Burma(Myanmer) Under the Military RuleJanuary 1989

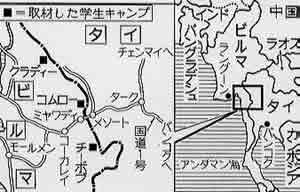

Four months have passed since the Burmese-pro-democracy movement was sunk in a “bloody lake,” Saw Maung’s junta unexpectedly invited foreign reporters from Bangkok to Rangoon and to a few other provincial cities for three days, from January 18, 1989. It also permitted those newsmen to interview the anti-government students who had surrendered and been returned from the Thai border. In this way they emphasized their stability. However, more than 7,000 Burmese students escaped into the jungle near Thailand. They remain committed to fighting against the junta, in cooperation with the Karen ethnic minority. The tension between the students and the military government that demands they surrender by the end of January is very intense. I visited three camps on the border.

JAPANESE AID GOES FOR BULLETS

On January 14, 1989, the sound of frequent shelling welcomed me as I approached Klady Village from the other side. It lies 120 Kilometers north of Mae Sot alongthe Moei River. I had heard there was a student camp in the vicinity.

Waiting for the shelling to stop, I crossed the river. Even though it had lessened, shells still exploded every three minutes. Not only the ears were affected but also the feet. The earth trembled from each concussion.

As I unconsciously ducked every time a shell landed near the trench, 207th Regimental Commander, Zaw Zaw (22) of the All Burma Students’ Democratic Front (ABSDF) informed me, “The government troops began to bombard yesterday,(January 13). They are firing from 12 Kilometers north of this camp.” He pointed to the steep mountains thickly covered by tropical trees. Here, Klady Village of Karen State, is in the emancipated region of Karen National Union (KNU), the main element of the National Democratic Front (NDF), a coalition demanding rights for the ethnic minorities of Burma.

According to ABSDF chairman, Htun Aung Gyaw (35), whom I met secretly last nightin the town of Mae Sot, more than 7,000 students have sought shelter in the jungles on the Thai border, joining with the NDF in the hope of democratizing their motherland. This represents at least ten percent of all Burmese students. Well over three thousand of those are in five camps in Karen state, and the others are in camps dotting Mon, Karenni, and Kachin states, or in a few groups on the Bangladesh and Indian borders, he said. About 2,100 students have already surrendered because they couldn’t bear the severe conditions in the jungle, Bangkok Post reported on January 17.

“There is no way I could ever trust General Saw Maung’s word the military won’t charge us with some crime if we surrender by the end of January. We will stay here until our country really has democracy,”Chairman Htun Aung Gyaw said. He himself had been imprisoned for four years and eleven months during Ne Win’s reign, and he doesn’t mince words at all.

“The 230 students of Klady Camp, with incessant shelling coming closer and closer, live in a trench 50 meters long and two meters deep dug along the Moei River. Their 207th Regiment has only 35 old rifles. Thirty students at a time take the guns and go to the front line in shifts leaving the other five rifles at the camp.

“They must have used Japanese aid money for bullets and shells.” These words from a lean young Burmese student went straight to my heart. When I peered out of the trench during the incessant bombardment, a platoon of seven soldiers wearing camouflage uniforms and bullets, shouldering a shining American rocket launcher, appeared suddenly. The students surrounded them and watched how skillfully the Karen soldiers located the government troops’ position from their scouts by radio and aimed using a compass and graduator. Whenever a rocket vanished into the blue dry-season’s sky with ear-splitting metallic sound followed by a tremendous blast, the students applauded.

Saying,”The government will make a counter-attack soon,” the platoon commander urged me to run to the landing place on the Moei River. There was not a living human being in the houses lining the street. Echoing through that ghost village only the bombardment and the sound of my footsteps could be heard.

REWARDS FOR STUDENT HUNTERS

It was now four days after I left the student camp in Klady Village on the Thaiborder after the Burmese government’s shelling got closer. In a refugee camp located in a valley five kilometers inside Thailand from the Moei River which forms the border, I came across the same ABSDF students whom I had just met under fire four days before.

The students wearily got off a large crowded truck. They had virtually nothing but the clothing they wore. All seemed worn out as a result of their long stay in the trenches. No one carried a gun. I asked,”Where are you going?” The regimental commander, Zaw Zaw, softly replied that they had had to retreat before the government’s fierce attack and to escape to Thai territory.

