Cambodia Just Before the Peace TreatySeptember 1991

FLOOD

Although I had expected Khmer smiles, reflecting the mood of the coming peace, mine was the arbitrary conjecture of a foreigner who didn’t know the realities weighing on their minds.

“Where can we land?” Beneath us there was only a huge lake with no ground at allas our landing wheels were lowered below the wings. This was the tremendous flood that had merited only a small article in the English newspaper.

“Houses were washed away and only the tall trees left above the water’s surface. On a hill a number of villagers had evacuated to, a pregnant woman faced a complicated delivery. With no emergency transportation to get to a hospital, she died with her baby still inside.” Mr. Khieu Sok (48), chief of Takeo office of the Cambodian Red Cross reported her death the next day on his return from delivering a hundred tons of rice to Takeo city. He said it was the worst flood since 1953, when he was just a boy. In Takeo alone twenty-three hect ares of rice paddies were under water. Only in Takeo one thousand five hundred families — eight thousand eight hundred twenty-seven people — had lost their homes and been forced to seek refuge in nine public schools and temples.

Although the exact number of victims could not be known because the flood had worsened already inadequate telecommunications and transportation, more than four hundred thousand people had certainly lost their homes.

Seven hundred emergency kits containing mosquito nets, blankets, and vinyl sheets were donated to Takeo by the International Red Cross. “The government hasn’t given even a riel,” Chief Sok said with an intense look. “The people need clothing, medicine, and rice seed. Let me take you by truck to the serious spots so you can please inform the world of this catastrophe!”

“I heard over the radio that Japan gave us emergency aid for this terrible flood,” Phu Kim Bok(29) explained, sitting proudly in front of the wall-length mirror of the newly-opened Tokyo Beauty Parlor. “I named this shop in commemoration of the reopening of diplomatic relations with Japan.” The shop is locatedon the main street of the capital, Phnom Penh. A permanent there cost two thousand riels (100 riels was equal to about 12 yen at the actual rate). This parlor was averaging more than ten customers a day and employed three beauticians.

Their salaries amounted to thirty percent of the gross earnings. The nine assistants got monthly wages of eight to ten thousand riels each. According to one of the assistants, Miss Ho Khon (24), the most fashionable hair style in Phnom Penh was short with a savage perm. The parlor didn’t reflect those sixteen blanks years when the country had been virtually closed to the outside world.

FREE MARKET

Monorom Street, where Tokyo Beauty Parlor was located, was virtually bustling with Japanese motorbikes and beggars carrying their babies. Although lots of people didn’t have enough food for their evening meal, there was a steady flow of brand new Benzs and BMWs. Five years ago, this street contained only bicycles and cyclos and the only traffic light in the country was often dead.

The People’s Republic of Cambodia changed its name to ‘State of Cambodia’ in January 1989. The country adopted a market economy in November of the same year.The state shop where foreigners bought goods for US dollars has vanished. Now anyone who has money can buy anything in private shops, from Johnny Walker Black Label to a Honda Civic. The rationing system for government employees has been abolished for all daily necessities except rice and petrol.

I checked the prices of various items at stores and restaurants in Phnom Penh. A kilo of quality rice costs 400 riels; a kilo of sugar, 240; a pair of trousers, 1,500; a pencil, 20; Japanese color film, 3,000; a 14-inch black and white television (made in Vietnam), 77,000; a Japanese 50cc motorcycle, 880,000; a new Japanese car, 1,600cc, 7,700,000. A two-bedroom flat which had been built in a residential area in Sihanouk’s time costs 6,200,000.

Mr. Keo (40) who works for the Ministry of Social Welfare only earns fifteen thousand riels a month. Because he’s a government employee, he doesn’t have to pay his house, electricity, or water, but he says he still needs sixty thousand riels a month for his family of six. His wife can earn two thousand riels per dress by sewing at home. By using his second-hand motorcycle as a taxi, his younger brother can get about a thousand eight hundred riels every evening and more than six thousand on Sunday.

State factories have also been privatized. The net profit (US$) of the biggest private companies are: tobacco, 1,100,000; whiskey, 210,000; soft drink, 180,000; machine repair, 136,000. The total for the top nine companies is only $1,776,000. Even though each is a major company employing more than a hundred workers, their earnings are no more than that of Japanese household industries.

By the end of August, seventy foreign companies had made contracts with Phnom Penh government. Eighteen have already begun business, and five others, including a Laotian company to provide drinking water, a singaporean hotel corporation, and an American construction firm, have opened offices in Phnom Penh.

