Burma(Myanmer) The Last BulletJune 1991

ON BOTH BANKS OF THE RIVER MOEI

BURMA VS. MYANMAR

“Two ministers of rival government return to Rangoon.” I was surprised at this headline in the Thai newspaper. I was about to leave that very morning to pay a call at their Prime Minister’s Office in Manerplaw, Burma.

The Moei is an unusual river. Beginning in Tak Province, Thailand, it flows north, away from the sea. Manerplaw is about 150 kilometers downstream from Maesot, on the opposite bank. From the end of a paved Thai road, it would be easy to go by boat, but Myanmar troops block the way. Only my mind can hasten to the landing place of Karen liberated area, past jungle so dense that we can penetrate it only by elephant. Six hours from Maesot I at last reach “Burma” and set my watch back half an hour.

The Minister of Information, Mr. Hla Pe (43), one of the eight elected MP’s who founded the coalition government on 18th December of last year, adamantly denied that the two ministers had “surrendered,” as the military government announced. “They were kidnapped!” he swore. “It’s not a rumor because their escorts have in formed us directly.” Mr. Aumnat (37), a reporter for the Thai paper, the Nation, offered an insight: “One of the two was the ninth member who came out after the government was set up. So that man could have been bought off by Military Intelligence.”

The Minister of Information continued,”The modern history of Burma is riddled with lies. Inside Burma, SLORC, (the State Law and Order Restoration Council) points guns at us. We don’t have an iota of freedom of expression or of the press. More than a hundred MP’s have been arrested by now. They had already captured 84, though the junta announced only 21, by the time I left. One of the most important missions of the coalition government is to bring out the truth from the inside.”

Last October Japan’s newspapers reported “Myanmar Cracks Down on Dissident Monks in Mandalay.” I learned the real story behind this from Ven. Vimala (fictitious name), a 22-year-old monk from Mandalay who had fled to the border to escape arrest. “The united monks tried to offer the monasteries to NLD* as a secret as sembly hall for forming the parallel government,” he told me matter-of-factly. ” For our part we tried to hide it from SLORC by holding the third anniversary for the victims of the armed suppression.”

“In Mandalay, their action was just suicidal,” declared Bo Mya (64) Chairman of the Democratic Alliance of Burma (DAB), a coalition of 21 anti-junta organizations. “In fact, I invited the MP’s here. Now we are fighting so they may come into power although we have fought for our own independence for more than forty years. We are fighting for them because they acknowledge our–the minorities–rights.” As General of the Karen National Liberation Army, the strongest guerrilla band, Bo Mya has put their future under the charge of the new government, as well.

I also talked with Kaine Soe (44), General Secretary of the National Democratic Front (NDF). “My parents told me that they’d been terrified of torture by Japan’s soldiers during the war,” he said, “but Japanese civilians have worked hard and loved peace ever since those harsh days. If Japan actually espouses democracy, we expect she will recognize this government supported by the people. Otherwise, if Japan continues to be the junta’s biggest donor, she will repeat the same mistake as she did 49 years ago, won’t she?”

In the United Nation General Assembly last December, made the motion to shelve the draft resolution against Myanmar. The motion was carried.

* The National League for Democracy, who won more than 80 percent of the seats.

“OUR CHOICE WAS RIGHT”

“There’s no easy revolution!” exclaimed Kyaw Thu (fictitious name) (22), ABSDF (All Burma Students’ Democratic Front) camp-chairman, when asked about the five thousand students who have surrendered. “We love freedom, so we think it was also their freedom of choice.” Then he firmly pressed his lips together and said no more.

Shortly after the military coup on September 18, 1988, more than seven thousand students suddenly found themselves fugitives in the jungle along the Thai border. However, malnourished and unaccustomed to the harshness of the jungle, which swarms with mosquitoes in rainy season and changes more than 20’C in a single day in dry season, many fell victim to malaria, hepatitis, dysentery, and other virulent diseases. Besides those difficulties, the junta made vicious attacks on the their encampments during their first dry season. Many students “surrendered” by retracing their steps home, while others accepted the Thai-Myanmar repatriation offer.

