Thailand Trip for HeartsSeptember 2003

Children who have no house registration

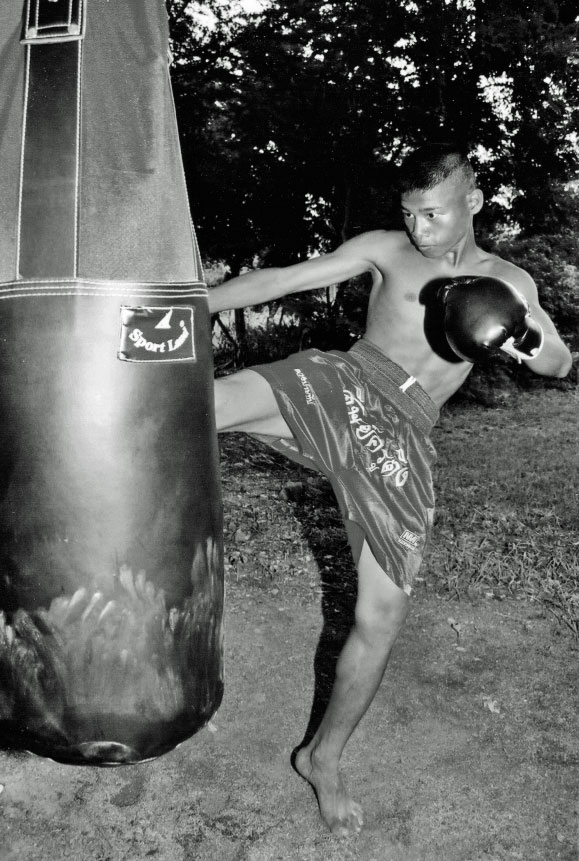

Rah is a 15-year-old boy. He wants to be a Muay Thai boxer. He doesn’t know his parents’ names, let alone when and where he was born. He had been forced to go begging in Bangkok with his sister Nahn (14) since early childhood. When their earnings were less than 500 baht (about 1,500 yen), his boss pushed a cigarette light on his body and hit his sister on her nose. His scars of burns disappeared but the constant hits made his sister’s nose flatten.

Five years ago Rah and his sister came to the New Life Project in Kanchanaburi, which is run by the Duang Prateep Foundation (DPF). In this institution 44 boys and girls ranging from 3 years old to 23 years old live together. They were treated cruelly or deserted by their parents like Rah. Rah and his sister go to school in a village together with the other children in the institution, but before they were taken into protective custody they had never attended school, so that both of them are now in the fifth grade. They, however, will not be able to go on to junior high school because they don’t have a house registration. A child who has no house registration can be accepted at an elementary school in a village, but not at a school of higher grade. Even now Rah has to borrow his classmate’s name to take part in a Muay Thai match.

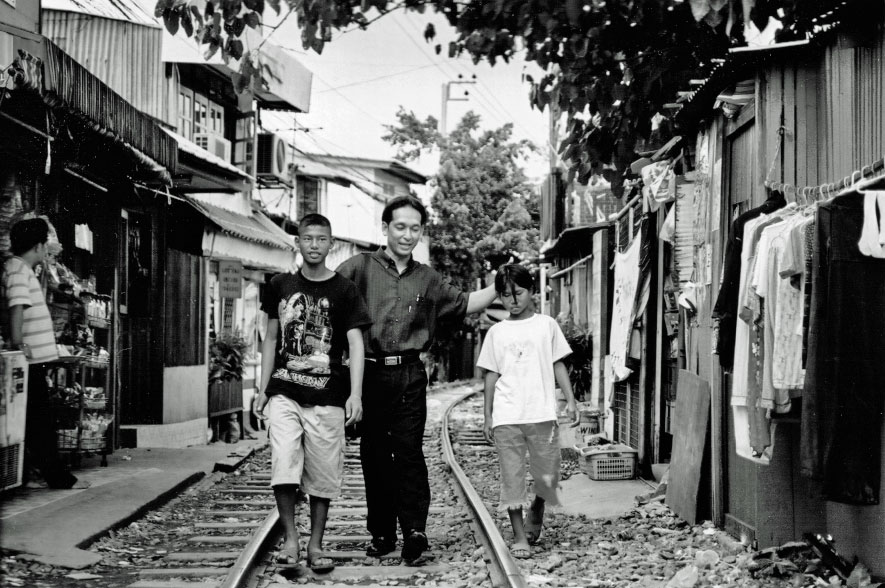

A social worker Montien (34) decided to take them to Bangkok’s largest slum Klong Toey Slum with about 100,000 residents, where Rah and his sister were taken into protective custody. They need to find a witness whose testimony is required to get a house registration.

