Burma(Myanmer) In the Gap Between Democratization and Economic DevelopmentDecember 1993

Burma —– the land of the “Burmans,” the Bamah people. Myanmar-the official name that appears on world maps, inclusive of Shan State, Karen State and other territories. In July 1989, the military government formally changed the country from “Burma” to “Myanmar,” as if to say they’d made peace with the ethnic minorities; while those opposed to the military dictatorship, the exiled democracy movement and its supporters overseas still call it “Burma”. Yet in the country, people go on using “Myanmar” as they always have in Burmese, an indicator of the different “temperatures” inside and out.

In August 1988, while Burma was still under the Ne Win regime, the military opened fire on pro-democracy demonstrations, spilling the blood of students and citizens. The State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC; Saw Maung, Chairman) which seized power in a coup d’etat then arrested and imprisoned Aung San Suu Kyi and other leaders of the National League for Democracy (NLD) as “political criminals.” In April 1990, the NLD won an overwhelming victory the first multi-party General Election held in thirty years, but many “political criminals” have yet to be released nor has there been any transfer of authority to civilian government. Meanwhile, a National Convention of over eighty per cent junta-appointed representatives have drawn up a military constitution which effectively annulus the General Election the world had witnessed.

This past December 24, three years since my last visit, I returned to Burma tocheck up on allegations of human rights abuses made by pro-democracy movement abroad. At the same time, I saw the realities of economic “opening up” and liberalizing policies that I was not prepared to see. Here, then, is the account of my eight days “inside,” weaving through bureaucracy and troubles to catch glimpses of Burma today.

INDEPENDENCE DAY

January 4 is Burma’s Independence Day. In Tokyo,some fifty Burmese residents ofJapan together with Westerners and Japanese marched with placards Free Aung San Suu Kyi Immediately! and Uphold the Election Results-Implement Transition to Democratic Government! The demonstration, held on behalf of the Burmese populace still captive inside the junta’s own “colony,” was dead silent to under score the denial of freedom of expression.

A young man who’d recently arrived in Japan on the same plane with me came along to “observe.” He’d seen demonstrations like this six years ago, and it was six years now that his father, a famous politician in Burma, had been locked up in prison. Even so, he had few kind words. “This sort of thing won’t make a bit of difference, not with that country. I’d hate to spoil it for everyone, but I doubt anyone sees them except as illegal immigrants come here for the money.”

VISA

Since 1990, when my newspaper reportage on the General Elections had “not amused” the military government and my foreign correspondent’s press card was revoked, I’d been persona non grata.. But with the National Convention last January, they’d started letting journalists back in. Deciding to give it a try myself, I applied to the Myanmar Embassy and a visa was issued the very next day, no hitches. Whether they simply wanted tourist foreign exchange, or they didn’t mind what travelers told the world about conditions inside the country, the junta was obviously quite confident.

CHRISTMAS EVE

The plane to Rangoon was not the exhausted old F28 of three years ago, but one of the B757s that Myanmar Air had begun operating under lease from Singapore. Yet just seconds before landing I had to strain my eyes to even make out the streetlights of Rangoon, a city long cut off from Western aid.

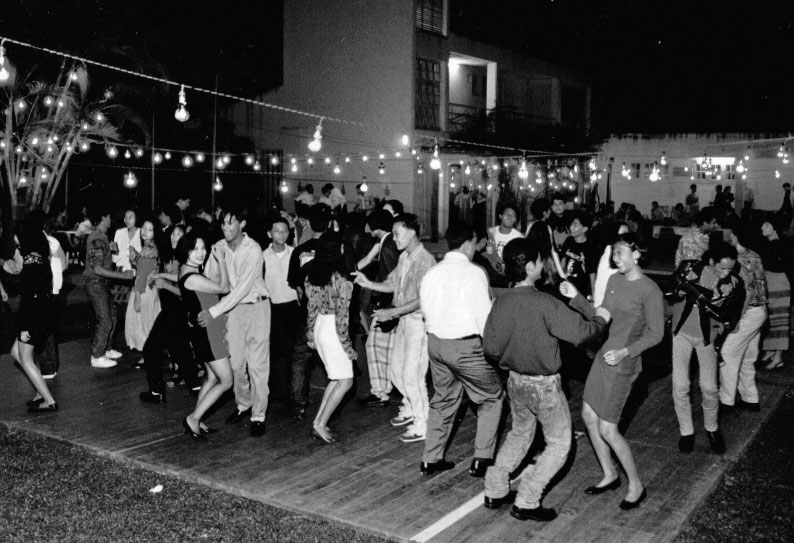

The night of my arrival in Burma was Christmas Eve. I dropped in on a poolside dance party. Young men in jeans and women in skirts and high heels, where I remember most would have dressed in traditional longyi (sarong). All were dancing away, having a wild time, as coconuts bobbed on the pool.

“Can you believe it?” a caucasian man came over to ask, gin tonic in hand. “Now people get a little money, they can blow off their troubles.” First Secretary ata Western embassy, he informed me that over ten karaoke bars and night clubs had opened in Rangoon this past year. And true to diplomatic form, he added his analysis. “It’s just one of SLORC’s ‘pressure valve’ tactics. The junta still only has maybe $26 million in reserves (late official figures placed it at $16.6 million in August 1992). That wouldn’t last three months without this year’s income. You just know they need money. Although there’s also the view that they’re so sure their control they no longer care what meets foreign eyes. But that’s a bit over the top, I think. They’ve hardly given this much authority to the elected representatives of the National Convention,” he said, gesturing a pinch of the fingers.

At a table on the far side of the pool sat a woman in a black dress, former aide to Aung San Suu Kyi, who was seeing out her fifth Christmas Eve under house arrest not ten minutes away from here by car. Like Suu Kyi, this woman had also been imprisoned on July 20, 1989, but was one of some 500 “political criminals” released over a six month period from April 1992.

