Cambodia Women in Love with CambodiaNovember 2001

At a park in the heart of Tokyo I saw a woman practicing an ethnic dance in the westering sun. The woman, Hitomi Yamanaka (40) from Fuchu City, said, “In Cambodia they perform a dance in their daily life to dedicate it to the god, not to show it to tourists.” Hitomi graduated in classical dance from the Royal University of Fine Arts in Phnom Penh this year and became the first foreigner to graduate in that department of the university. She came back to Japan in October but she will go to Cambodia again before long.

Being attracted by something peculiar to Cambodia like Hitomi, a growing number of Japanese women have lived in Cambodia. The country, however, was badly scarred by the war, and about 70 people died every month by stepping on a land mine laid in the country. Moreover, the country is struck by a flood or a drought almost every year. So Cambodia is still struggling to get out of poverty. Even to have a decayed tooth treated, you have to go to a neighbor country Thailand. Why do the women live in such a difficult place to live in? To find out the reason I visited Cambodia.

Trying to find what they have lost

I met Professor Sam Tiya, a prima donna of the Royal Dance Troupe, in the capital of Cambodia, Phnom Penh. She has a high opinion of Hitomi Yamanaka, who dances as skillfully as Cambodian students do, because Hitomi has acquired the traditional dancing technique, crossing the barriers of language and culture. But at the same time Professor Sam Tiya thinks that Japanese people who come to Cambodia are trying to find what that they have lost in exchange of easy and comfortable life.

Hitomi said as if to endorse Professor Sam Tiya’s remarks, “In Japan you will be frowned at if you don’t act in the same way as others. And there are many nonsense competitions, in which people try to have a lead. They compete even with their neighbors in trifles, and such competitions keep them going. If the competition relates to what they really want to do, it may be worthwhile. But many people don’t seem to know even what they want to do. I don’t like such Japanese society of today.” Hitomi went back to Phnom Penh to take a master course shortly after she met some old friends and cleaned her house.

Mysteriousness is fascination.

“The mysteriousness of Cambodia fascinates me,” said Masako Suitsu (33) from Fukuoka City, Japan. The mysteriousness is not ethereal but sordid and chaotic. Three years ago Masako opened a Japanese restaurant in Siem Reap, where Angkor Wat is located. She is sometimes in trouble over her restaurant’s unfavorable balance and absence of a young waitress without leave. But luckily she has a good cook (40), who used to be an elementary school teacher. “A person who is honest as he looks is nice. But I’m not interested in such a person. Cambodian people, however, seem enigmatic. I can’t make out what they think. That’s the point I’m interested in.” Now I understand why mysteriousness is fascination for her.

Masako used to work as a salesperson in teaching materials of English conversation in Fukuoka, but she went to Tokyo at the age of 23 to work for a TV program production company as an assistant director. But she was assigned only incidental tasks. So she went to a vocational school to learn scenario writing to better herself, but her teacher said her writings would not be sold. She thought she needed to see the world more, so she became a bar hostess in Ginza. She intended to work only for a week but ended up working for four years. She even worked as a geisha in Mukojima at the same time.

Masako said, “In Japan everything is all arranged beforehand and there is no room to step in. If a young man has guts, he will not be able to do anything without money. Here in Cambodia, you can’t tell what is going to happen. But I think life in here rather suits me.” She drew a conclusion from working experience in various fields, and the conclusion brought her to live in Cambodia.

I asked why she chose Cambodia. She said, “Singapore and Bangkok are similar to Tokyo in the sense that they are big cities. So I don’t want to bother to move there and start something new.” Cambodia is not firm, in other words, it is still in the process of development. She said that she wanted to see with her own eyes how the country was changing and how hard the Cambodian people were trying to change their country as well.

On the outskirt of Siem Reap you can see water buffaloes and palm trees. Here time passes slowly just like the water of a paddy field does. “This scenery gives us peace of mind,” she said. The pastoral landscape in Cambodia pleases her. So she named her restaurant ‘Sanctuary 36.5℃’, combining a word ‘sanctuary’ with a meaning of a safe place for refugees with 36.5℃, which is the normal body temperature.

