Cambodia Airfield of the Japanese ArmyApril 2005

60 years after the war

It must be over a body temperature. The hottest season comes three months earlier in Cambodia than in Japan. As I was driving in Kampong Chhnang Province, I saw the field of sugar cane on the ridges stretch to the horizon, and then a vast vacant field came in sight suddenly. The field was paved with asphalt, and in the middle of the field blocks were buried in line. It is the ruins of an airfield built by the Japanese Army. The field is covered with earth and weeds are growing out of the cracks in the pavement, but still a small plane seems able to take off and land even now 60 years after the war. The Japanese Army landed in French-owned Indochina at the end of July in 1941 and they built or requisitioned 14 airfields including this airfield to establish a bridgehead for India, the south of China, Malaya and Philippine.

Now this place has become a post of the first brigade of Royal Cambodian Army. On the parade ground beside the runway, about two thousand soldiers ranging from 22 to 50 years old were having a rehearsal for a review of the troops. There were no tanks or missiles. They will probably demonstrate how to knock down a sentry carrying a gun with bare hands. Since Cambodia had been in a state of civil war over a period of nearly 30 years, the demonstration will be given on the assumption that they might combat closely against guerillas.

Spending most of life time in fighting a war

The brigade commander Major General Prung Penh (44) was born in Kandal Province and volunteered for military service at the age of 18. His mother and sister were killed under the Pol Pot regime, and he fled to Vietnam, where he was put in jail and questioned on suspicion of espionage for a month. But after his suspicion was cleared, he joined the Vietnamese Army and made a triumphant return to Cambodia. He was one of the heroes who ran the Pol Pot group to the Thai border and liberated the country.

Showing me around the airfield, Major General Penh said, “When I was a child, air raids started and we went through military drills at school. I spent most of my life in fighting a war.” However, soldiers in this base spend peaceful days growing vegetables and planting fruit trees. Since their enemies have gone away in 1998, to help farm villages have been their regular duties. They help farmers with their rice planting. Last year they were sent out with pumps to help the farmers in drought-stricken areas. “Even a former soldier of Pol Pot says ‘No more war.’ To be frank with you I don’t want to hear any news about Iraq. The only people that don’t know what a war is like want to fight a war.”

The issue of a war is decided by transportation capacity of soldiers and goods, so that the former Japanese Army built an airfield here. To win a victory the enemy tries to block a supply route and cut off the retreat before they attack. The invading troops have to fight not only to invade but also to secure the safety and to clear the retreat. But it is always defenseless citizens that suffer damage. Major General who had fought in the front line until 1998 often faced such reality.

The camp of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces lies in ruins

“This area used to be a Japanese quarter, didn’t it? My father told me so,” said Song Sari (13), picking tamarind fruit at the ruins in a village of Takeo Province. He doesn’t remember anything about UNTAC. This is the place where Japanese Self-Defense Forces was sent out at the end of September 1992 for the first time in half a century after the Japanese Army invaded. In a prefabricated building that was used as a headquarters and canteen by an installation battalion, a guard is taking a nap. The room is very quiet. The great silence reigns over the room. There is nothing except a very big bathtub covered with dust. Without an air-conditioner, it is unbearably hot inside.

The Japanese Self-Defense Forces gave this building to Takeo Province when they withdrew, because they thought dismantling and transporting it would cost a great deal. The building was used as a job training center for three years after. There the local people could learn how to sew or how to repair a motor bike. But the center was closed ten years ago because the Cambodia government couldn’t bear the labor and maintenance costs. A stack of textbooks and the whiteboard on which a timetable was written tells that the plan was frustrated.

In those days, the village in the neighborhood of the camp was very active due to Hinomaru boom. One of the farmers opened a yakitori bar for the members of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces, and children peddled canned beer and boiled eggs. Everyone in the village says, “Why did they go back to Japan?” I talked with one of the villagers, whose name is Sam Rot (24). She invited some members of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces to dinner at her house. She even guided them to the Vietnamese border on her holiday.

“At that time I was 12 years old, and I was working at a beer shop. Mr. Soften came to the shop. He was, so to speak, my brother.” She showed me his photo and some airmail letters from him. The letters, whose ripped folds were fixed with cellulose tape, were sent to her in six years after he went back to Japan. “I had waited for him for ten years, but he didn’t come. So I got married.” The villagers gathering around her burst into laugh. It is not altogether a joke, because in this country it is not unusual that a girl gets married at the age of 15 or 16.

The area of the ruins of the camp is as many as 23 hectares, and about a half of the land, on which the villagers had grown cucumbers, watermelons and cassava, was offered to the Japanese Self-Defense Forces for nothing by the villagers. Even after the Japanese Self-Defense Forces withdrew and the job training center was closed, they are not allowed to farm. So the villagers still have to buy vegetables at the market. More ironically, this land also used to be an airfield of the Japanese Army.