The DPF, a pioneer of Thai NGOs, originated from ‘One Baht per Day School’. The Foundation Secretary General Prateep Ungsongtham Hata, who was born and grew up in Klong Toey Slum, opened it for the children in the slum who could not go to school when she was a student. She received Magsaysay Award at the age of 26 and set up the foundation with the prize money. Since then she has worked not only on education for the children of poor families but also on the eradication of drugs and AIDS for about 25 years.

Study tour to slums

A Japanese group came to the slum to study such NGO activities. The study tour was planed by a Japanese professor. Before this 12 study tours were made. This time eight working adults and eight students joined the tour. First they visited the DPF Kindergarten. After they were greeted by children, they took a lecture on the history and present state of slums from DPF Secretary General Prateep Ungsongtham as well as on the New Life Project where Rah and his sister lived. They were listening to her attentively and taking notes. The lecture seemed to students to be a lesson and to working adults to be a meeting.

DPF Secretary General Prateep Ungsongtham said, “Even if Rah and his sister were born in Cambodia or Myanmar, we should give them educations. When they grow up into good persons, they will be useful for our society.

After the Japanese tour group got some guidance, they went to the slum. The sight of the slum shocked the Japanese students. In Japan there had been shanties standing along a river or a railroad track till the 1960s, but today’s Japanese students have never seen such a sight. Forming a line, the tour group followed the guide of the Foundation into the maze of alleys. Since this area was originally wetlands, the many paths were covered with water because of yesterday’s rain. The rubbish that had been thrown away over a period of dozens of years was floating all over the surface. Adults who have worked without receiving an adequate elementary school education get only low wages and have trouble supporting their family. There seems no way to come out of poverty. As the result their children have to bear a burden.

The orphans are looking for a witness

While the Japanese tour group was looking around the slum, Montien was asking around in the slum with Rah and Nahn in search of a witness. He was worrying that the children’s trauma might be stirred up and they might be depressed. He held Rah and Nahn’s shoulders by turns. He told them that they could stop anytime if they wanted to.

“Do you recognize these children?” “I’m afraid not. Don’t they remember anything about themselves?” “No, they don’t.” In Japan, when an orphan is taken into protective custody, the head of a community where the orphan has been found names him/her, decides his/her legal domicile and makes his/her name entered in the registry. In Taiwan, however, parents’ names and address are required to have a house registration and if parents are missing a witness or evidence of the birth like a medical record is required. It is very difficult for an orphan to get a house registration in this country, where illegal immigration from the neighbor countries is a big issue. If the decision about a house registration is entrusted to the head of a community on the grounds that human rights are the most important, a corruption case where a house registration is sold with money may occur. In slums and along the border there are at least one million stateless people.

“Please let me know when someone comes to ask about these children,” Montien said and went to another house. They made a house-to-house visit, asking for some information. In one of the houses they visited, they met a blind woman. Montien said, “We are looking for the place where these children lived. “Whose house? Boi’s?” She drew Rah close to her and touched him. “No. Rah’s. He is a boy the DPF is taking care of.” “Are you a friend of Boi’s, Rah?” “Yes, I am,” said Rah, who had never said a word so far. “Sorry, but I don’t know where your house is.” Montien decided to stop the search when he saw clouds on the faces of the children.

“This case is very difficult. There is no clue to find out where they were born. We are totally at a loss. But if we can’t find …,” Montien signed. The three, however, took heart and went to the police station in Klong Toey Port. Five years ago, when Rah and his sister were sleeping on the floor of this police station, they were found and taken into protective custody.