Against her original intention of a several-week stay, Kazumi Akao has stayed for more than four years

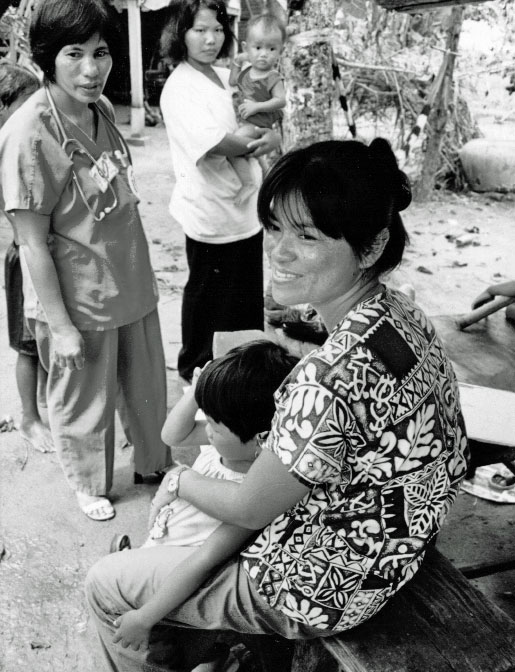

Kazumi Akao (39) from Matsudo City, Japan, is a customer of Masako’s restaurant. She is a nurse working for the Angkor Hospital for children. At the request of the American director of the hospital, she came to Cambodia to help him for several weeks. But she has stayed for more than four years since then. She told me about her experience during the first week of working here. “I was surprised to see a lot of ants gathering around glucose drip. I told it to a Cambodian nurse. Then she said, ‘What’s wrong with it? They are just ants.’ I was so shocked that I wanted to go back to Japan,” she said, looking back at that time.

Her main task here is to train Cambodian nurses. She makes the rounds of the homes of a malnourished or infected child with the nurses. She has a US nursing license and also she has experience of working at hospitals in Tokyo and Hawaii. She continued, “But I came to think that dealing with the huge gap in the ideas of sanitation would be very challenging. Now I feel it worth living to find out feasible methods for nursing care in this country.” She explained why she had stayed in Cambodia for such a long time. She has no intention to go back to Japan for the time being, because she is afraid that she might not put her heart into her work in Japan as she does now.

A man who tells off

The Japanese tourists who visited Siem Reap exceeded six thousand last August. Naoko Aoyama (27), working for a Japanese-affiliated travel agency in Cambodia, has been busy with taking care of group tourists. She is from Higashi-murayama City, Tokyo. She used to work for a computer company as an office worker in Japan. “I find fulfillment in my present work, which I hardly got in Japan. And the greatest find I made is a man who has the same value as mine,” she said with a cheerful look. The value she means is that they don’t work just for money. A monthly salary of a local employee is 1,000 US dollars at most. It’s a small amount considering prices in Japan, but it’s enough to live here.

Naoko got married to Soeung Sochia, a tour guide four years junior to her, last May and lives in his parents’ house. Naoko said, “Japanese men whom I dated were too gentle to depend on. But Soeung ignores me or tells me off when I act willfully.” On the other hand, guessing the reason why Japanese women come to Cambodia including Naoko, her husband Soeung said, “There are a lot of things we want to do but we cannot do in this country. However, we Cambodian are trying hard without giving up hope. Maybe Japanese women like such toughness, I think.”

Learnning from their toughness

The first Japanese woman who came to live after the Pol Pot regime ended was a worker for Japan International Volunteer Center (JVC), a pioneer of nongovernmental organizations. The JVC Phnom Penh Office was established 15 years ago. The chief Yukiko Yonekura (41) said, “In Japan the people seem happy, but still there are not so many things that touch the people’s heart. The Japanese people hardly need to worry about food or hospital. But I find myself happier here in Cambodia.”

I asked Yukiko, who volunteered to work in Cambodia, to explain the mental process of Japanese women who got to stay in this country for a long time. She said, “Most of Japanese visitors come, imaging that the Cambodian people are poor and incompetent. But soon they find the Cambodian people living happily without being overpowered by the death of their family or friends. The Japanese visitors are surprised to see that the Cambodian people are much tougher than the Japanese people, who feel down about the recession. Once they realize it, they feel like living in this country, I think.”

Activities in character

Through the French style window a breeze carrying the clamor of the market is blowing into the room on the second floor of the Japanese restaurant. Masako said, “I have fully realized that I’m here because I did choose. In Japan I had been considered strange and odd from my childhood, but I don’t think I gave much trouble to anyone. I felt very bitter about working in the office where my personality was rejected. But the people here are all odd, and they do their work in character with them. Nobody here says I’m an odd person.” She said she would not go back to Japan yet, because she still had to brace herself to go on.

I had sent Masako two kilograms of spicy Mentaiko, the marinated roe of the pollack, which is the special product of her hometown, at her request by E-mail, but there was no dish with Mentai on the menu of her restaurant. She keeps on writing a scenario at nights and the scenarios in stock seem to become more interesting by adding spice from her hometown.

Note:The number of the Japanese people staying in Cambodia is 453 including 163 women in 2000; 559 including 213 women in 2001; 655 including 286 women in 2002. The number has increased at the rate of 100 people a year and the proportion of women to men exceeded 40 % last year. = from the survey of the Japanese Embassy in Cambodia.