“Care to talk?” I suggested. “Let’s dance,” came the reply. Waiting until the loud rock music died down so we didn’t have to shout, we danced a slow number. She spoke under her breath. “I haven’t seen her at all since then. I haven’t even dared to contact her husband (Oxford professor Michael Aris) . . .” Even someone this close to her had no more access to information than the trepidacious foreign wire services. The second chorus played. In Burma, where not even newlyweds hold hands in public, here was this woman, a lawyer no less, bodily snuggling up to whisper in my ear. “(In prison) there was no physical torture or drug-induced brainwashing. If that’s what the Western media is saying, then let them know that SLORC’s ‘education’ has completely failed. Not one of us political criminals’ have bent in our beliefs.” The last dance was over. Amids shouts of Merry Christmas!, she left me with one last caution. “Keep me anonymous.”

THE BRAINS OF THE PRO-DEMOCRACY MOVEMENT

The next day, December 25-Christmas-I visited the cottage home of former ‘political criminal’ U X (58). Jailed in October 1989, he was another of the ones released after April 1992.

“At the time I got out, there were 800 of us (in Rangoon’s Insein Prison). There’s got to be 500 still in,” he reckoned from the breakdown of cells and the number released. He ought to know; he’d been jailed seven times in the last thirty years. “And Insein’s not the only prison. There are dozens more in different parts of the country. There must be a thousand more in prison. In the Irrawaddy Delta, whole peasant villages with no political color whatsoever were all thrown in jail, then set free. The arrests were never made public, but the releases were announced to the Western press. That way, they could play up their appeasement policy to the West without freeing any real ‘political criminals’.”

In October 1992, after this string of releases, SLORC Foreign Minister Aung Kyaw voiced the junta line on his visit to Japan. “Until state stability or safety can be assured, military rule will continue. The detainment of dangerous elements is entirely normal, and anyway they number far less than 1% of the population.”

U X described treatment inside Insein Prison. One to five persons were kept in a cell scarcely 8 feet square (approx. 6.5 m2), and they were only allowed out once a day for fifteen minutes. If they weren’t quick to shower, they’d have no time outside. There were two meals a day-rice and bean gruel in the morning, plus a soup “with weeds dumped in” at night. Meat or fish they might see once a week, or not at all. Clothes were limited to two shirts and a sweater, one cotton blanket and one rough flax blanket. But in winter, even wrapped up in all that, it was too cold to sleep, so they slept during the day. Furthermore, the tiny closed cell was stifling hot in summer, so again they got no sleep.

Family could visit once every two weeks, for fifteen minutes. Whatever was spoken through the wire grating was written down in entirety by guards on both sides. Gifts of food were allowed, but were restricted to 800 gm each of up to five items of fruit, dried shrimp or other stock at the prison shop. If they took ill, they could turn to their families for medicine. But say illness struck right after one visit, they’d have to wait until the next visit to ask, then wait another two weeks for the medicine, or a total of four weeks.

On the subject of torture, he said, “I myself was not tortured physically. But in solitary confinement, without anyone to talk to, you’d get so depressed your mind would go numb. So in that sense, you could say there was plenty of mental torture.”

One student (27) still imprisoned since immediately after the 1988 bloodbath started growing vegetables to pass the time inside, his father told me after one of his visits. In late 1988, I’d reported incidents of students so badly injured in jail they died soon after release; lately, however, the goal of tightening security seems to dictate isolation of popular pro-democracy opinion-leaders from the people rather than thought modification through torture and heavy labor.

According to U X, when it came time to be released, there are questions about one’s “crime”. An NLD member will be asked, “What do you think about Suu Kyi?”In his case, he was asked three things: 1. His opinion of SLORC; 2. Did he recognize the National Convention?; 3. Once freed, what would he do? And within the limits of conscience, he could answer: 1. He believed SLORC in its declared intention to deliver democracy; 2. He recognized the National Convention as a step toward democratization; 3. As he was getting old and didn’t want to be jailed again, he would not involve himself in political activities. “I couldn’t hang out a banner anyway. Too many good personnel are still in jail,” he admitted, now dedicating his efforts to trade.

At one time the “brains of the pro-democracy movement,” he’d told Suu Kyi who envisioned a Gandhi-like non-violent people’s revolution, “Yes, but Gandhi succeeded precisely because he had the support of an army.” The prequisites of arevolution, he reminded her, are: 1. Charisma; 2. A practical philosophy; and 3. Trustworthy power. Her timely return to Burma won her charismatic appeal, but she needed to “get a working formula, not just spout democracy.” Moreover, he even worked behind the scenes to try to get elements of the national army to back her up.”She gained the support of the great majority of the people, and she alone embodies their hopes. With any other leader, everything would break up like the former Soviet Union.” But as for hopes of her release, “She won’t come out in any compromise situation.” Since November 1991, when her Nobel Prize was announced and Burma’s UN Ambassador Kyaw Myint stated that “Her house arrest will be lifted at any time on the condition that she leave the country,” she has rejected such offers. The reason being that through her husband’s visits she is aware that she’s become a symbol of democratic aspirations, not just for Burma, but for the whole world.

Nothing that the economic sanctions merely hurt innocent citizens and prove ineffective against the dictatorial regime, he proposes other concrete measures.”First, a total arms embargo, then no visas for SLORC dependents seeking to study overseas. A mere hundred or so of their second generation are trying to perpetuate the dictatorship.” Some would argue that present levels of economic growth are at the point of creating a middle class in a civil society, but under these conditions only the “military class” is expanding. Giving SLORC warnings amounts to giving them confirmation. They’re desperately trying this ploy and that just to gain time. Conversely, time is on our democratic side. Because we haven’t twisted our principles out of fear, we’re just waiting for the moment to gain strength,” he said, reaching a framed photo from the sideboard. His son, a smiling youth had hurried back from studies abroad only to lose his life at age 23 on the Thai border fighting for democracy in his country.

