Laos & Vietnam Village of Stag Beetle RushAugust 2000

“A business” triggered by Japan

—in Xieng Khouang Province

Our vehicle–a high-slung military truck just managed to go on the red-clay road, which was very sticky because of rainy season. The truck passed through the jungle, making ruts 50cm deep in the road and scraping its body against trees on the both side of the road. After driving about 40km toward the Vietnam border from Phon Savanh, the provincial capital, we arrived at Nasan Village that is bustling because of a rush for stag beetles.

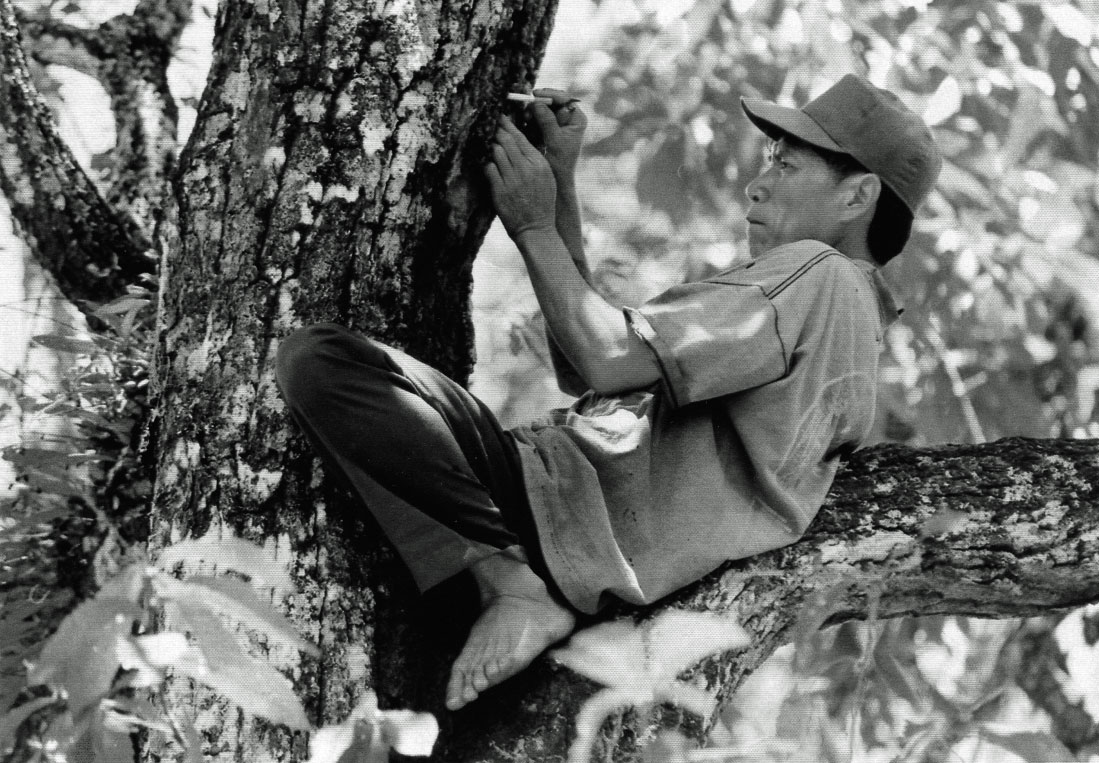

A local farmer, Shidar was climbing a big oak tree called “Sir” easily with a cigarette in his mouth. “I found a she!” he shouted, when he went up to a height of about 6m. Then he stuck a knife in the bark humming a tune. He widened a hole where the stag beetle was sleeping, and put the cigarette into the hole to smoke the stag beetle out. He did not have a cigarette in his mouth for nothing. Smoking a stag beetle out of its nest is his way of capture. It took only five minutes for him to catch the jet-black beetle. He threw it to his partner and said, “There is a he, but it’s too small. Nobody wants to buy a beetle below 6cm long. So I won’t take it.” Near the tree there were two trees cut down by the roots. “There are only five men including me who can climb up a tree to catch stag beetles. The others cut down trees to catch them,” he said with a wry smile.

Dorcus grandis? stag-beetle fanciers slaver after

More than a thousand of stag beetles captured in this village were brought to Japan last year alone. The import of stag beetles has been banned on the grounds that foreign stag beetles will harm the crops and disturb the ecosystem. But the Plant Protection Law was amended in November 1999, and the import of 44 species of beetles was permitted.

Above all, Dorcus grandis, the biggest species, is slavered after by stag-beetle fanciers. Before the removal of the ban on importing Dorcus grandis, it had been traded secretly at a high price. Here Xieng Khouang Province is its habitat.

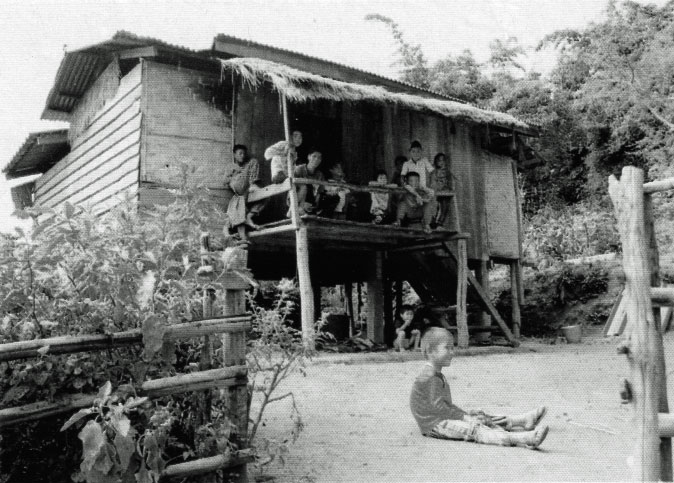

Thirty times as much as the income from farming

Coo Village, where Shidar lives, is about 5km distant from this wood and the nearest to there. In this village more than 80 percent of the 55 farming families are intent on catching stag beetles, and no wonder. Their income from farming is about 700 yen a month, while this side job brings them more than 30 times as much. The stag beetle, however, is not regarded as a special insect in Laos. They are roughly called “tree bug” or “pliers bug”. But in Nasan Village, where buyers visit, they are precisely classified and numbered. For example, Dorcus grandis is in the first class, Lao Dorcus curvidens is in the second class, and Dorcus antaeus is in the third class. Obviously beetles in the first class are valued and bigger ones are sold at a higher price.

