Burma(Myanmer) Sings for DemocratizationMay 1990

In Burma, 1988 thousands of students and ordinary citizens were gunned down when the army shot into massive pro-democracy demonstrations against Ne Win’s 26-year-long dictatorship. Their consolations finally came in the general election held May 27, with its landslide victory for the op-position. The military gover-nment, however, has not yet acknowledged the people’s will; martial lawremains in force. The protracted dictatorship has brought the nation to bankruptcy, and after years of strict censorship and police-state surveillance, the people whisper and shudder in fear of arrest and imprisonment. Torture in prisonis known to be a common occurrence. I listened to their voices and heard what they couldn’t say openly.

OVERCOMING FEAR AND SPEAKING OUT

A week before Election Day, thousands of people crowded into the campus of Yankin Teachers’ Training College in the capital, Rangoon.

“The fires at the Khemapyu State Iron Works have been extinguished for a long time,” a manager told me. “Why?” I asked. “When it’s closed,” he answered, “We lose one million Kyats. If we operate it, we lose two million!” “Is that right?”

This was part of a skit by the popular 29-year-old comedian Zarganar. He was once a dentist, but three years ago his sarcastic wit brought him fame as a stand-up comic. At first he was popular even with the authorities, appearing on TV and in movies. The evening after the performance at the college, the police suddenly appeared at his house, arrested him, and took him to In Sein Prison where an estimated 2,000 political prisoners are held. Zarganar was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment.

“There is no place more terrible than In Sein,” said his brother, a magazine journalist who was also jailed there for three years in the 70’s. “Seven people are squeezed into one filthy room. There are lice even in the rice.”

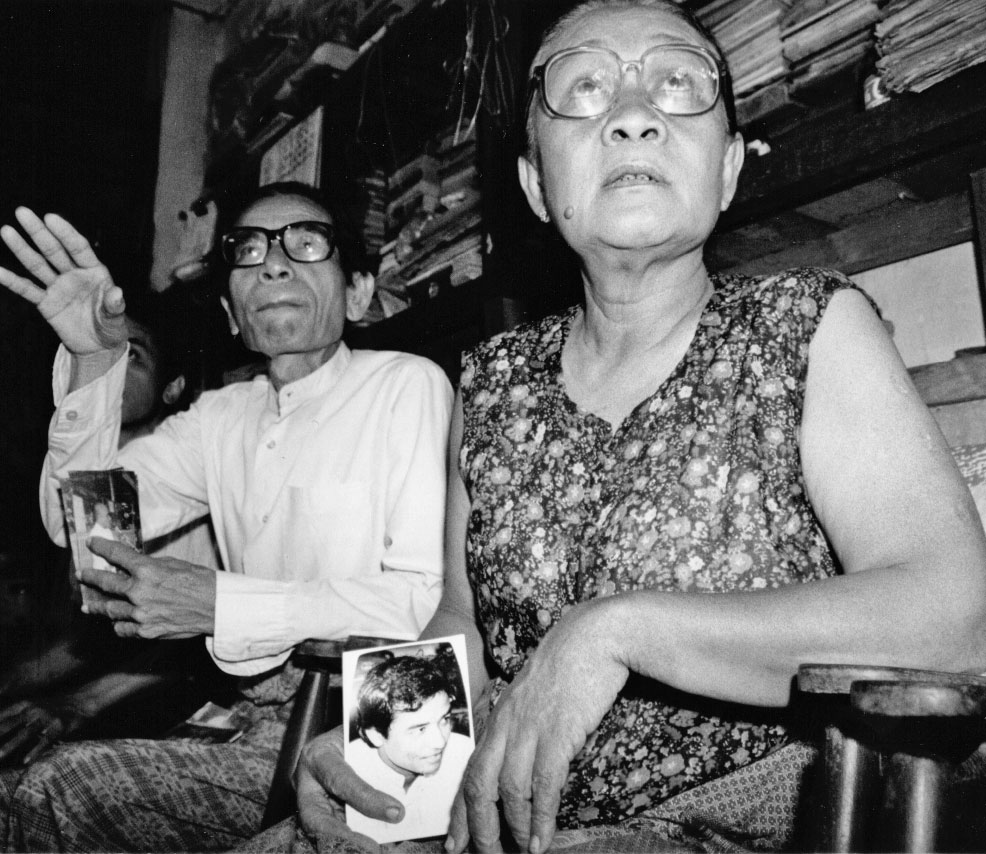

Their mother, Daw Gyi Oo, could only talk to her son through a metal grate. “My son asked me in a loud voice, ‘Who is winning?'”she said, “even though three soldiers were taking down every single word we said. When I told him, ‘NLD has won more than 400 seats,’ he looked delighted in spite of his bitter experience……” Daw Gyi Oo is an authoress of historical novels. “I admire bushido spirit (the code of the warrior),” she said in broken Japanese.

