. If ordered to, we will cut our weapons, but, mark my words, if the UN army doesn’t search every nook and cranny of the villages for Khmer Rouge cheating, the results will be horrifying.” As if obeying the second hand of my watch, the shelling continued seedily at a frequency of three times a minute. After returning to the town in the evening, I went to Battambang Garrison Head Quarters to be briefed on the general war situation. “Welcome!” shouted Colonel Van Sophath as he shook hands with me. “I’m delighted to have you see the real situation for yourself. The reason Pol Pot signed the ceasefire agreement was that we controlled all seven strategic posts of Battambang at that time. It was a dirty maneuver to regain those positions during the ceasefire. Clearly, they intended to break the agreement from the beginning.” He analyzed the plotting that the preceded Pol Pot’s agreeing so quickly and unexpectedly. “As evidence, there’s information that a hundred fifty-eight China-made military trucks went into Pailin, a Khmer Rouge controlled area, two weeks ago [20 September]. We are going to present the photographic proof to the United Nations.”

In 1968 Colonel Sophath joined the Khmer Rouge which was supporting Sihanouk’s anti-government stand. In 1975, when Pol Pot was starting to control the Khmer Rouge with absolute power, he tried to desert, but he was arrested and imprisoned. In 1979 he escaped from prison to Vietnam and became one of the founders of Heng Samrin’s liberation army.

Col. Sophath is also pessimistic about the United Nation Peace Keeping Force. “The Khmer Rouge never stay in one place. They will hide their weapons in the deep jungle, on the mountain tops, and in underground fortresses. It’s impossible to enforce the seventy-percent weapons reduction. High-tech mine detectors can’t be used here because they react to the fragments of the innumerable bombs exploded in the area over the past thirteen years. Another problem is that the Khmer Rouge not only scatter their land mines on the ground but also attach them to the trees. Some are even made of bamboo. Foreign soldiers won’t be able to deal with the Khmer Rouge, and, of course, the troops of Son Sann and Sihanouk are virtually helpless against the Pol Pot forces. We are the only army who can fight the Khmer Rouge, but we have agreed to follow the UN plan. It’s obvious, as plain as day, “Col. Sophath continued earnestly during supper,” that war will not end even after the general elections.” I had the impression there was still more he wanted to say.

RETURNEES

Eight years ago Mr. Meas Sarun (40) and his family went to SITE 2, the refugee camp controlled by Son Sann’s Khmer National Peoples’ Liberation Front on the Thai border. He returned to his old house in Roung Ampil Village, but he stayed only two days.

“We didn’t have enough to eat,” his wife, Mrs. Po Phaly (40) said calmly,”but we had heard that once you got in the camp, everything was available.” Only the parents and their nine-year-old son returned. For the four other children who were born in the camp, this would have been their first time to see their father’s land. Nowadays, half of the population of the border camps is under twenty years old and totally ignorant of Cambodia just like these children.

“What on earth is that man thinking?” grumbled Meas Sarun’s mother-in-law who never left the village. “Now, he’s gone back to the border again.”

Many refugees have returned before the UN repatriation program officially starts, but there are no statistics. Many in the camps continue receiving rations for family members who have already returned by putting their names on the registration anyway, quite of few of those who hove left, come back to camp if they lack food or medicine.

“In May the rice ration for one person was reduced five hundred grams,” was Sarun’s reason for returning. They have three hectares of rice field here. “When we had to plant the seed, there was no rain, and now there is flooding,” Phaly complained. “It’s no damn good!” Their three oldest children are school age but don’t attend school, even though it is nearby. “We can’t afford the five hundred riel (about 60 yen) cooperation fee,” Phaly said, excusing herself. Her eyes were so hollow.

Sarun returned to the border carrying two bottles of homemade dental pain-killer that he himself had prepared from roots and herbs. His mother-in-law was very up set with him because even if he sold all the medicine at a good price, he would only get a thousand riels.

THE OPENED WINDOW TOWARD THE WEST

Sisophon is the capital of Banteay Meanchey Province, but there is no hotel at all. We stayed the night on the third floor of the governor’s official residence. The governor, Mr. Ith Loeur (40), had been an official government interpreter until Banteay Meanchey separated from Battambang in 1989. He speaks English, French, Thai, and Khmer fluently. His appearance is very neat, and he speaks like the representative of the central government whose pronouncements before the UN have recently become vague and indefinite.