At present, there are 2,739 students staying in fifteen camps along the Thai border. Including those grouped on the Chinese and Bangladesh frontiers, more than five thousand Burmese students continue to oppose the junta. Students from two ones of the three camps that I visited two years earlier were forced to evacuate when their encampments were overrun. The only casualties, however, were three students who died of malaria. The chairman told me that none were killed in the fighting.

The students rejoiced at the opposition’s victory in the general election, but, after witnessing the sacrifice of their comrades, their joy was short-lived. The junta defied the most basic rules of politics in refusing to transfer power to the winners. As the students were commemorating their third New Year’s in the jungle, three MP’s of the new coalition government, a milestone in Burmese democracy, visited their camp. “We all cried for joy that night,” said Kyaw Thu,”because we knew for sure that our choice had been right.” He compared the new government to his “last bullet.”

Yan Aung (fictitious name) (28), an ABSDF commander had just come back from a reconnoitering mission about 50 kilometers west of the front line. “All the villagers helped us by giving food, reporting about the enemy, and hiding us,”he said. Speculating on the situation of government troops, he added,”This year the junta must need more soldiers just to watch out for uprisings inside Burma.”

ABSDF cooperates with the National Democratic Front (NDF), which is the armed force of eleven minority groups, in the struggle against the junta. Together with their families and noncombatants, they total about 60 percent of Myanmar’s whole population of 41 million, according to Kaine Soe, the NDF leader. But all camps are reinforcing trenches at the frightening report that government pilots are training with the jet fighters the junta bought from China last year.

The River Salween flows through their fatherland to the Andaman Sea.

The students’ Salween Camp is near the point where the Moei joins the Salween.

This mighty river carries the students’ determination as if flows to Myanmar.

THE TWO CARDS

In a restaurant in the border town of Maesot, Tak Province, a senior staff member of an American NGO (Non-Governmental Organization) was briefing two new workers about the refugee camps. Although I listened carefully, I could not hear the words,”Burma”or “Burmese” because he deliberately substituted “There” and “They” each time.

After the hijack last November, the Thai government banned all relief for Myanmar refugees, even from UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). Although the government has threatened to deport anyone aiding the students, I saw some volunteers holding classes in English, political science, horticulture, and economics at the jungle University in Manerplaw and at branches in the camps. With only tourist visas, they are voluntarily teaching as private individuals. There were three from the U.S., two from Canada. and one from the U.K., but none from Japan.

One 23-year-old man from California had just outlined “basic human rights” on the blackboard in front of his Burmese students, some of whom were older than he. “There should be many more Americans who oppose the Gulf War,” he mused thoughtfully,”but it’s hard to fight against ‘Righteousness.’ I’m not really teaching, but I am learning from them what freedom is.”

In the Burmese quarter of Maesot, I had milk tea Burmese style with Bo Ni (34), a worker who has been in Thailand for twenty years. “A Burmese worker’s wage is about half of a Thai’s, but the Thai manager turns aside investigations by putting something in the authorities’ hands,” he said frankly. “That’s the give-and-take of the situation.” Despite the Thai government’s announced policy to strengthen control of illegal entrants and the plan for detention camps at the end of the year, Bo Ni said that nothing had changed around him.

Cynthia Maung is a 31-year-old Burmese doctor. She declares that she is fighting the junta by treating with no charge any of her compatriots who cross the border. “One family was so poor,”she explained,”that they didn’t come to my hospital until they all had acute tuberculosis. In Burma there’s no social welfare at all. This is a fundamental problem doctors cannot do anything about. First of all we need a revolution.”

Although the local commissioner of Maesot is well-aware of the existence of “Dr. Cynthia’s Clinic,” no investigation has disturbed this sanctuary.

“Don’t you think it’s like HONNE and TATEMAE?”asked Dr. Nakarin Mektrairat (33), assistant professor of the Political Science Department, Tamasaht University. “In conducting its foreign policy, Thailand has always played with two cards. Thailand shares land borders with four countries. To the outside world we show one black and white card, demonstrating that we are a sovereign nation, but to each neighbor, the card is subtly iridescent. Although such an approach is very Asian, Japan’s diplomacy has now become rigid like that of the West,” he concluded.

Out of the blue, the Thai military staged a coup d’etant on February 23. In the United Nations Buildings two weeks later, a large crowd of longyi-clad men and women sat on the marble floor of the lobby. They were Burmese who, having fled their homeland, wished to be recognized as ‘persons of concern’ to UNHCR.