The Japanese people who came by orders

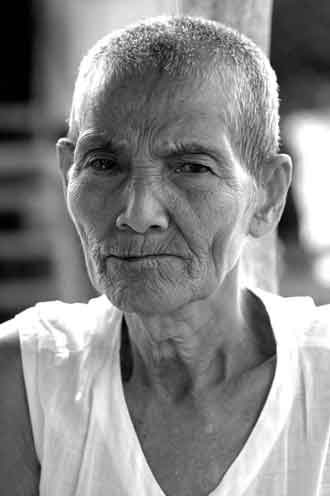

There is an old man who was forced into service by the Japanese Army to build an airfield. Few people know about that time in this country, because the average life span of the Cambodian is 56.7 years old. When I visited Nutu Suck (80), who even survived the massacre by Pol Pot, he was bathing in water in the yard.

“I was told that the Japanese Army only got transit permission from the French Army, but hundreds of Japanese soldiers on vehicles and horses came to the village and started building an airfield.” Suck said that he could not erase some Japanese words from his memory. When Japanese soldiers saw a villager working slow, they shouted to him in Japanese, “Yokunai! (Bad!).”

They divided the villagers into two groups and made them work in two shifts of 15 days, and they compelled hard labor. The villagers were brought out to work with their cart cows. Farmers with a cart cow were paid five riel a day, and those without a cart cow were paid 1.2 riel. They had to clear the dense forest and pave the grounds with stones that they brought from the craggy place about eight kilometers away. Although they had a lot of complaints about being treated badly, they could not defy the soldiers because they had their gun at the ready. Hundreds of farmers were brought to work from other provinces, and even elephants were substituted for construction machines. In such poor surroundings cholera broke out and many people died. But there has been no lawsuit and no cenotaph was erected. If the witness Suck passed away, the fact of this tragedy might be concealed as if it had never happened.

The reason that the Japanese people could work Cambodian people so hard at construction heartlessly was that they came here as a soldier or an employee under the orders of the Army or his employer, not as an individual with willingness. To put it in the other way around, they didn’t come because they liked the people or natural features of Cambodia.

Mr. Hara’s wife

I heard there was a former Japanese soldier’s wife in Kampong Speu Province, so I visited her. Meng Pang (79) lives in front of Udong Temple in a temple town. She asked me in Japanese, “Do you want to have a meal?” I was surprised at her fluent Japanese. She was tonsured like a nun. She was tall and had a straight back and clearly-marked features. Suck had told me about her. “She was so beautiful. She was the admiration of men.” That was well said.

“We got married when Hara was 33 and I was 23. Our wedding was held in grand style. About 200 Japanese soldiers and about 100 villagers came to our wedding. Hara was about 170 cm tall, plump and fair-skinned. One day in the rainy season of 1943 he told her parents that he wanted to marry her. With their approval, he gave betrothal money of 700 riel equivalent to an annual income of a Cambodian laborer.

Judging from his age, freedom of activities and great skill in car maintenance, I reckon he was a noncommissioned officer or junior officer of the engineering troops or he belonged to the troops which dealt with vehicles. He gave their house in the village to his wife’s parents and they moved into the new house in Phnom Penh. He hired a Chinese cook and housemaids and took up residence in the best district of the city, where the headquarters of United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) lead by Yasushi Akashi was situated. The command post of the Japanese Army was in Phnom Penh before the Second World War ended. Pang said, “He bought me new dresses and took me along on a business trip down to the country. He often asked me to sit on his laps. I felt so embarrassed. Then he said there was nothing embarrassing because we are a married couple.” He never used violence or yelled. He was very kind-hearted.

When the Japanese Army withdrew to Japan after the war ended, Mr. Hara went back to Udong where Pang’s parents lived. In October 1945 the French Army brought Phnom Penh under its control and colonized the country again. Mr. Hara was taken away by the French Army and his whereabouts has been unknown. An interpreter told Pang that he had been taken to Saigon, and that’s all she was informed.

At that time they were separated, Pang was pregnant with Hara’s child, but she had a miscarriage. Two sisters of hers died of illness in the Sihanouk period; her parents died of huger and her brother was killed in the Pol Pot period. Pang came back to Udong with an orphaned relative 20 years ago. She had lived by assisting farmers in their rice farming, but for the past four or five years she has been suffering hypertension and stayed at home. She said, “If I could see Hara again, I would like to tell him I had been dying to see him for a long time. But I don’t think he is alive. If he was alive, he would come to see me without fail.” Mr. Hara, who tried to stay in Cambodia unlike many other Japanese people, must have loved a Cambodian woman Pang and her country Cambodia very much.

The summer after 60 years

Phnom Penh, where Pang lived a newly-married life 60 years ago, is far from being affluent. I had scarcely gone out a cafeteria when beggars with babies in their arms gathered around me, and I saw boys in bare feet collecting empty cans. Cambodia was once a French possession and invaded by Japan.

After the war Pol Pot carried out the physiocratic policy frantically to reduce the extremely wide differentials between Cambodia and the great powers. The domestic warfare against Pol Pot was fueled by the Cold War between the East and the West. The rice in aid sent by Japan to help Cambodian citizens went to guerillas. According to the 2002 survey by the United Nations Development Organization, Cambodia ranked as the worst country in Asia on the lists of under-5 mortality rate (U5MR) and GNP per capita; U5MR was 135 and GNP per capita was 260 US dollars. What would you say to going to Cambodia in the summer 60 years after the war and pondering the meaning of the oversea dispatch of the Self-Defense Forces with arms and the reason why they cannot go without arms.