“We had started discussions about the reopening of the border independently of the May first ceasefire, agreeing with Thai ex-prime minister Chatichai’s policy ‘from battlefield to market,'” he said, referring to the border between Poipet and Aranyaprathet which had been closed for sixteen-years. “In fact, we had expected the border to open on April 14, but the recent Thai coup delayed that to May 15.”

Asked why they wanted the border opened, he answered, “We know that liberal ideas and new social problems will come in as well, but still the good points outweigh the bad. The people won’t accept what’s not good,” His answer was so sensible.

Would there be any appeal to the West? “Our government has labored to defend the people against the brutalities of Pol Pot and to raise the standard of living rather than to practice a so-called ‘ism.’ The current Cambodian admini-stration seems about sixty percent socialist and forty percent capitalist now,but the day is coming soon when we’ll have to reverse these proportions. For example, we have allowed the owning of and dealing in real estate. We have auth-orized western imports from places like Singapore and Thailand.” He said this in a tone that implied he wanted to erase the color of socialism.

To my rather crass question about freedom of speech, he responded,”If I said there were no control over free speech, I’d be a liar. This is still a very delicate time, and if we make mistakes again, we won’t be able to rebuild our country. As you have seen, our country has been devastated by war. Our people are too poor to have enough education to realize how sublime the concept is. If you try to achieve that in too short a period, you will be ‘Pol Pot,’too!” he said, concluding with a black joke.

A prefectural officer got a lift our car from Sisophon. The night before, this small middle-aged man had brought a candle to my room and showed me a photograph of a driver I remembered seeing. “He is my old student,” he said proudly. Then he introduced himself. He had been a ‘professeur’ of geography at Kandal Prefectural High School. The driver in the photo is well off in Phnom Penh because of his English ability. Suddenly, the man handed me a piece of paper. Although the English was full of mistakes, I understood:”I am too poor to send my children to school. Could you give me five dollars please?” I had heard that an official’s salary was very small, but I was shocked by this miserable-looking ‘professeur’ who timidly watched my reaction. Unlike the Khmer in the refugee camps, the Khmer inside Cambodia had up until then seemed to me to have a sense of pride and dignity.

BORDER MARKET

In splendid contrast, these people were energetic. As if not minding the muddy red soil of Route No.5, farmers vigorously pushed their bicycles loaded as full as possible with baskets, mats, rice, live chickens, pottery, and more. At the Poepet Market on the border, one basket could be sold for ten baht = four hundred fifty riels. That would buy a bowl of noodles for a Thai, but for a Khmer it was equal to the daily wages of a government employee.

It was Sunday. With many day-trip shopping buses running from Bangkok, a great number of Thais march into Cambodia through the gate modeled after the towers of Angkor Wat. There are Cambodian and Thai check points each about 150 meters from the O Chvou bridge, the geographical border line, with the area between a neutral zone. By paying five baht, a person can receive a “Frontier Pass” valid in the other country until four o’clock the same day. There is also a comparable market on the other side of the border at Aranyaprathet, Thailand. Actually, the prices are identical by agreement of the two governments. Thai people want to enter Cambodia, however, because “We came to the border on purpose.”

Poipet Market which started at the same time as the border reopened on May 15th has almost three hundred shops in twelve long buildings with no walls. Nevertheless, it was stuffy inside with the humidity from the dirt floor and the body heat from the throngs of customers. “Those selling for five hundred baht are counterfeits, but these watches are all real ‘SEIKO,’ so they cost eight hundred ten baht each.” Mr. Yun Chhen (43) a Khmer shop manager is proud of his merchan-dise. He is an overseas Chinese and writes his name in Chinese characters. During Pol Pot’s time, his shop was confiscated, and he was forced to be a truck driver. “I like the coming of peace. I want to run a rice mill and make a profit here,” he said, smiling like a fish returned to water.

More than eighty percent of the customers are Thai. How astonishing to be able to window shop for a “STEREO” cassette tape player with only one speaker, a “NIPPON” radio of unknown nationality, and a calculator with “Made in Japan” written in an unusual cursive script. Even imported goods such as industrial products, liquor, and cigarettes are cheaper in Cambodia than in Thailand, probably because Cambodia doesn’t have a domestic industry to protect with high customs.