Only 20% of them can fulfill UNHCR’s stringent conditions, but those who qualify receive a maximum of B3,000 per month, despite the Thai authorities’ threats. In the eyes of the Thai coup leaders, they are all merely illegal immigrants who should be put in the Detention Center.

In a lecture in Osaka on March 3, Bertil Lintner (38), Burma correspondent for the Far Eastern Economic Review, expressed concern about the coup’s effect. “Although the Thai Foreign Ministry has been sympathetic to the pro-democracy Burmese,” he said, “the Thai military leaders are on intimate terms with the heads of the Myanmer junta. The Burmese army could even occupy Manerplaw if Thailand would allow them to enter from its side of the border. The President of the Coalition Government, Dr. Sein Win, was looking for a third country which would shelter his government-in-exile.”

MILITARY MISMANAGEMENT?

The sound of shelling from the opposite bank of the River Moei echoed in the grotesque scene. Only blackened pillars shone like used charcoal standing in the grass. I could not believe this was the same market in Wang Kaew, half an hour south from Maesot, where two years before I had sat drinking tea. In February last year, Saw Maung’s troops crossed the river into Thailand and burned the market to the ground.

“Every night I hear government troops firing although there’s no combat anymore,” said Chatri C. Mukol (48), a famous film director and member of the Thai Royal Family, who is shooting a film on location in Mae Thawa, which used to have the biggest market in Tak Province. “They must be shooting at the ghosts of Karen soldiers killed in the Battle of Mae Thawa.” Director Mukol is working on a war film in the middle of what was literally a “ghost town.”

According to the junta the black market is a source of revenue and an open border for the dissidents. That’s why it is an important target. Ironically, theb population in the impoverished minorities’ refugees villages near those closed markets has almost doubled. Along another border area overrun by government troops, a little northwest of Bangkok, the 251 students of the Three Pagoda Pass camps have temporarily sought refuge on the Thai side, and more than five thousand refugees not only minorities but also Burmans, have escaped to Kancha-naburi Province. There are estimated to be over fifty thousand refugees from Burma in more than fifteen different locations along the Thai border.

“Our exports decreased by half!” complained Niyom Watratpang (45), chairman of the Tak Chamber of Commerce and Industry. “Until two years ago, our trade amounted to a billion baht (B1=\6) a year. It seems that the business which we have always carried out with the Burmese people has gotten all mixed up with politics.” Desperate to find a solution, he has just decided to run for a seat in the Parliament. The Myanmar government unilaterally closed the border, stopping all trade, after a bomb exploded in Myawadee, opposite Maesot, the end of last November, declaring that it was the work of dissidents tacitly protected by Thailand.