THE HOME OF THE EXILE

Long hair to midway down her back, wearing light make-up, she came out to meetme. Only three days before, her exiled husband had called from New York to tell her a reporter would be visiting. Apparently the wires were not being tapped lately. Climbing the teak stairs thick with dust, she led me to the large sitting room.

Her husband, a leader in the August 1988 pro-democracy demonstrations, had fled the army’s guns to the jungles on the Thai border and even became first chairman of the student camps. Last year, however, sandwiched in by pressure from the Thai side, he’d sought refugee status in America. While he was hiding out in the jungle, his mother had managed to sneak messages to him three times, but his wife was under surveillance and had not seen him in almost five and a half years.

“Actually, in January I’m going to America with the two children. The way things are now, my husband’s absolutely not coming home. He’d be arrested second he stepped off the plane.” Burma began to issue passports for ordinary citizens in 1993. It seems that the junta wants to get rid of “trouble-making” intellectuals, while at the same time banking on the foreign currency they’ll send home.

She said she’s not concerned if the country does not immediately become democratic. It would be enough if all “political criminals” were released and no more were arrested as such. Just do that and she’d glad come back. After all, she said simply, “I love Burma.”

ABSDF

Back in Bangkok, I’d heard about the current situation in Thailand and how many people like her husband had been driven out. Ko Y(27) of the All-Burma Students Democratic Front (ABSDF) Central Committee told me that of the nearly 8000 students who’d gone into hiding in the jungles in 1988, only some 2200 remained in their fifteen camps. About 1500 were on the Thai border, the rest were on the Chinese and Bangladeshi border or in New Delhi in India. Of the over 5000 others who’d left the camps, many had either returned of the own accord or been forcibly repatriated; still others had taken refugee in third countries or were whereabouts-unknown.

In November 1988, twenty-one ABSDF units, along with various ethnic minority andreligious groups, had come together to form the anti-junta Democratic Alliance of Burma (DAB) based at in the Karen capital of Manerplaw near the Thai border. Starting from late October last year, however, SLORC had launched a “reconciliation policy,” signing a ceasefire pact with the powerful DAB member Kachin Independence Organization (the 6000-strong KIO; Brang Seng, Chairman). Previous ceasefires with the Pao in March 1991 and the Karenni in January 1993 had already reduced the original eleven-member DAB to only six groups: the Karen, Mon, Arakanese, Chin, Palaung and Wa. Then at the end of last year, as President Bo Mya of the Karen National Union (the 5000-strong KNU) declared that no group was to enter into individual negotiations or comply to ceasefire discussions sponsored by SLORC, the Burmese Army launched a fierce three-division assault on Manerplaw’s defence position at Soe Taw.

Meanwhile, some five-hundred Burmese students like Ko Y moved in and out of Thai territory making appeals to the world at large and trying to stir up support. Some among them received monthly support from the UN High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR), but the actual amounts had declined from an initial 3000 per person in 1988 down to 800 (approx $32). Braving arrest to work illegally, the students worked out an existence making bricks and trading in used clothing.

But now, in addition to military assaults against the student camps, a new threat now menaced them. “Thai policy toward SLORC has changed completely. It’s total SLORC-support. Everyone’s scared of when they’ll get turned in,” he spoke of the dangers. Early last November, after a Thai military command visit to Rangoon, Thai Foreign Minister Prasong Soonsiri announced stepped-up policing of Burmese engaged in “anti-government activities.” That same month, the Thai Ministry of the Interior placed 120 Burmese students in a new “safe camp” in Ratchaburi 100 km west of Bangkok. Then, after December 3 when the authorities detained 30 Burmese students attending a Thai NGO-sponsored human rights study group, the arrests accelerated and intensified. In just the one month prior to my seeing Ko Y, 70 students had been rounded up.

Last December, the ABSDF did the previously unthinkable and declared its readiness for talks with SLORC under certain conditions: 1. that the talks comprise four parties, students, ethnic minorities, National Convention members and SLORC 2. that talks be held neither in Burma nor Thailand, but in a third country; 3 that UN and journalist observers be present.

Yet the proposal went unheeded as the DAB’s mainstay KNU announced its willingness to accept individual peace negotiations. After 47 years of unbroken struggle, even the KNU was getting the cold shoulder in Thailand’s change of sleeping partners. Where the KNU had previously used American-made weapons secretly sent by former-president Carter prior to the 1990 election, it seems this abrupt about-face signalled a shift in US policy toward Burma to Gen Bo Mya on his visit to America last autumn.

NLD MEMBER

Meanwhile, back in Rangoon, I went to see the NLD headquarters out of nostalgia for the days of the General Election when supporters had thronged and cheered around a stage set up on the pavement outside. The cinema-style billboards of

Sec-Gen Suu Kyi had been taken down; only the peacock-emblem party flag gave any indication that this the NLD headquarters. The fever had chilled to an eerie stillness, as if it had all been just a rumor. The driver nervously broke the silence, “Plainclothesmen! Don’t even think about it.” I waved the car on without getting out, when a middle-aged man with wire-framed glasses out suddenly appeared out of a curry stall on the street and made straight for us.

An NLD member (45) I’d happened to meet out walking in public, he talked while we rode in the car. Mid-November last year, he’d met unofficially with UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights, Prof Yozo Yokota, but the talk was only about his shipping company. “He probably thought it better not to put me in trouble by asking about politics, but I myself wanted to tell all. Bearing witness to someone comes here as the eyes of the world conversely guarantees safety.”