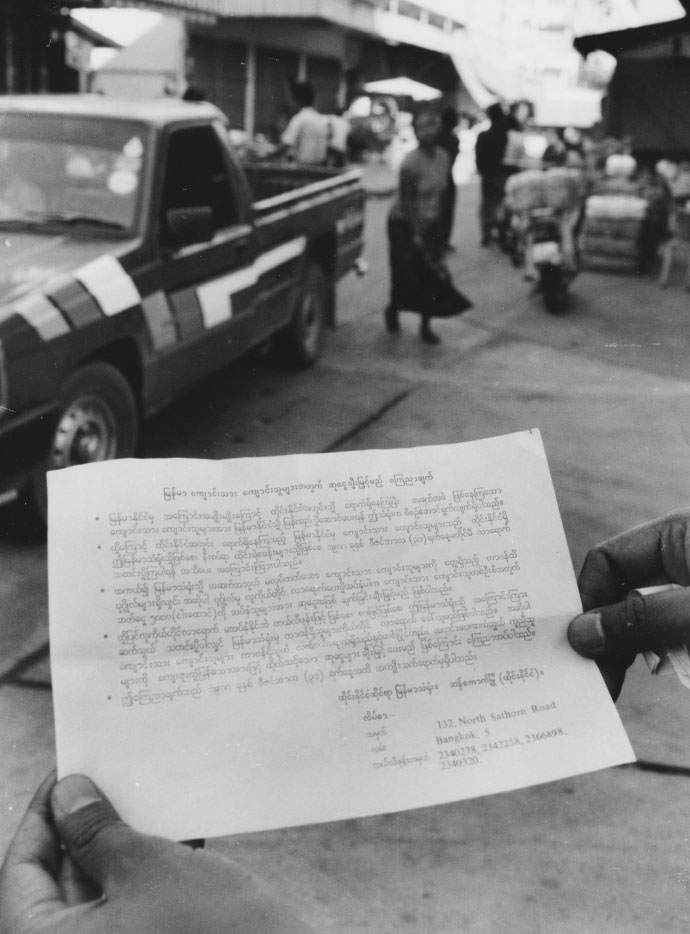

The students often have to go back and forth across the border but even in Thai-land they are not always safe. “If you took a student to Burmese Military Inte- lligence, they would pay you 5,000 baht (about 30,000 yen) for him.” After having heard such rumors, I got first-hand evidence, in the form of a hand bill.”Rewards will be given for Burmese students!” was printed in English and Burmese on both sides of the paper, and at the end of the message there was the phone number and address of the Burmese Embassy in Bangkok to contact. “Student hunters” wait for the students escaping to Thailand. Based on the agreement between General Chavalit of the Thai military and General Saw Maung of Burma, 320 students have already been repatriated from Thailand sice last month (December, 1988).

Students are not the only ones to take shelter on Thai territory. Although the Thai government opened this refugee camp several years ago for Karen civilians, its population has rapidly expanded recently to 5,779. During the last three months a thousand people, including five hundred from Klady, the village mentioned earlier, have swelled the camp in the valley. They are rudely sheltered in makeshift barracks densely crowded together.

A 44-year-old high school English teacher from Karenni territory who arrived here on the 13th spoke to me in fluent English, but asked,”Please don’t write my name, because we will be arrested if Thai authorities find out we are not Karen civilians.” He continued angrily,”I will take up a gun against Saw Maung. He killed my innocent students when they demonstrated for freedom.”

Nineteen years ago, this teacher had been a government soldier, but he had retired in disgust at Ne Win’s policy of suppressing the minorities. He then taught at a country school. Now he has decided to take up a gun again as a soldier against the brutal Burmese government.

HERE SOLDIERS ROT BEFORE THEY EVER FIGHT

Each of the three student camps along the Thai border has its own “field hospitals.” Despite the appellation “field hospital,” all the beds are filled with students suffering from malnutrition and malaria rather than from wounds from combat. Search the wards and you find students shivering from fever or retching from malaria parasites. In one of the hospitals there was an elementary school classroom under the same roof, with children reciting their lessons separated by a thin bamboo screen from the patients.