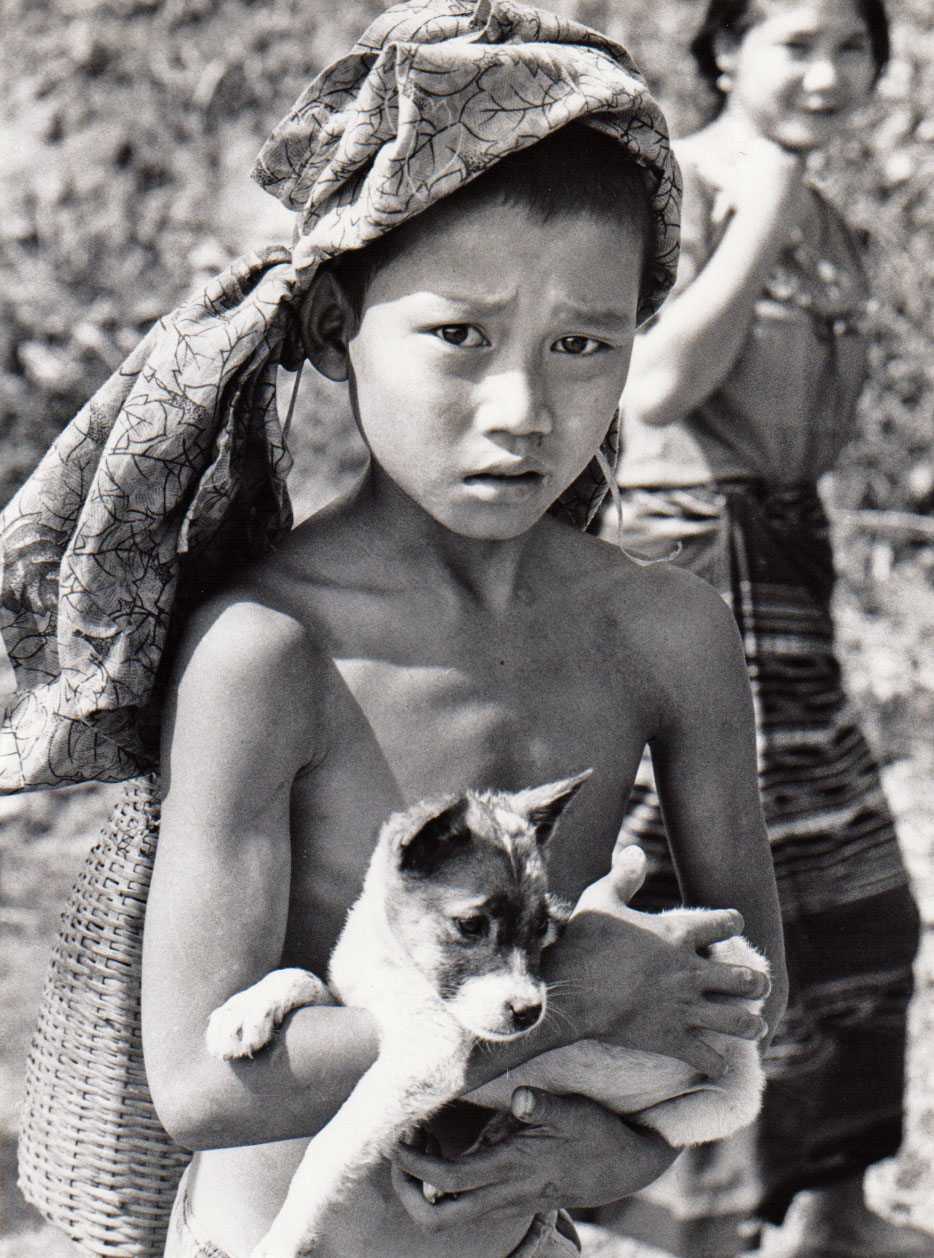

A refugee who had just arrived from Mergui reported that in that port town in southern Myanmar, primary-school-aged children from a long queue from early morning at the employment office. The lucky ones are able to get a job that pays a pitiful 15 kyats (about 45 yen at the actual rate) for laboring all day in a dry-fish factory. Most of the children, however, cannot get any work at all.

It was near there last year on December 29, that Burmese students hijacked a Thai trawler. A few months earlier, when two students had hijacked an airplane from Bangkok, they were able to hold a press conference at Calcutta Airport.

This time, however, the students were cornered and blew up the trawler six days later. “Their aim was to appeal to the world over what the junta is doing when it sells fishing rights to foreign fishery companies,”explained Dr. Thaung Htun,Secretary of Foreign Affairs of the Central Committee of ABSDF, defending the students. “Burmese fishermen can no longer make a living in their own waters. The students had no intention at first of sinking the trawler, but the Thai captain radioed for help and the Myanmar Navy was closing in on them, so they had to do something to prevent our real aim from being completely silenced and to avoid being called mere pirates by the government. No lives were lost: the students dropped off the crew and even the hi-tech equipment on an island before blowing up the boat. “Nevertheless, not a word about their appeal nor anything about the incident itself appeared in Japanese papers.

Under the tropical sun, the Moei riverbed glitters as if strewn with diamonds because of the millions of chips of mica scattered there and tin veins, exposed by the erosion, shine a bright azure on the steep riverbanks. This valley is also a rich gem field. Seated next to me in a motorboat, a 29-year-old mining engineer sharply criticized the Myanmar government’s senseless exploitation of the mine where he had worked. “The coalition government,” he continued,”will try to attract foreign companies soon, so we’ll be able to….” Even as he spun his fantasies for the future, the military government was holding a gem auction in Rangoon for buyers from Japan, Germany, Italy, and elsewhere. According Kyodo News Service, they signed contracts worth US $22 million.