“Keep your eyes open, and observe what has happened in this country,” Zarganar’s brother begged. “When you see what’s wrong, help us by any means you can. I can’t believe the government will peacefully transfer power to the NLD.”

Anxious about his security, I asked the brother,”Wouldn’t it be better not to mention your name?” “No!” he cried. “Write our names please!” He was trembling violently, as if he had malaria.

TURNING A SILK PURSE INTO A SOW’S EAR

“The government is a thief !”cried U Than Win = fictitious name, a former navy captain who has been to Japan about twenty times, clenching his fists with all his might. Three years ago, three denominations of bank notes were suddenly abolished and in an instant the savings of ordinary people became rubbish. “I thought big notes could be dangerous,” he continued, “so I kept a lot of money in twenty-five Kyat notes, but I saw two hundred thousand Kyats go ‘poof’ and varnish into thin air!”

The Burmese people were infuriated by this abrupt action, and their anger over devaluation helped fuel demonstrations from July to October, 1988. During the recent election campaign, U Than Win was disgusted by an incident that happened to him. “A candidate of the ruling party called at my house,” he said. “He offered privately to exchange those canceled notes for new ones. How dirty their tactics are!”

U Than Win’s house is surrounded by tropical trees in a high-class residential area of Rangoon. Since he served for more than 40 years both in the navy and with merchant ships, Captain Than Win has gotten by financially without any great difficulty even during the impoverished years of the Ne Win regime.

Just beside this affluent neighborhood, however, there is a squalid slum. There, U San Maung=ficticious name, a 35-year old brick layer, lives with his family of six in a small house with a nipa roof. Their only light is from an oil lamp. U San Maung’s monthly salary is 800 Kyats. His brother works as a shop attendant and earns 250 Kyats. His sister brings in 300 Kyats from her work as a maid. They all live together. Their combined income of 1350 Kyats is equivalent to only 4,000 Yen at the black market rate.

“Even putting all our salaries together, we can’t buy anything except food,” U San Maung said. In contrast, Captain Than Win has a car, a stereo, an electric fan, and many other modern appliances, all made in Japan.

A Japanese watch costs five times the brick layer’s monthly salary. A television costs as much as his income for three years. Slums and houses full of imported items are neighbors, standing side by side. This great disparity in wealth is constantly faced in the streets of Rangoon.

The Captain’s family, rich by local standards, nevertheless, have an aching worry. Their daughter who supported the “Star of the democratic movement”, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, is in prison even now for her “political crimes.”

A BURNING VOTE

“Please follow my car,” a young man whispered to my driver. Forty minutes later we were still driving around to make sure we were not being followed. We saw the same lake on our left three different times. At last we arrived at the house of Dr. Hla Aung (fictitious name), a fifty-two year old lawyer. Nine executive committee members of the All Burma Federation of Student Unions were already there.

“Stand up!” someone suddenly shouted. The leader gallantly read aloud their demands. “One: to call a first session within one and a half months. Two: to invest the Diet with full power. Three: to legalize the unions of students and workers. Four: to stop the civil war immediately. Five: to form a civilian cabinet. Six: ……” They were resolved to send this letter to General Saw Maung, who rose to power in the brutal 1988 coup.

“Even before we ever appear in court,” said Dr. Aung who has been advising citizens and students since the demonstrations two years ago, “It is transparently clear that we will lose every case. Although we inherited our civil and criminal legal system from the English, our courts are powerless in the face of martial law.” Thoughtfully, he began to peel mangoes for the student leaders who seemed just like his own children.

As the election date drew near, tremendous fires mysteriously broke out in numerous places around Rangoon. Those conflagrations destroyed thousands of homes and seemed to be centered around houses which were giving shelter to students. The residents of the burned-out dwellings were moved to newsatellite zones outside the city. Other city-dwellers were forced to move under the guise of “urban redevelopment.”

