Cambodia Behind the SilenceJanuary 1991

Rubbish is the staff of life

“While I sniff this, I feel as if treading on air. I even feel I’ll be able to get a star in the night sky. Besides I can get hunger off my mind.” At around past nine in the capital of Cambodia, Phnom Penh, a street urchin. Te Biasuna (12) was sitting on a stone bench with his head back after his daily routine. He was sniffing glue in a plastic bag. He said, “Why, I shouldn’t do this? I’ll not stop it.”

I followed Biasuna’s day. His lodging for the night was a small space in a closed stall, between a table and chairs under a plastic tarpaulin. He went to sleep around two o’clock in the morning when the stall was closed, and came out from under the tarpaulin sluggishly near nine o’clock when the sun was coming high. After he washed his face at a fountain in the park, he went to the market. Although he earned nothing yesterday, he could eat breakfast free here. He found leftover rice gruel in a bowl. He scratched his head, feeling embarrassed at people’s eyes, while he took up the bowl.

After he filled his stomach, he started his “work.” He was lucky today,because he found a gas range among the rubbish at a shop front. Small though he was, less than 130 cm in height, he carried it on his back to a junk shop. In Cambodia 1kg of scrap iron can be sold at about three yen and 1kg of copper at as high a price as 120 yen. I heard that scrap iron was sold in Thailand and rubber was converted into elastic strings within the country.

Biasuna gained about 60 yen from this. “10 % of waste materials are brought by children. 20 to 30 children come in a day,” said the shop owner Von Virak (25). According to him, children bring him waste materials they collect such as metals, plastics and rubber that can be exchanged for money, even if for small money. I visited a rubbish dump called “Hope River,” Stung Minchey in Khmer. The foul odors of rotten fruit and smoldering vinyl assailed my nose. The rubbish was smoking because of spontaneous combustion. When a dump truck arrived from the city, more than one hundred people rushed toward the truck, and more than half of them were children. A boy, who was rummaging about in the knee-deep rubbish heap, picked up a soot-covered lump of plastics.

Seven swift years passed after Cambodian economy was in UN boom. After the boom, the Asian Bubble burst and foreign investments, Cambodia’s only hope, have decreased sharply. The GDP per capita of this country has been held at 300 dollars in check. In Japan, the GDP of which is 130 times as high as that of Cambodia, there is a rubbish problem and recycling is now its urgent issue to be solved. On the other hand in Cambodia people are suffering from poverty because there are no developed industries and rubbish itself is the staff of life for the people.

Drugs ruin homeless children

I heard that one out of fifty were street urchins in the capital of Cambodia, Phnom Penh, at present. The Ministry of Social Welfare estimates the number of children living on the streets is about 20,000 in the capital with a population of one million-odd. And drugs give an additional blow to those homeless children.

Not only questionable adhesive agents that are made secretly for sniffing and labeled as gum adhesives but also amphetamine-type stimulants such as “Yama” or “Yaba” are imported from Thailand, and they have come into wide use among children and young men. A deputy bureau chief of the narcotic control police, Loa Ramin, said, “At first children sniff glue to get hunger off their mind. Taking advantage of it, gangsters make those children drug addicts to force them to commit illegal acts such as prostitution or theft. It’s a nationwide phenomenon now,” He told me candidly. The narcotic police seized 111 kg of heroin, 31 kg of amphetamine and 80 tons of marijuana, and arrested as many as 340 people in the last five years.

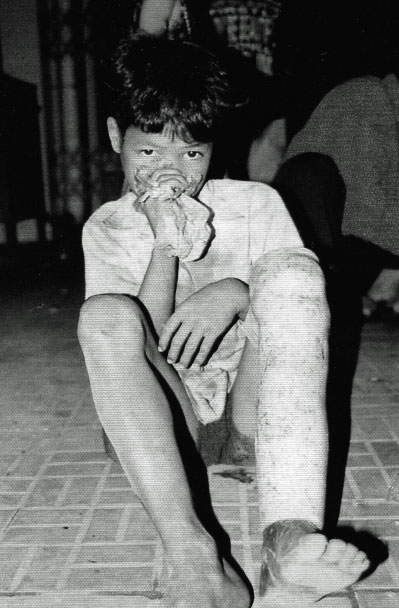

I went along with a member of a local NGO “New Family” on night patrol. At 8:30 an advisor Im Sorein (27) found children sitting in a circle on Monivon Street in the central part of Phnom Penh. He ran up to them with a first-aid kit in his hand. Among them, there was a boy who lost his lower leg by explosion of antipersonnel mine. He was also sniffing glue, but Im Sorein didn’t take it away from him. Instead he gave him treatment for scratches.