On the way back from Manerplaw, I finally managed to pass ten huge logging trucks crawling along the highway under cloak of darkness. They carried Burmese teak logs to be exported through Thailand. “Burma had strict laws to prevent deforestation but the junta is wantonly sacrificing our natural wealth to get war funds,” Bo Hla Tint (33), Minister of Mining and Energy Resources in the Coalition Government had told me, condemning the military’s mismanagement.

“Congratulations to the people of the Union of Myanmar on the Occasion of the 43rd Anniversary of Their Independence Day… Japan-Myanmar Cultural, Economic & Friendship Association,”proclaimed one ad. “New incentives for investors. There is an unequivocal state guarantee against nationalization and expropriation,” promised the headline of a long article. Such love letters were exchanged in one of Japan’s English language newspapers. To preserve the newspaper’s honor, the editor had added at the bottom, “This article was provided by the Embassy of Myanmar in Tokyo.”

HOPE

The Burmese students at the border have called the Coalition Government their “last bullet.” “Then Mrs. Ogata was truly ‘the last hope’ for the people inside Burma,” said one of the two students I had met two years before. This time we were meeting at a bustling spot in Bangkok. The two are no longer camp leaders; now they are active as spies for ABSDF’s underground section.

The last assignment undertaken by Ye Htut (fictitious name) (25) was to coordinate pro-democratic groups in their appeals to Mrs. Sadako Ogata, 63-year-old Japanese professor, when she visited Myanmar last November as UN expert to investigate violations of human rights by the junta. Disguising himself as a port laborer, a monk, and a merchant, he managed, with the help of ordinary citizens and forged ID cards, to move around freely in ten different cities and to meet party, labor, and student union officials. He described what he had seen with his own eyes in Rangoon as if it were the scene of a movie.

“It must have been around eleven o’clock in the morning of the third. I had just come out of the building on Anawratha Street near Sule Pagoda where we had been talking about how we could manage to meet Ogata. Suddenly, and quite unexpectedly, Mrs. Ogata herself passed by in a car, escorted by several other vehicles. The group of about 50 students were watching to see if Military Intelligence had detected our meeting. As soon as they saw her car, two female students bravely stretched out a cloth banner so she could read its hand-lettered message: “WE WANT DEMOCRACY & HUMAN RIGHTS! WE DON’T WANT MILITARY REGIME!” The motorcade immediately speeded up, except for one car which turned back. The girls were forced into it, and it sped away.”

According to a Thai newspaper quoting a Rangoon-based diplomat, although Mrs. Ogata was scheduled to stay at Inya Lake Hotel, she was instead kept in a government guest house surrounded by heavily armed guards. Actually, her “house arrest” was even more severe than that.

Another time, knowing that a visit to Shwedagon Pagoda is de rigueur for any visitor to Rangoon, Ye Htut disguised himself as a monk and waited for Mrs. Ogata there. She finally appeared, but the Pagoda precincts, always crowded with Burmese people, had been emptied and declared off limits to the public. Moreover, she was so closely guarded by officers escorting her that it would have meant his certain arrest had he tried to speak to her.

The Thai Airways plane from Bangkok that was hijacked was originally scheduled to carry Mrs. Ogata on her return from Rangoon. Although the hijackers didn’t belong to ABSDF, it seems their minds were much the same as Ye Htut’s.

According to reports from underground organizations in Rangoon, 250 persons were arrested for attempting to get documents detailing human rights violations into the Japanese Embassy or for trying to speak ‘the truth’ directly to Mrs. Ogata. “I photographed some of the documents,” Ye Htut told me, and “managed to bring the film out to Bangkok, but because I had only a cheap camera, everything was out of focus.” How could he help but feel vexed?

A month after her investigation in Myanmar, Prof. Ogata was appointed United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the role she is now carrying out in Geneva. Only she knows whether the banner the two girls held out, in defiance of arrest, caught her eye.

“Dear Big Father, I remember you…… Please come back as soon as possible.” Aung Myint (fictitious name) (39) choked back tears, and his voice broke as he translated the careful handwriting for me. This second spy, the commander of the underground section, hasn’t seen his six-year-old son since September 22, 1988. The letter had safely reached him after passing through many obliging hands.