Visited Shwe Pyi Thar (“Village of Happiness”), a satellite town to which many people were relocated after one of those unexplained blazes. It is a full thirty kilometers from Rangoon. A thirty-seven year old state factory worker talked to me as we stood in a vast expanse of rice fields.

“I went to vote,” he said, “but I had to go back to the polling place near where my old house had stood because my name wasn’t on the roll of this place. That day my wife and I left at five o’clock in the morning with many of our neighbors. We had to transfer trucks four times to get to the polling station.”

In Rangoon, the turnout for the election was as high as seventy percent. The people of the new satellite towns overcome many obstacles to cast their “burning votes.”

DEAD-END AID

The ferry I was on left Rangoon Port and passed by several new, grey steel warships, bristling with weapons. Most the other craft, for passengers and cargo, were old and wooden. On the deck of the ferry, a vendor in a rattan peasant’s hat was peddling the publication of the National League for Democracy, which had just won a landslide victory in the election. A young uniformed soldier stared intently at the large picture of Aung San Suu Kyi on the front page. After sailing southeast for about an hour, the ferry passed a bridge being built by the Chinese and arrived in Syriam.

Sixty percent of all foreign aid is concentrated in Syriam. The state oil refinery there, begun in 1981, was completed with an eleven billion yen loan from the Japanese government and loans from OECD for an additional eight billion yen.

Perhaps I was asking too much, as I tried to get some good shots of the refinery through my telephoto lens. “If the soldier catch us photographing,……” whispered the driver, who was visibly scared. Colorful birds flew around the huge structures, and goats cavorted near the fence. No heat waves were shimmering at the tops of the tall stacks.

Mr. A, a newly-elected NLD candidate, used to be a manager at the refinery and he spoke candidly about its actual situation. “Although the plant should be fining out twenty-six thousand barrels a day,” he explained, “it is producing only three thousand barrels. The government doesn’t have enough foreign exchange to get crude oil to bring the refinery up to full capacity. This modern complex was constructed by Mitsubishi Heavy industries, and can be run by as few as two hundred engineers, but Rangoon is inundated by tens of thousands of men out of work. This is another example of gross miscalculation in economic planning by the ignorant military,” Mr. A pointed out.

“It’s a vicious cycle here in Burma,” he emphasized. “Other factories run short of materials and power because of this refinery’s stoppages and low output. Since those factories can’t produce enough, the whole country depends on imports for even the most basic daily necessities, so there are no foreign exchange reserves”.

“Even after losing the war, Japan could prosper and rebuild the economy because you had a lot of talented men,” Mr. A continued. “but we are losing our best talent. University students and graduates are leaving the country in droves –every day. Soon there will be no one with any brains left! Of course, foreign assistance will be necessary at first, but as soon as possible, we have to recreate an independent and peaceful country where everyone can work freely and productively!” As he said this, Mr. A gave a deep sigh.

Japan provides eighty percent of the foreign aid Burma receives so Japan is the power the government listens to first.

THE LIMITS OF PATIENCE

“We must control our minds and not give vent to harsh speech. This is the teaching of the Buddha.” With this, Daw Khin Mar (62) avoided directly answering my questions. “When you come next time, we’ll be able talk……,” she added.

She is the wife of U Tin Oo (63), the chairman of the National League for Democracy. Her husband is now in prison and has been sentenced to three years because he supported the military who had demonstrated for democracy. I could feel the weariness and frustration behind her composed smile as I left.

