Thailand Backstreets of ThailandAugust 1988

ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THE RAPID MODERNIZAION

I was surprised to visit Suample Slum in Bangkok, Thailand’s capital, after eleven months. A pond about the size of a ballpark that used to smell badly withall kinds of garbage and waste… like plastics and dead bodies of animals … floating on it was now completely covered with new shacks.The population of Bangkok is about 6.5 million. Some 1.2 million of them come from the country towork and are living in such slums.

I wandered around the narrow, maze-like alleys made of planks laid on stacks. From among the almost incomprehensive hum of vice speaking in Thai, I heard someone call a Japanese-sounding name,”Shigeru, Shigeru!” In a dark room with just aray of the tropical sunlight coming in from a small hole on the corrugated iron roof, Ohon-Shee Ruchaisaa, a young girl of 22, was soothing a fretting baby.

The fact is that Shigeru is not her child. He was born to a Japanese-bar hostess called Sriphone, 17, and one of her customers. Sriphone could scarcely support herself and implored Ohon-Shee to take care of her baby. She said OK because “I felt so sorry for Shigeru.”

Ohon-Shee is no better off herself. It was probably impossible for her to buy expensive powdered milk; in the baby bottle was some watered condensed milk that day. However, Ohon-Shee looked quite happy. “I want to give him good education and to bring him up so that he will be able to go to Japan to look for his father.”

As many as 340,000 Japanese tourists visited Thailand last year. This summer Japanese businesses’ investment is coming up to 40 percent of all foreign investment in the country. In the back streets of the country which is now going through rapid modernization, there are thousands of girls like Ohon-Shee. Her odyssey is reported in a series of columns.

POVERTY FORCES THE SISTERS TO GO ON THE STREETS

Ohon-Shee, 22, went on to talk while splitting a board of wood with a hatchet to make a fire in a clay charcoal stove.

She finished elementary school in the northeastern village of Nhon-Pranooi 12 years ago. She was ten years old then … elementary education was four years in those days. The eldest daughter, she had taken care of her brothers and the housekeeping since she was six years old. She carried water on a pole on her slim shoulders for one baht (about 6 yen) a pole, bringing her family an important cash income. But five years ago, after going through days with only soy sauce to eat, she left her village for a better job in the city.

Now she lives in a rented room of about six-tatami size with her brotherSompyet, 19, two of her sisters Pompen, 18, and Somudi, 16, and the ten-month old Shigeru. Pompen and Sompyet followed their older sister the next year Ohon-Shee came to Bangkok, and so did Somudi last year. The three sisters got a monthly pay of 900 bahts on their first jobs at a cheap restaurant. Unable to send any allowance to their family in the village on that income, they chose to go on the streets. Now they earn an monthly average of 3,000 bahts, sometimes getting as much as 5,000… a substantial amount considering Sompyet, a construction worker, gets only 1,700. Prostitution is the only way for the elementary graduates to get as much as a college graduate.

Their mother came to visit her children the day I visited Ohon-Shee. Bumpen, 41,complained about the village life. “With the draught and the floods, we could barely crop from half of our planting and we are even buying rice for our own meals. Our buffalo broke his leg in April and we ran into a 5,000-baht debt. Our old house is falling down because of termite, we’ve got to built a new one.”

The supper was ready. Ohon-Shee looked bashful at my compliment on her cooking. After the sunset, the three sisters got up for makeup.

“THIS IS NOT THE JOB I LOVE TO DO.”