On the 15th, I met Soe Po Gyaw (22, fictitious name), a student of Rangoon Medical School who was hurrying between beds at the field hospital of the Thay Baw Bow Camp. Although it was so hot that the finder of my camera was blurry with dripping sweat, patients were shaking from 104F. malarial fever. Soe Po Gyaw and Dr. Poe Tet Pyn (28, fictitious name), a veterinarian, treat an averageof 20 inpatients and 60 outpatients everyday.

More than eight hundred students are in this camp. Although the three hospitals are full of malaria patients, there are just five medical students and only two doctors. “They are out of our hands. Could a Japanese doctor come and see them?” Soe Po Gyaw asked.

It has already been five months since they fled to the jungle. The Karen National Union (KNU) shares out some rice with them, but the students can manage to have only two meals a day, without any side dishes. The climate is very difficult for them as well. The camps are in the mountains where the temperature change between noon and night is extreme. It is often too cold for sleep at night, especially since the students escaped with nothing more than the clothing they had on. Daily their physical strength decreases because of malnutrition. There was a frost this New Year Day and two students with open-necked shirts and longyis (Burmese sarongs) froze to death. Some “student soldier” break down before ever fighting, but they don’t lower their guard against the government’s demands to surrender.

Swe The (21), a vice chairman of ABSDF pointed out a significant announcement inThe Working People’s Daily, the only daily newspaper in Burma. It was a funeral announcement in the December 31, 1988 edition and read: “Memorial Service for Maung Chew Sei (21, fictitious name) will be held at such and such temple, 13:00 on January 1st. Chief mourner, So and so.”

Maung Chew Sei was one of the first 91 students flown back under the Burma-Thai joint repatriation program. This article was a clear message from his bereaved family, using an advertisement form in order to evade the strict censorship of news. The newspaper had been delivered by his elder sister, Miss Tin Tin Oo (fictitious name), who had disguised herself as a trader. According to her, Maung Chew Sei had been arrested and imprisoned immediately after his arrival at Mingaladon Airport in Rangoon. He had been tortured, and, although he was later released, he was so emaciated that he died on December 30th.

“There is another strange story,” the vice chairman, Swe The continued. He said that the first group of about 50 students who had surrendered to Rangoon on foot on November 18th became missing without ever passing the two checkpoints of an anti-government organization. Also out of the 1,800 who had surrendered and walked back through the jungle, he hasn’t heard of a single one arriving safely, according to his underground connections.

REAL FIGHTING HAS JUST BEGUN

While covering the military exercises in Kawmoorah student camp on January 16, I got a surprise. The man teaching the students how to deal with grenades in a trench was a white soldier. He pointed to his right arm when I asked his nationality. There was a patch of the West German flag on his sleeve.

“Could you let these young men die before your very eyes? To give only guns tonhasty students means to let them commit suicide when they face the regular army.” He introduced himself as an ex-warrant officer of the West German army, Hening (36). He comes here during his vacation every year with an ex-serviceman friend. He has fought against the Burmese army. He explained his motivation as “sympathy with the Karen who had been fighting against the junta without help for forty years.” However, this sort of foreign support is the great exception.

How do the Karen see the students, I asked. “There are many sorts among the students. Although we have already fought for forty years, they have been here only four months. The tender-minded students, those who came because their friends came or those who thought the border area would be an easier place to get foreign aid, those are falling away. I’m afraid for them, but we can’t detain them. In fact, the fighting has just begun …” Mr. George Crayton (38), KNU’s director in charge of student support, analyzed coolly.

“We certainly aim at democratizing our country, the same as the students do; we don’t seek independence of each ethnic minority race. But to be true democracy, the rights of all minorities must be guaranteed.” Colonel Thula (56) expressed KNU goals. But the colonel also spoke to the point,”The profits from the teak that Japanese trading companies buy is being diverted to war funds. Please tell Japan’s government it’s necessary not only to suspend aid but also to impose economic sanctions against the junta.” He was commenting on the headline news story reporting that “Japan Suspends AID for Burma” which he’d read in a Thai Paper, The Nation just before our interview.

The Karen I interviewed had an impressive kind of composure that comes from forty years’ experience resisting the Burmese government. The students, on the other hand, driven into a corner and trapped on the border, appeared perturbed and uneasy. They sent a hand-written letter signed by ABSDF to U.S. President Bush and Vice President Quayle just before the inauguration. They appealed to the U.S. government over the Burmese government’s brutality and closed their letter,”Don’t let the government kill us. Take action right now please.” It seemed like a scream from students begging to be noticed by international opinion.