According to him, just last July 17 before the reconciliation policies, they’d arrested some 30 to 40 students who attempted to offer flowers at the Martyrs Mausoleum of Aung San, along with 21 students who’d made a video for foreign TV news, and handed down a maximum 20 years sentence. “We intellectuals tend to shrink from meeting foreigners, but when someone like Yokota or a journalist arrives, we ought to rouse our courage and make contact,” he spoke without hesitation, though he too had suffered imprisonment.

LAMENT OF AN ELDER STATESMAN

In the General Election three years before, the NLD won 392 out of 485 seats, a full 81% of the People’s Assembly. But now in the National Convention “to decide basic principles for a new constitution,” the numbers of elected “party representatives” had been diluted by SLORC appointing additional ethnic minority, peasant, laborer, civil servant and military representatives, for a total of 702 seats. Convened from January 19, 1993, non-appointed participants counted only one seat in seven.

On December 26, I was invited to dinner by Col Z (62). One of the very few members of the former ruling Burma Socialist Program Party (BSPP) to win a seat in the General Election, he now also attended the National Convention. “Political awareness among the appointees? They don’t even know what tripartite division of powers is!” he could scarcely conceal his irritation. Flipping through the roster of the National Assembly, whose sole reason for being was to issue a flimsy pretext for arrests, Col Z counted out, “There’s only 107 Assembly Members who were chosen in the General Election.” But that was not the real problem. “Lots of those elected weren’t professional politicians at all. You’ve got literary types, historians, engineers, any old fool who’d caught the democratic fever. Until elected, how many of them had the thinking gear to voice opinions in committee on articles of constitution?” No, he regretted, the General Election had been swept along on a mood.

When I inquired about what went on in the Assembly, he responded with a seasoned politician’s analogy. “I hear that soccer’s gained popularity in Japan. In our game, using the hands is not an offense. But then, we can’t even see where the ball is . . .” According to another elected pro-democracy representative (42), nine tenths of the 107 are NLD. Still, the sessions were closed to the public and all statements had to be submitted in writing beforehand, so there was no freedom of speech. When a few brave souls raised objections to Assembly Chairman Aung Than’s comment that “the new constitution highlight the role of the military,” or to a military representative’s that it reserve “a leading role for the military in times of emergency,” but they were soon censored. If you spoke up “guerilla style” without a prepared text, the Chairman would cut short your allotted time, or if you kept talking, you would be hauled off by security guards.

Shoulder to shoulder with my brother, we go to school thanks to our soldiers・・Col Z sang an old Japanese Army song after a few drinks. “Japanese Army disciplinary measures were unreasonable, but I admired their sense of unity,” he repeated. To be sure, unity is the principle “weapon” of the pro-democracy movement. But now was indeed the moment of truth, as cracks were becoming apparent among pro-democracy organizations both inside Burma and abroad. In the Japan-Resident Burmese Association there is a parting of the ways between the Tokyo and Nagoya groups over the organization’s own democratic practices. In the ABSDF Thailand, a split occurred when the former Chairman sought the support of the Burmese Communist Party. And within Burma itself, factions broke away from the NLD one after the next, rapidly reducing party membership by over a hundred. All the way back to the first post-independence General Election of 1951, when “Father of Burmese Independence” Gen Aung San’s own party won a landslide victory, the ensuing internal disputes left and right provided a precedent for military intervention in politics up to the present day. “Even in this most crucial of times, we Burmese and we splinter,” lamented this elder statesman, almost nostalgic for the totalitarian unity of the Japanese Occupation Period.

It ired Col Z how his many contacts in Japanese corporations were asking about when to invest. Came the proclamation of the new constitution and the transfer to civilian government, it was only a matter of time. When I asked when that might be, he pulled a lottery ticket from his wallet and answered, “Can you tell if this is a winner or a loser?” Col Z was also well acquainted with the suspicious land dealings of the Tokyo real estate concern MCG. According to him, MCG plotted together with the Myanmar Ambassador to Japan, who was alarmed about prospects for the future as the pro-democracy mood came to a head back home in Burma, and in January.

“The only ones who come here are opportunists trying to make a fast profit before the smoke clears,” he barely concealed his anger. The scale and risks of infrastructural improvements needed to attract foreign investment are too great, unsurmountable for private enterprise. It’s not a job for Korea or Singapore or Thailand, despite trade moves toward Burma; in his view, only America or Germany or Japan can manage it. “And anyway, no reputable company’s going to come anywhere near so long as there’s such a ridiculous spread between official exchange rate and the black market rate,” grieved Col Z from bureaucratic experience.

JAPANESE JUNIOR DIPLOMAT

“Like the Ambassador himself exclaimed after his last visit to Tokyo, ‘The recession’s really hurting’.” As he saw it, things are really getting serious when Japanese companies are getting routed even in Burma. “In cars and appliances, we’re completely undercut by Korea and Singapore.”

Even today, Japanese ODA comprises 80% of all bilateral ODA Burma receives. While pro-democracy elements tend to make a case of Japan’s support of the junta, in fact, aside from some minimal technical assistance, both tied and untied aid has been curtailed since 1989. Whereas up until 1986, Japan loaned over \400,000m in monetary assistance generating an interest debt of several \1000m annually, this was as a relief mechanism provided for in the UN Conference on Trade Development, he explained.

Furthermore, he noted, “The US is now the number one private investor here, with Japan coming in sixth or seventh.” Granted, according to my own data, in cumulative tables for 1988 on, Japan may well be number seven in numbers of investments, but in terms of money invested it is number three after the US and Thailand. Not just the East Asian NIEs and ASEAN countries who have nothing to lose because of their own rapid growth, the West is also beginning to invade this virgin marketplace in an effort to offset recession, unemployment or other problems at home. “While Japanese companies await the re-opening of ODA, private interests have to stand in where the government no longer fields for its major players.” An irritated air seemed to be stirring in the Embassy.