I found Soviet pumps displayed next to Chinese electrical tools. A pump selling at a fixed price of fifty-five roubles or ten thousand riels in Phnom Penh costs eighty-three thousand riels here. Even at this price, it is one of the biggest bargains for Thais. As a result, the pump is often in short supply, and the price doubles in Phnom Penh.

The number of Thais crossing the border is twenty thousand on weekdays, forty thousand on Saturday, and fifty thousand on Sunday. The Cambodian Immigration Office earns a lot of revenue simply from the five baht visa fee of each one. Unlike the situation previously with the black market, Cambodia can now use a sliding scale system to clearly impose customs duties ・・・nearly forty percent on cosmetics and bicycles, twenty to forty percent on electrical appliances, five percent on medicines, but nothing on agricultural chemicals and fertilizer.

The Phnom Penh government makes a profit of more than thirty million baht a month from customs duties here.

AN UNEQUAL TREATY

I had planned to enter Thailand and to continue coverage of the Khmer refugee camps, but the Thai immigration officer refused to admit me to Thailand. “No, you can’t! No Japanese can come in. Only Khmer can enter on a day-return. We don’t have the stamp for your passport here,” he said with an air of finality. Mr. L of the Cambodian Foreign Ministry began to talk with him on a practical level as a fellow officer.” We don’t have such a stamp here either, but you often send foreign journalists to us, and we have never sent them away. Actually, we have even issued their visas after their arrival in Phnom Penh. Why don’t you ……?” he reasoned. Since the Thai government doesn’t require a Japanese passport to have a visa at all for a stay of less than 15 days, it was obvious that Bangkok looked down on Phnom Penh. Mr. L became upset at this “unequal treatment.”

The immigration officer was a Thai, however, and Thais don’t like quarrels. “All right,” he said. “You can enter if you leave your cameras and passport here.”This meant that I could enter the same as a Khmer. We had two hours in Thailand to enjoy a Coke with crushed ice and a delicious Thai lunch. When I though about the long return trip ahead of us, driving down that bumpy road for two days back to Phnom Penh, only to return here via Bangkok three days later, I felt the reality of “the border.”

AHEAD OF THE PEACE AGREEMENT

On the tenth of October, the day before leaving for Japan. I was scheduled to interview the person in charge of United Nations Border Relief Operation (UNBRO). There was a sudden coup, however, at SITE 8, the camp controlled by Pol Pot party, and he was fully occupied with the emergency. The Khmer Rouge had tried to dispatch their aggressive leaders to the camp in order to repatriate the refugees themselves without complying with the UN program.

Just before this article went to press, I made international calls. A UN fieldofficer(44) gave me the latest news from the border area. A thousand new- arrivals had fled into SITE 8 because of severe malaria, and the population increased to forty-four thousand two hundred and fifty seven (reported on 15 November). “Even Pol Pot cannot wipe out the mosquitoes,” he joked.

Although there were parades in the camps on 23 October celebrating the signing of the peace treaty and on 14 November celebrating Sihanouk’s return, there is anxiety that “No Repatriation” demonstrations will break out in the same camps when Mrs. Sadako Ogata, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees comes to visit the border in January. The more the peace talks evolve, the greater become the worries about poverty and discrimination after the refugees go back. No refugee of any party is wholeheartedly happy at the prospect of repatriation.

An NGO staff member(29) in Aranyaprathet offered impressions drawn from his own interviews of the people in the camps. “Although eighty percent of the refugees agreed with the UN plans, many of them say they want to be sent back, not to their home towns, but to Battambang. Most of them think that if they work in the rice fields in the territory controlled by the three parties, they won’t have to worry about persecution, and that they will be able to escape to the border once more if something terrible happens again.”

According to Mr. Wititt(38), a Thai reporter familiar with three parties’ territory in Cambodia, Pol Pot is offering presents like a mine-swept rice field complete with water buffaloes, in order to lure refugees into his “liberated area” before the UN repatriation starts. He sees it as a contest for refugees with the United Nations which plans to provide rice seed, plows, and mosquito nets. There was a momentary delay in the telephone connection, and then I heard Mr. Wititt’s characteristic suppressed laugh, “Most of the refugees are farmers, you know. Anyway, they don’t care whether it is the UN or any one of the parties, just as long as they are able to make a living peacefully.”