Shidar was wearing a worn-out T-shirt, but I saw something glittering around his neck. It was a gold necklace. He bought it for 18,000 yen that he got by selling a stag beetle last year. The stag beetle he caught was in the first class and it was as big as 8.5cm. If he catches 40 stag beetles of the second or third class in a day, they will not bring him more than 2,000 yen in all. But he said with a twinkle in his eyes, “It’s very profitable. I’m saving money to buy a motorbike.” He walks to the wood and back for four hours to catch stag beetles. He said he wanted to use the motorbike to go there.

Piles of dollar bills

I saw a man in a purple sleeveless shirt drinking liquor in broad daylight in a restaurant at the entrance of the village. This red-faced man is the assistant chief of the village Bun Pen. And he is “the boss.” He sells stag beetles captured by the farmers including Shidar to Japanese buyers. According to him three Japanese buyers already came this year. At the inner part of the restaurant, which his wife ran, there were stag beetles in a plastic case labeled “Sample.” Beside it there was a box stuffed with wads of bills.

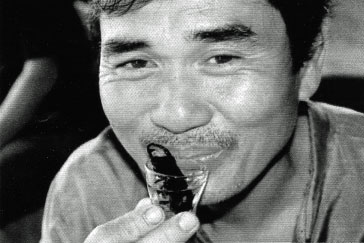

“Dorcus grandis is now sold out. This one is cheep because it’s in the third class. It is 2,500 yen,” he said and picked up a 7.5cm Dorcus antaeus. Taking Shidar’s story into consideration, Bun Pen must earn a lot. He didn’t tell me how much he earns a year, but he said, “A Japanese bought a thousand of stag beetles at once, showing off his money. We had piles of dollar bills.” It seemed he couldn’t stop chuckling.

When he drank up liquor in a plastic bottle of cola, he took a new bottle of liquor out of cupboard delightedly. “This is special liquor that I don’t serve to a customer,” he said, holding a bottle cautiously. The bottle is filled with more than 50 black beetles. He said it was stag-beetle liquor. “There are some defective beetles like legless. They are not salable, so I put them alive into liquor.” He took a sip of the liquor with relish and offered me a sip. He said it was good for AIDS and also made a man vigorous.

The number of stag-beetle traders has increased underground

Stag-beetle brokers like Bun Pen call Dorcus grandis “Black Buffalo’” in secret language. I visited a broker, Way Saopen, in Phon Savanh City to see a Buffalo, which I couldn’t see at Bun Pen’s place. Way Saopen deals in more than 100 stag beetles a year and earns a yearly income of a little less than 200, 000. There was a 6.5cm-long Dorcus grandis priced at over 7,000 yen. He said that the biggest Dorcus grandis he had ever dealt in was 8.5cm long same size as Shidar caught, and that it was sold for 30,000 yen.

It seemed that the whole city were on the watch for an opportunity to go into the stag-beetle business. A middle-aged woman who ran a travel agency bought three stag beetles one week ago. She said, “Tourists may want them as a souvenir.” When I asked her name, she refused to give me her name, saying that she didn’t want people to think that selling stag beetles was her main business. But the true reason for her refusal was that dealing in stag beetles was presently prohibited in Laos. Three years ago Japanese buyers went about purchasing stag beetles by the thousand at Coo Village, and the farmers were busily engaged in catching stag beetles. But most of them didn’t know what kind of trees “tree bugs” liked, let alone its ecology. They cut down the trees in the woods one after another. Worrying about the loss of forest resources, the authorities decided to apply the forest law. They confiscated stag beetles together with the vehicles and forbade the buyers re-entry into the country.

A gap between the habitat and the importing country

I thought if the government notified people widely how to capture stag beetles and impose an export tax instead of forbidding capture itself, a new industry would arise in Laos, one of the poorest countries. I asked the Xieng Khouang office of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry about the feasibility. However, the assistant chief of the office Kanpon Udomsuek answered me curtly, “If a trader applies under the condition that they should not cut down a tree, we will consider it. But so far, no one has filed an application.”

Now the ban was removed, but you need a scientific warrant issued by the exporting country to bring a stag beetle into Japan. However, I‘m told the Lao government has not issued a warrant and it will not either from now on.

Then, all Dorcus grandis that are on sale in Japan should be smuggled. Consequently Japanese dealers price Dorcus grandis the highest. I made inquiries at a store specialized in stag beetles. They said that the market price of a Dorcus grandis under 7cm long is about 50,000 yen and that of a Dorcus grandis over 8cm long is more than 100,000 yen. The price of a Dorcus grandis over 8.5cm long is 150,000 yen at least.

One year has passed since the Plant Protection Law came into force. The impoverished villages in Southeast Asia, where not a tourist had come, have changed completely by the advent of Japanese buyers. There was some expectation that the amendment of the Plant Protection Law would make the stag-beetle business honest and an insect industry would arise in the countries with tropical rain forests such as Laos. But the materialization of the expectation looks bleak. The circumstances of the stag beetle’s habitat should be taken into consideration once more.