Starting from last April SLORC Sec-1 Khin Nyunt has embarked upon a policy rapid-fire alleviation of grievances, ceasefires with the ethnic minorities, visitation privileges for Suu Kyi’s family, initiating release of political prisoners, lifting curfew, accepting back Rohingya refugees, holding the National Convention. “There were any number of opportunities for Japan to re-open talks and assistance, but the Japanese government stopped short at making pronouncements through the Embassy here. The Burmese may still pay lip service to the notion of ‘a special relationship with Japan,’ but their hearts are no longer with us. We’ve lost our influence here,” he commented in light of the reconciliation policies, pointing to the diplomacy gap with the West, whose money if nothing else kept coming in through private channels.

The junior diplomat was also less than pleased with Japan’s media coverage. “Even with the Rohingya issue, they criticise this government solely on the basis of what they hear in the refugee camps.” If a bridge is needed to improve living conditions in a village, the state recruits laborers from nearby communities. Those who don’t see the necessity of that bridge or who are dissatisfied with their compensation take flight and talk of “forced labor,” he offered. Then last year, a TV crew that did a location shooting through the dispensation of the Embassy, went back to Japan and broadcast not the project they’d discussed, but endless footage of the shootings six years ago. He was furious.

When I mentioned I’d heard from Rangoon citizens that when UN Special Rapporteur Prof Yokota made an inspection tour of markets and hospitals last November, products and medicines normally in short supply had been lined up on the shelves beforehand, he deflated my argument. “Distrust between the government and the people that gives rise to such rumors is problematic, but that was your socalled ‘Burmese hospitality.’ If the government had been more capable of stealth and subterfuge like, say, the North Koreans, don’t you think they’d have done a better, faster job?”

Now on his second tour of duty in Burma, he defended the junta’s economic development policies. “Just look at the last five years. One-fifth of the New Win period, but since 1988 the growth is up tremendously. Sure there are problems, but the bottom line is living standards are improving. You can watch BBC on Star TV from Hong Kong because regulations couldn’t keep up with the spread of satellite dishes. If exchange continues like this by economic means, politics will just naturally have to loosen up.”

According to the SLORC Economic Review for 1993/94, the 1992 GDP was Kyat 55170m ($4790m at the actual market rate), up 10.9% from the previous year. In spite of which, civil servant wages remained fixed around K1200 per annum, while 1 kg of rice that cost K4 in March 1992 had risen to K12 by the end of last year. Prices for staple foods had tripled over the previous 19 months, eroding any sense of economic boom on the everyday consumer level.

The Japanese junior diplomat likewise talked about the “old lady” in disguised reference to Aung San Suu Kyi. “Meeting with Khin Nyunt, it wasn’t hard to see how this clear-headed man-of-action became SLORC Sec-1. He’s young (54) and he’s very sharp. Nor is he the autocrat Ne Win was. Still, he’s barely keeping the other old guard officers at bay, warning them “not to accept money that cannot be explained;” they’re all just waiting for him to stumble. So he himself would probably like to let the ‘old lady’ go, but if that resulted in demonstrations and the army opened fire again, he’d lose his standing. If that happened it’d be a much worse economic and political situation than at present, so I support Khin Nyunt.”

And did the Japanese Government take the same stance? He shook his head. And what of freedom for Aung San Suu Kyi and the pro-democracy leaders? Rather than make that a bargaining chip, he said, inviting Burma into ASEAN and APEC would speed the course of democratization. Now that bilateral relations already existed with China and with ASEAN member states, driving Burma into a corner was simply counterproductive.

A LONG-TIME BURMA RESIDENT

The Japanese diplomat’s views in counter to the prevailing world censure broughtto mind another similar opinion. Teru Takeda (39), one of the few long-time Japanese residents, had been teaching at the Rangoon Japanese School since April 1990.

“Prior to taking the job, I’d thought ‘junta equals evil,’ ‘Aung San Suu Kyi’s house arrest obstructs democratization.” But after two or three years living here, I had my doubts that the picture could be so clear-cut.” In the countryside of course, but also in Rangoon itself, the standard of living, the poverty was unimaginable. “Before visiting Pagan, I’d been told ‘people were living like back in the Middle Ages’. And in fact, people were living in raised-floor huts with no electricity. It was more like prehistory than the Middle Ages. Well before Western democracy. . . ”

Despite strict controls upon freedom of the press, the inter-ethnic fighting in former Yugoslavia is frequently aired on Burmese National TV, as if to show the people “the other alternative.” Burma adjoins five countries by land and these border areas abound with ethnic minorities. “Is there any other group besides the military that can hold the country together?” To be sure, Burma is experiencing a severe brain-drain. “The majority of citizens who started the ‘riots’ (sic.) seem to subscribe to the irresponsible illusion that if the army just left and the government became democratic their lives would suddenly be so much better.” But even if the NLD became the ruling party, he could still cite any number of obstacles to national development. Bureaucratic inefficiency, long overdue infra-structural recovery, human resource development, cultural issues .. .

“As I now see it, what everyone was shouting about at those demonstrations was not the ‘freedom’ and ‘human rights’ Westerners taught them. They were calling for liberation from their miserable lives here,” he said in retrospect.

BACKWARDS FLOWS HE BURMA ROAD

Cutting short these thought-provoking interviews in Rangoon, I flew up to Mandalay via Pegu, where Japanese scholars have begun restoration work on ancient monuments under the auspices of UNESCO. Then, in order to make Lashio by sundown, we drove full speed up Route 3. This road leading to Yunnan Province in southwestern China was the very same “Chiang Supply Route” by which the Americans once sent support to Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang in their combat against the Chinese Communists. Whereas now the lines of trucks carrying manufactured goods from China met an endless procession of trucks laden with Burmese fish and forestry products going the other way.