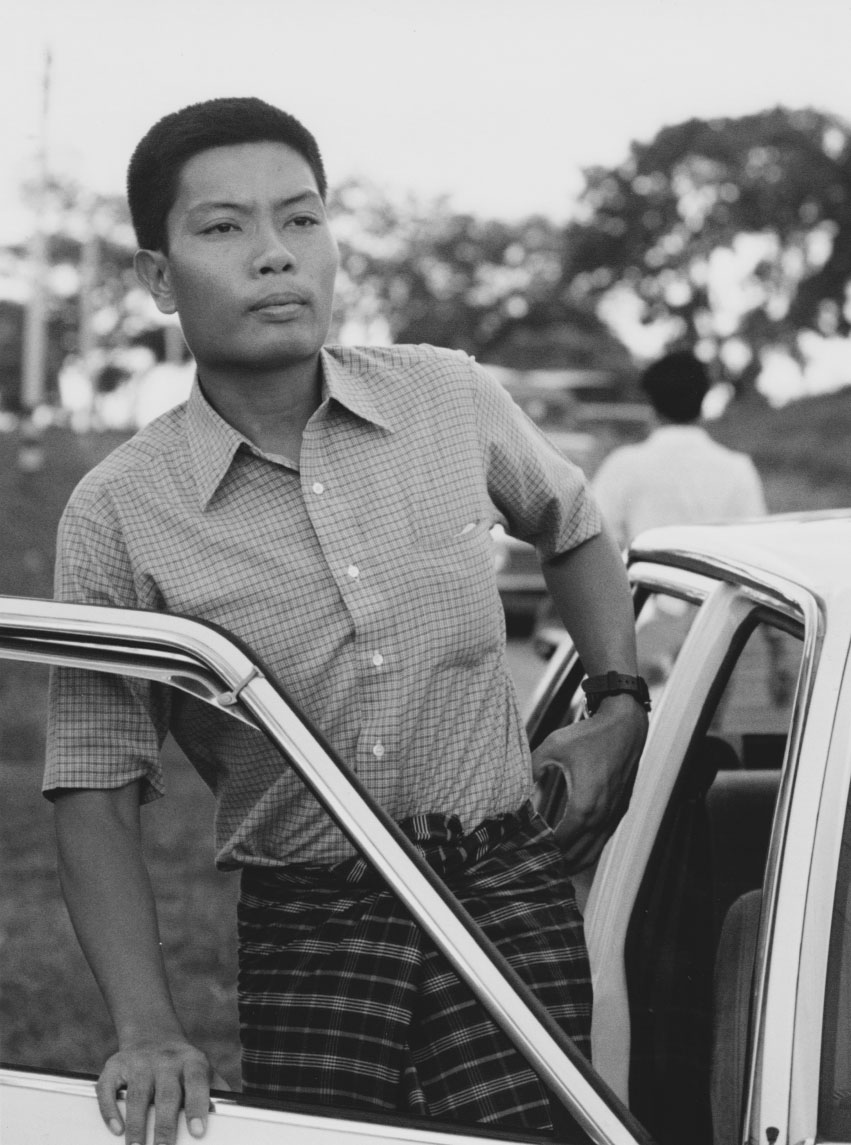

Their twenty-nine-year-old son, Thant Zin Oo, drove me to Mingaladon Airport. He has a strongly-built body and a well-tanned face, with a short haircut which makes him look like a young military officer. “When I was a boy,” he told me, “I wanted to be a soldier, but Mother didn’t want me to because I am her only son after my younger brother’s death. I’m not at all suited to be a politician either because I have a quick temper. So I’m looking for a job.” He also spoke to me in Japanese which he learned in Nagoya where he was a trainee for auto companies from 1983 to 1985.

“My father was in the Ministry of Defense and came home late every night,” he continued. “But once, when I was in junior high school, he took me to a militaryreview. I was sitting right in front of the national flag, so in the official films shot that day, I was more prominent than any of the dignitaries.”

By the time he came to Japan, however, everything in his life had changed. “One day Ne Win called my father to his house for a meeting,” he said, “and suddenly dismissed him. My father fell out of favor and wasn’t able to get any other position. He became a monk for a couple of years. When he saw me off at the airport, he was stopped by guards at the departure lobby just like any ordinary well-wisher.”

As we drew closer to the airport, he seemed to have made up his mind to speak frankly and openly. “If things are left as they are,”he said firmly,”the NLD will be treated badly by the military. History could repeat itself, just like when Ne Win overthrew U Nu’s elected government in 1962. As if foreseeing his imprisonment, Father wrote letters to Ms. Takako Doi (Chairwoman of the Japan Socialist Party). We wonder if she received them. Please,”he entreated,”ask the government of Japan to press the military government of Burma to release my father, Aung San Suu Kyi, and U Nu immediately.”

He stepped on the accelerator and suddenly changed the topic. “Japan is a nice country, isn’t it?” he said in a completely different tone. “You can sing Karaoke with your boss just like a friend. You can stay out until midnight and go home easily by subway or taxi without worrying about a curfew. The next day you can go to your office at nine o’clock, and everything is in order. I admire that!”

He sighed softly and began to hum “Yagiri No Watashi,” a sentimental song that had been popular while he was in Japan.