In spoke to the children, giving some candies. “First we have to make friends with them. Then we give them medical treatment. Our aim is to make them learn a trade and stand on their own feet. But it takes a lot of time,” he explained. They provide food, clothing and shelter for a child who wants to come to the care center, and send him/her to an elementary school. Every NGO is working on rehabilitation of children whose mind has grown wild because of poverty and drugs. The rehabilitation training includes counseling and traditional performing arts such as Khmer dance. But he also mentioned that quite a few children went back to the streets before finishing their work training for self-support.

Kon Karn (13) is in training for drug addicts at a rehabilitation center of a French NGO “Goodo.” His parents are divorced. He is the oldest of four brothers. When he had lived on the streets, a broker took him to Thailand. Kon told me of his experiences.

“The broker said I could earn 3,000 baht a day, so I went along with him to Thailand. But I was forced to be a beggar and got only 1,000 baht in all.” Last year he was taken into protective custody by Thai Police and repatriated enforcedly. But before that he had already crossed the border four times. “I want to go again,” he said without caring about the advisor’s ear, “Because there is plenty of food. I can even eat nice cake. I may sniff glue again someday.” To the children who are eager to get out of hunger and poverty as soon as possible, to earn a daily cash income seems a shortcut to it.

Parents grew up in the civil war era

You can see many children working in this country, if they are not street urchins. They work to help out with the family budget. Chum Roon (12) came to Phnom Penh with his family three years ago. All the family, his parents and six brothers, work in a brickyard. He attended an elementary school only for one year. “I’m worried about my children’s schooling, but we can do nothing but this, because we can’t find another job,” his mother Om Funny (41) explained.

Some girls of war orphans or abandoned children are forced to be prostitutes. The number of girls who were relieved from brothels in the last two years amounts to 610. Titto (fictitious name, 15) was tricked and sold to a prostitution broker by her acquaintance half a year ago. “If I resist,I’ll be beaten with a belt. It scares me. That’s why I do as I am told.” She is forced to sell her favors to more than ten men a day. Still, her salary is only 5,000 yen. “Even when I have menstrual pains, I work with cotton inserted,” she said. She also said she doesn’t have time to have lunch, let alone a day off.

Meanwhile Biasuna who lives on the streets has parents and three siblings in a slum. What his mother Mac Bon (37) said was the last words that I expected from a mother. “I don’t care if he doesn’t come home. I don’t think he wants to study.” His parents peddle ice creams for three yen each. They got married at a refugee camp near the Thai border and tried to settle down in a farm village according to the U.N. refugee’s return program. But they couldn’t make a living there, so they came to Phnom Penh.

Sool Village of Battambang where Biasuna’s family lived is in the middle of a paddy region about two hours’ drive on a bad road from the national road. Along the main road, but a narrow road passable just for one car, the original villagers have their residence, and the returnees from refuges are plowing the lands in the back region following the path between rice fields. A farmer, Doon Prun (34), who was having supper with his family in a nipa-thatched hut, said,”In a bumper year for crops we could have a yield of 20 tons, but this year we had a yield of only two tons. A large number of people went to Phnom Penh or Thailand. But we will not go, because I can manage to support my family somehow.”

In Cambodia infrastructure takes precedence over others and a budget for social welfare is only 1- 2 % of the total. The Vice-Minister of Information, Khieu Kanharith, hopes that agrarian culture will make up for what the administration cannot do. The idea that townspeople are selfish is common to all nations, but Cambodian adults in a community of rural districts teach the children manners and means of survival. I am counting on those traditions.” The generation who are in their parenthood now grew up in the midst of the more than 20 years’ civil war and didn’t get enough education at a community or an elementary school. This is also a disaster of war, which drives children to tragedy.

In a border town Boipet people who couldn’t make livings within the country formed a slum. When I left for Aranya Prathet in Thailand, a former soldier with an artificial leg and a child holding a naked baby in her arms held out their hands to me. This border makes a clear distinction between Cambodian economic conditions and Thai economic conditions. There is a sevenfold gap in economic power between the two countries. A factory worker’s salary in Cambodia is about 700 yen, while the counterpart in Thailand is more than 5,000 yen.

After I entered Thailand, I met a governor of Sakeo Prefecture, Nabin Kantahiran. “We’d like to help them. In their country they will not get a job unless their farming is developed. Their coming to our country to work is unavoidable.” To my surprise, his remarks were generous. When I happened to look back at a jungle on the border, I saw a Cambodian with a basket on his head pushing his way through the grass, trying to enter Thailand illegally.