This was Shan State, home of the Shan people who fought Ne Win’s troops after the War and who had allied themselves with the Burmese Communist Party (BCP). Now the Shan had already left the Democratic Alliance of Burma under pressure from the junta, although only last February major battles raged between the Shan United Revolutionary Army and the Burmese military in the Linkhin district, leaving 61 dead and 150 houses burned according to official reports. Even today government soldiers brandishing automatic guns are seen in deep jungle outposts, in the gorges spanned by iron trestles.

Crossing numerous mountain passes, the road waved back and forth, multiplying the direct distance many times over. On the map, it’s 260 km from Mandalay to Lashio, but it takes a good 8 hours driving non-stop. Even in two-lane segments, only the center of the road is surfaced, and the paving is in poor upkeep and full of potholes at that. Since the middle of last year there’s been talk of Chinese plans to upgrade this Burma Road into a “Burma Highway.”

We stopped for a merchant whose car had broken down and gave him a ride to Lashio. “What with the ridiculous exchange rates, most trade is by barter. But as an agreement had yet to be reached on the amount for teak to exchanged for roadwork, no real construction had started.” Approaching Lashio, we spotted piles of cut logs lying beside the road. Timber destined for smuggling to China, the merchant informed me, but which lately was being halted.

AN OLD COMMUNIST

Here I met a former BCP member, Cadre D (68), who attributed both SLORC’s opening the China border and its path of negotiation with the DAB to China having severed ties with the Burmese Communist Party. In the years since 1944 he’d fought for independence, first from the English, then the Japanese, then the English again, and finally withdrawing here from Rangoon in 1980. On the wall of the apartment where he met me in secret hung a Japanese sword he himself had captured.

“The British Governor saw personally to all decisions, granting monopolies to foreign enterprises, selling lands, so that we realized that true independence was still a long ways off. In 1948, the year of Burma’s independence, he joined the Communist Party and went underground. “At the time, the BCP was extremely popular, just like the NLD. Nobody liked the government, it seemed,” Cadre D said with pride. If the BCP hadn’t at that time, he praised the Party’s resistance efforts, Ne Win’s fascism would have followed on the heels of Japanese militarism.

Then in 1950, the year after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, they first succeeded in making contact with the Chinese Communist Party. After which they sent over a hundred men into China for cadre education, while eliciting weapons support and People’s Liberation Army advisors to bring Shan State and Khachin State under their control. Still unable to find a means of shipping arms to resistance elements to the south in the Pegu Yoma and Arakan State, the southern BCP was forced to fight with weapons confiscated from government troops. But what reduced their numbers to a mere 200 after all of thirty-two years of anti-government activities was not, he asserted, China cutting off support. “It was because from around 1976, Sec-Gen Than Tun and other Central Committee cadres took to acting like Mao demigods, and just like in China’s Cultural Revolution, demotions and promotions among the comrades, rampant assassinations splintered the Party core into factions.”

Even now, insisted, communism was not wrong, but Stalin and Mao had failed. “Look at the world. In what country do you see an expression of communism? We’re still on the way.” In his view, even if unsystematic economic liberalization widens the gap between the rich and poor, the Communist Party will never regain control in Burma. The Burmese remember how, even in BCP-controlled territories, former landowners’ sons and officials’ sons were the ones who became leaders. “In that sense, the same goes for Gen Aung San and his daughter Suu Kyi,” he hinted at shadows behind the “star of democracy.”

“Innocent people always embrace the biggest, most unattainable dreams. Before any Communist Revolution, there needs to be a democratic government to tackle all the problems of poverty and education.” So, I asked, if he rejected the junta, how did he vote in the General Election? The old Marxist gave a sardonic grin and replied, “NLD.”

“In the end, we were used as a molecule of pressure for Rangoon’s advantage in negotiations with China.” Realizing this, he now harbors toward China. “They assisted us economically for a long time, but they were also tight with SLORC. I’m a patriot before I’m a Marxist. Do they now plan to use us in their deals with the whole world?” He seemed to sense China casting a bigger shadow over Burma than it ever had in his own day.

ARE WE IN CHINA?

Long past sundown we finally reached Lashio. The lobby of the Lashio Motel, opened just the month before, was floored with Yunnan marble. Here I was to experience the problems of exchange rates. A room for a foreigner costs $36, approximately six times the K720 a Burmese pays at the actual market rate of K115 to the dollar. At the official rate of K6 to the dollar, the junta skims off almost 20 times pure profit; while calculating backwards at the official rate, K216 works out cheaper than the Burmese room charge. Whatever gives the junta the better deal. Payment accepted in dollars only, although you can also pay in Foreign Exchange Certificates, which travellers are obliged to purchase at US$1 for FEC$1 upon entering the country. This dual-scrip scam to shake down hard currency is something SLORC learned form the Chinese. These FEC “play money” bills even look exactly like Chinese FECs, only with Burmese script in place of Chinese characters. According to the manager, at least half of the motel customers were Chinese businessmen.

Stepping out for dinner, I was surprised to see a nightmarket in full swing on the chilly main avenue, the vendors’ pushcarts piled high with Chinese products. Figured in yen, a knit wool cap cost \515, a jumper \1250, a thermos bottle \250, an electric rice-cooker \1350, much cheaper than the goods coming from Rangoon or the Thai border. Burma sells China soy beans, ginger, fruit, dried fish, live crabs, lumber, cowhide leather, plus some stranger items like tiger lilies, and buys Chinese manufacturer goods in return. All courtesy of the fleet of brand-new Chinese trucks we’d passed that afternoon.