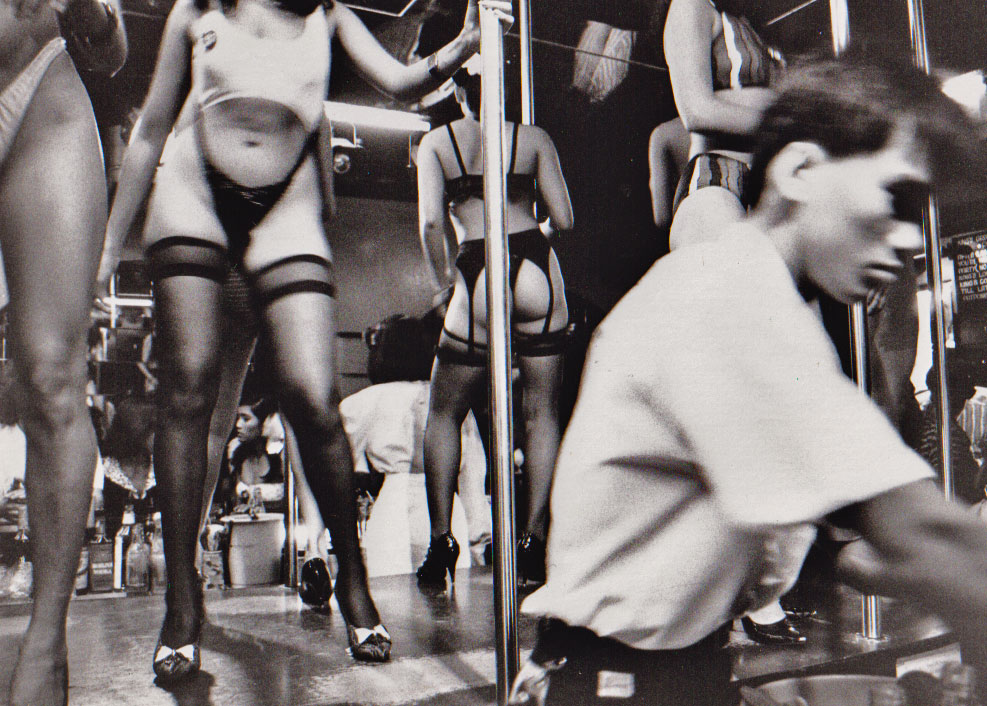

Ohon-Shee, 22, and her two younger sisters work in one of the go-go bars which floods Pappong Street, Bangkok’s amusement center. Next on the east side is Thanya Street, which is lined with Japanese-style night clubs and Karaoke barson both side.

Lights of loud colors was shining on the almost nude, fresh bodies of young girls. No Thais were seen among the customers. In the ear-splitting sound of music, the girls earnestly spoke to their prospective customers in broken Japanese and English.

All of a sudden I heard bottles break with a crash. I looked back and saw a bunch of furious girls drive out one of the customers. One of them told me that he had gone violent at an indirect refusal to his proposal for a date. Although usually hidden under their heavy makeup, the girls’ pride bursts out into rage sometimes.

“I’m not good-looking and now I’m rather old, I can get at most five or six customers a month,” said Ohon-Shee. Since they are not extremely popular, the three sisters can’t shun all disgusting men. “This is not the job I love to do. You must understand everybody’s got their own reasons.”

Some 40 girls of fifteen to mid-twenties belong to the go-go bar. There is no monthly pay; customers directly pay them 500-1,000 bahts.

A song of popular Thai band Krabao goes, The government emphasizes tourism To get foreign currency And everybody knows who the biggest earners are The girls living on Pappong Street.

Ohon-Shee didn’t get a customer that night. “When I have saved 10,000 bahts, I’d like to run a drugstore back in my village.” But with most of her money spent on the allowance for her parents and on her own living, she was not sure when her dream will come true.

WORKING AWAY FROM HOME: WHEN WILL IT BE UNNECESSARY?

The car ran eleven hours from Bangkok to the village of Nonpranoi, Sakhon-Nakhon Prefecture, near the Laotian border. It was the rainy season, and the whole farming village was busy planting rice seedings.

I met with village deputy chief Prabaan, 44. Out of 756 villagers, nearly two hundred youths were away. “We got electricity here ten years ago. Since then TV has been carrying off young people from here,” he said.

An overwhelming majority of the young people who left the village work in Bangkok. The money they send has enabled 70-80 percent of the village households to have a TV and an electric fan. There is the same flood of ‘made in Japan’ ranging from motorbikes to MSG here as in Bangkok.

“As ever we still can do nothing about floods, but earlier when some of us didn’t have enough rice to eat, others would lend them some of theirs. Now people are always calculating how much the rice they lend should cost and all. It’s harder to live here.”

I wanted to visit Nonpranoi elementary school Ohon-See and her two sisters graduated from. I met Mr. Prasaht, 38, who had been the now 16-year-old Somudi’s class teacher. “She was a chairperson of the pupil council and went on to high school with the very best grades of all the seven schools in this parish.” He could find no words to say at the news about Somudi.

Those who entered Japan from Thailand totaled 31,163 for last year. The Immigration Office says that as many as 16,175 of them were admitted into Japan for short stays on the purpose of “sightseeing.” Many of them came to work for good pay.

On the plane home, I sat next to a group of three young Thai women. “For sightseeing,” they said. The three girls naturally reminded me of the three sisters, creating a kind of double image to my mind.