“Why, it’s you! Long time no see,” said a police officer when he saw Rah. “Does he go to school?” “Yes, he does, and he does well at school.” Montien seemed to be proud of him. “You named these kids, didn’t you? I remember it.” “Yes, that’s right. If I remember right, they were lying behind that air conditioner.” Pointing toward the air conditioner, the police officer seemed to be recalling the looks of them at that time. He said that the children had been forced to go begging and they had been very backward in speech. When he found them they couldn’t tell even their names.

The oil palm project was a smash hit

While Montien and the children were searching information, the Japanese tour group was at the New Life Project after touring the slum. The number of visitors coming here is about one thousand a year at its peak in April and August. 80 % of them are Japanese and most of them come in a group by bus. This institution opened in 1993 with the aim of rehabilitating girls on drugs. Under the worldwide recession the DPF set up a project for planting oil palms last year so that it can be independent financially. “A 25-year-old man should be independent. So should the DPF.” DPF Secretary General Prateep Ungsongtham explained why the DPF set up the oil palm project 25 years after it was founded.

In this project, the DPF solicits for contributions from supporters. A contribution is 5,000 yen per a nursery oil palm tree. They are planning to plant 4,400 oil palm trees on the land of 320,000 square meters, and then sell the products made from the oil palms ten years later. They think that revenues generated from the trees will cover 65 % of the DPF’s annual operating expenses of about 8.75 million yen. DPF Secretary General Prateep Ungsongtham came to Japan early in June for a campaign to raise contributions and it took less than two months before the goal was achieved. The oil from oil palm tree can be made into soap, low-pollution fuel and so on. The oil palm tree, a tropical plant, grows so fast as to overlap the growth of a child. The offer that a supporter’s name would be attached on an oil palm tree they donated seemed to be another key to the success.

Rolls of drums and shouts of joy came on from the hall of the New Life Project. Both of the Japanese tour group and the children could not make themselves understood in language, so they tried to get to know each other by singing songs and playing games together. All the children had terrible experiences in the past like a girl who had been a victim of child prostitution, but I couldn’t see any worry in their smiling faces. Rah said he wanted to be a boxer, while his sister Nahn said, “I want to be a masseuse, because I like to take care of old people.” When I asked what they thought of Japanese visitors, both of them said, “They are very kind to give us a lot of support.”

The reason to come at their own expense

All of the Japanese study tour members came at their own expense, spending their holidays away from work or school. The New Life Project Manager Prakhong said, “Maybe they want to ascertain their problems to be trivial by looking at the conditions of the children here. That’s why they come, I think.”

The Japanese treated the children to Japanese food like yakitori (grilled chicken on skewers) and fine noodles, and sang Japanese children’s songs for the children. The Japanese tour group chose to spend their holiday in visiting Thai children in slums or rural districts, not in visiting a hot-spring resort. They must have thought that they could gain something from the tour, so that they joined it, I presume. This presumption was proved to be right when the tour members made farewell speeches at a farewell party held on the last day of the three-day stay at the institution. The first speaker was a music teacher. “I don’t know when I’ll be able to come again, but I will someday, maybe when you are grown-up,” she said, being choked with tears. It took her more than one minute to deliver this brief speech. The children looked astonished to see her crying, wondering why she was crying.

Masahiro Furukawa (52), a teacher of a public junior high school, said, “My enthusiasm for education was almost deadened. But when I saw the people working here devotedly in behalf of slums and the Project, I regained my motivation. I told the students in our tour group that they should take more interest in Japanese children. There are many children who have stopped going to school, become delinquent, and given up going on to the next stage of education. But that’s what we teachers also have to pay heed to.” He also seemed to be deeply moved.

Tae Murakami (29), who works for a university, also made a speech with her eyes moist. Holding a boy she is sponsoring on her laps, she said, “I couldn’t compose my mind in Japan because of the stress of work. But my mind was eased by the children’s smiles here. However, when I heard their terrible past, I felt ashamed of myself. This trip put heart into me.”

The study tour group comes all the way from Japan at their own expense, spending their holidays. A person living in Japan can easily understand that they want to see the children who are not discouraged by adversity for catharsis. But those Japanese behaviors seemed mysterious to Thai children who didn’t live in adverse circumstances from choice. Nevertheless, this study tour yielded a very good result that the Japanese tour group and Thai children took more interested in each other.