The shop owners were almost all huaqiao “overseas Chinese,” and invariably the shop signs were also written in Chinese. Said the young proprietress of the “Lai Lai Inn,” Zhang Jiuling (28), “Just last year when they started issuing one-week visas, the Chinese came rushing in. And not just old folks on pilgrimages. Young people, too. Seems everyone wants to see what’s selling in Burma.” She herself was born in Burma and had lots of Burmese friends. “There’s no problems between these new Chinese and the Burmese.” Rather it was the Chinese of her mother’s generation who were subjected to repression.

I asked her aunt (52) about those days, but was told, “It’s too horrible to talk about . . . Bandits often came to our houses and stole all our money and gold. Cross-border trade brought a lot of illegal cash, so we had to join forces with the Burma Communist Party. From 1967 to the mid-1980s, it was those “bandits” who put the visegrip on Chinese immigrants. “My father was a trader too, but only last year did business suddenly pick up,” said she, smiling again.

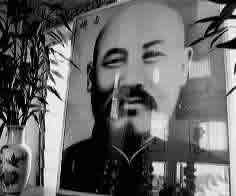

Next morning, I paid a visit to Longhuagong shrine in “Kuomintang Village,” as Lashio’s Chinatown is called. Burned to the ground only three years ago, this new reinforced concrete hall reminiscent of Taipei’s Chung-sheng Memorial Hall attested to the clout of the Chinese-Burmese community. Inside was even more of a surprise. There beside the colorful Theravada Buddha on the dias was a black-and-white photo of Chiang Kaishek bearing the posthumous dharma-name Tianran Gufuo, “Heaven-Thus Ancient Buddha.”

Bu shi Kungsantang, bu shi Kuomintang . . . The old men who welcomed me at the shrine affairs office wrote in old-fashion Chinese characters on a memo pad, “We’re not Communists anymore and we’re not Kuomintang. We venerate the memorial tablets of both and endeavor to make merit with pure hearts.” Having immigrated here from Fujian and Guangtong [Fukien and Canton] provinces some 50 to 60 years ago, they said they had no trouble in dealings with the recent influx of Chinese from Yunan province because they shared common religious and moral codes. Framed on the wall hung a photo of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee members and the Yunnan Provincial Sec-Gen who came to pay homage on July 6 last year. Not five months prior to that, Foreign Minister Qian Qichen had visited Rangoon and reached an agreement with Sec-1 Khin Nyunt on strengthening economic cooperation.

MANDALAY SIGHT-SEEING

Returning from Lashio the night of December 28, I put up at the Zuifu Liushe, the “Jade Fortune Travel Lodge.” One of a rapid succession of new Chinese-owned hotels to in the ancient capital of Mandalay over the last two or three years. Here in Mandalay, the all-night curfew was lifted in September 1992, but black-outs persist throughout the day. Not to be deterred, the Jade Fortune was supplied with its own generator and the whole building vibrated until the small hours from the tremolo tones of the adjoining karaoke hall. Everything from As Time Goes By to Japanese hits, all sung in Mandarin.

Came morning, I did the rounds of the famous sites. I visited Eindawya Pagoda,where students met to plot independence from the British in the 1920s. The pagoda spire shone brilliant white against the expansive dry-season skies. An old man ambled across the quiet temple grounds shouldering bundles on balance-pole. In August 1988, students, citizens and monks are said to have gathered by the thousands here in this very courtyard. After the General Election, elected representatives prevailed upon the monks to use their quarters for the National Assembly, but word leaked out in October 1990 and the army burst in on the scene. The then-abbot is still in prison. When I to talk to the monks, a pro-democracy sympathizer pulled me aside to caution, “There are Military Intelligence officers in robes among them . . .”

STUDENTS

Throughout the eras, students have always taken the lead in Burma’s political reforms. Ko B is a fourth-year mathematics major at Mandalay University. He participated in the 1988 demonstrations. “After the Election, things in town have gotten better at least.” Tourists reappeared and he could earn occasional money as a guide. “You won’t see me carrying on protesting like that anymore. My graduation got delayed and here I am 24 years old already. I better find work soon .. .” he spoke, just like disaffected students elsewhere. As far as he knew, no anti-government actions were planned for the January 4 Independence Day. “I’m finally gong to graduate this year, but there’s no jobs in this country. I want to go to Australia, where I have an aunt.”

Computer programming student Ma C (22) seemed to take more interest in politics. “If the talk turns the slightest bit political, it’s either ‘Don’t talk to me in such a loud voice!” or they pretend not to hear and run away. Everyone’s so afraid, you’d think the schools were still shut down.” Burma’s secondary schools and colleges were closed anywhere from two to four years. According to her, apart from children of parents with status under the military government, only one graduate in ten can find work. “Most students are preoccupied just thinking about their own future, let alone politics.”

Preferred occupations and employment include gem brokers, university instructors, computer school tutors, translator-guides, and anything overseas. For instance, a computer operator in Singapore earns a monthly salary of US$300. Low wages for over there, but far beyond anything they could hope to earn domestically. At present, it takes $200 a month to feed a family of four in urban Rangoon, while a civil servant takes home an abysmal $8 to $13 a month, making it virtually impossible to live. So even the most aspiring civil servants have to make an “occupational side-business” of their official post.

That afternoon in Mandalay, I located the “Monastic Abbots Training School” responsible for cultivating head monks for temples throughout the provinces. “The industrialized nations are rich in material goods and have high levels of education. But they are plagued with social ills, while the people do not seem to find happiness. Through meditation they can find that something they are missing. Purity of mind, peace, and growth,” pronounced the School’s English language instructor (54). Find this inner happiness, and just maybe you could ignore the insanities of the junta and chaotic economy. “Recently, many Western tourists come to meditate. Perhaps you too would care to . . . ,” he suggested. When I asked whether young Burmese also showed interest in meditation, this former university lecturer replied disheartenedly, “Of course they have house-hold constraints, but really most students just want to talk and listen to music.”

HUMAN RIGHTS OR MONEY

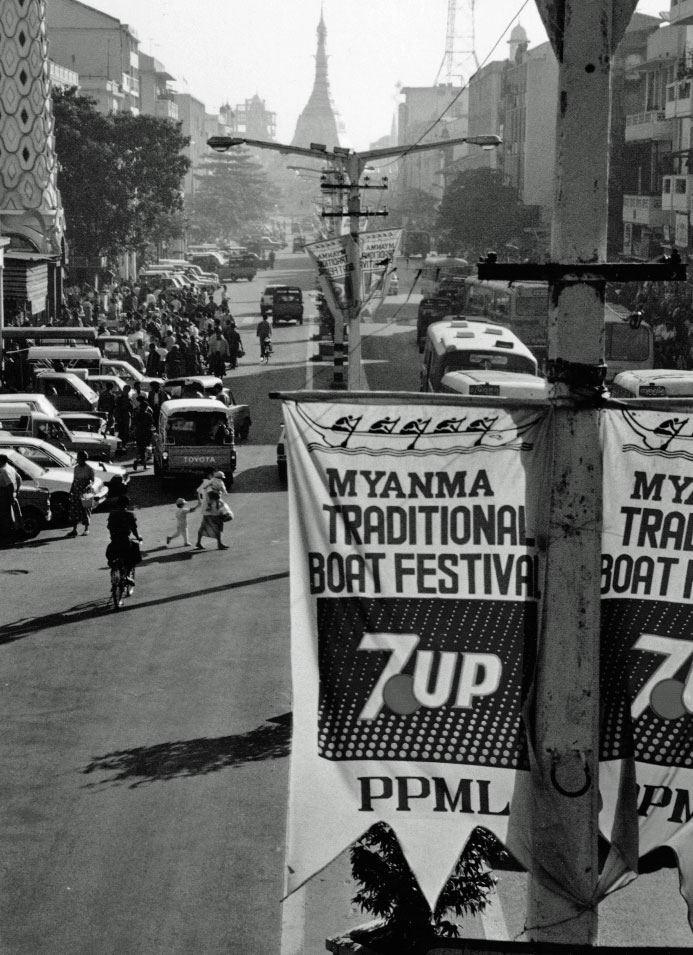

Burma celebrates New Years by the Buddhist calendar, but at the end and beginning of the Western calendar year the military government holds traditional boatraces, Olympic qualifications and other sports meets and visible events through-out the country. On returning from Mandalay, I found all the main streets of Rangoon bedecked with colorful boat race pennants. “The rich people go to watch and the poor people are busy trying to make a living even on holidays, so either way nobody’s thinking about politics. True to the military’s aim to make us forget,” quipped my interpreter. Featured prominently on the pennants was thelogo of the official commercial sponsor, a major American soft-drink.

New Years’ Eve, the day I was to exit Burma. Rangoon’s Strand Hotel, luxury flagship of British Burmah days, now refurbished as a SLORC-English joint venture and reopened this past November as a $200-a-night-minimum five-star wonder was where I arranged another rendezvous with the foreign diplomat I’d met earlier. “American diplomacy toward Asia, as symbolized by the APEC, is changing. My country, too, though we still play up human rights more than Japan. No, the days of all-or-nothing bargaining are over.” Since Than Shwe’s SLORC administration, change has been slow but sure. And that, he admitted, was not a bad sign.

This time, it was he who’d asked for the interview. “Bangkok correspondents are still painting this country ‘pitch black.’ They’re not journalists. Sure, that’s the sort of piece that sells, but they’re acting like politicians . . .” Look carefully, he said, and you’ll see that the situation is turning dark gray. Ignore the changes and keep criticizing, it will only set back what little progress there’s been.

China is the country with the most sway over SLORC. Japan was the first country to lift sanctions after Tiananmen; the US extended Most Favored Nation status to China last June. Moreover, “Since China is far more attractive a market than Burma, you can’t expect either the US or Japan to argue with China. Or rather, both countries are concerned, and rightly so, that if they press on with sanctions toward SLORC, China, its only major ally, will swallow Burma whole.”

For China, eager to industrialize its inland provinces with Middle Eastern petroleum piped straight to Yunnan without negotiating the environmentally sensitive Malacca Straits, access rights to Burma and the Indian Ocean are essential. Reports from Beijing in October 1992 confirmed that China is building at least one naval base at the mouth of the Irrawaddy River.

Indonesia, contrary to wire service pronouncements that they would “bow to world opinion,” openly welcomed SLORC’s diplomatic mission late last year. President Suharto even shook hands with Sec-1 Khin Nyunt. Thailand, moreover, also announced friendly relations with SLORC at the end of the year. “This year, before July 19 at the very latest, America, Australia and also Japan will strike a new diplomacy toward Burma,” my foreign embassy friend predicted. Normalization of ties being desirable both to Burma and the democratic countries, ODA will be reinstated subject to certain conditions. “The junta will make noises. So the International Red Cross and other relief without political coloration will come first, then I guess, the best scenario would see the UN Development Program widen the opening,” he told me, giving me a lift to the airport.

DEADLINE

The July 19 deadline he mentioned was, of course, Martyrs’ Day. The anniversary of founding father Aung San’s assassination, as well as the day marking the full fifth year of Aung San Suu Kyi’s incarceration. SLORC has already indicated that her sentence is to be extended. But with this year’s ASEAN meeting also coming up in July, a sudden concessionary reversal might just well be in the cards. “Next time you come, I’ll explain everything,” NLD Sec-Gen’s Aide Kyi Maung had told me four years ago. This time he was in prison, promise unfulfilled. So again I must conceal identities. I still have of way of knowing just how SLORC would treat persons I might name. “You’re in the same boat, too, you know.” Parting words from a politician after a confidential interview. If once this report gets published I’m able to return to Burma and write using real names, I’ll consider that real progress.