I doubted my own eyes when I picked up a copy of Prochachanh (The People’s Newspaper) at the post office. The front page carried an interview with Prime Minister Hun Sen, but scattered throughout the pages were articles promoting ties with American constructing companies and many advertisements for the products of private companies. I was confounded by an ad for an “aesthetic salon” with before and after pictures of a Khmer lady.

The government television station, TV Kampuchea, has modernized their studio with Sony, but it doesn’t seem to be losing any money. Every evening it broadcasts thirty minutes of commercials such as a Kawasaki motorcycle shop, “Tokyo Company,” and Midana Food’s instant noodles.

AGREEMENT

Since Hun Sen and Sihanouk meet at the First Peace Talk in Paris in December 1987, the inclusion of Pol Pot’s party in the Supreme National Council created many quarrels and points of contention, such as how many seats would be alloted for each party, who would be chairman, and how much each army would be reduced.

Just before the second official meeting, which took place on August 27 this year in Pattaya, Thailand, a western diplomatic source revealed that there had been a secret agreement between China, which backs the Pol Pot guerrillas, and Vietnam, which supports the Phnom Penh Government, that each party would retain its military organization until the general election. At the meeting each party accepted a 70% arms reduction.

Mr. Hor Sothoun, the son of Hor Hnam Hong, Phnom Penh’s Foreign Minister, explained the government’s policy in place of his father, who was too busy to meet me.

Q: What do you think of the agreement?

A: We chose to stop fighting and be happy rather than to continue fighting and be miserable. As long as you live on this earth, you cannot oppose America.

Q: Settlements seem to have come faster these past two years. Is there any reason for this?

A: I think it’s because China and the Soviet Union have made progress in their diplomatic relations, so that China has become reconciled with Vietnam. A western newspaper recently said in an article titled“Red Solution”that if those two big powers hadn’t compromised, Cambodian peace wouldn’t be possible, at least, not yet.

Q: Don’t you mind accepting Pol Pot?

A: We can never trust Pol Pot one hundred percent, so we cannot give up our arms one hundred percent. We decided it’s all right to fight Pol Pot in the general election under the UN surveillance. Then it will be the UN’s responsibility when Pol Pot violates the election results and moves militarily against us.

Q: Doesn’t the West misinterpret you because the other three parties have UN seats?

A: We adopted liberalism in 1989. You could say we’re still a dictator- ship, but we are not socialist any more. How could we really embrace socialismafter all that our citizens suffered under the unspeakable socialism of Pol Pot? As a by-product of liberalism, the distance between the rich and the poor has widened. It is extremely difficult to achieve equality even in any developed countries in the world.

Q: What about Japan’s participation in UN peace Keeping Operation?

A: That’s a domestic issue for Japan. If I may make an observation, however, given the present international climate, Japan may have to accept it, just as we had to meekly disarm following the UN plan. Anyway, I personally believe what the Emperor said in his speech during his tour of ASEAN.

FREEDOM

In Cambodia a foreign journalist is always accompanied by a guide and interpreter from the Press Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In case of tourists, a guide from the Tourist Bureau takes care of the group during their stay in the country. Individual tourist visas are never granted. It is quite natural for a journalist to wonder whether the government is trying to hide something.

Although it may have seemed a little rude, I asked Mr. Hor Sothoun, the chief of Press Bureau, about this. “Has any journalist been kidnapped or killed since the liberation in ’79?” he asked in return. “Think about it! If a soldier or policeman should stop you and you didn’t have the proper permits for travel andcoverage, if you couldn’t speak Khmer enough to explain yourself, you might be arrested as a spy. We are still in an emergency situation. The war hasn’t ended yet.”

My guide was Mr. L (39). It was my second time to work with him since March.A lot depends on individual character, but my guide five years ago trembled with fear just to visit one of the poor areas of Phnom Penh, probably because he thought it was a “shameful aspect of Socialism.” Mr. L was stumped by the topic of his government’s bribery but he didn’t deny it.

Though I felt sorry for Mr. L, on my second night in Phnom Penh, I went by myself to visit a 48-year-old government employee. “There is no freedom at all,” he told me. “I can’t say exactly what is not free, but at least we know that we are no free. Under Pol Pot we were not at all able to talk frankly even among friends because anyone, even an official would have been killed if he had said anything about politics. To inform on such a person was highly regarded as a sign of patriotism. No one has forgotten that fear. Not even me. I can’t trust either the present government nor my neighbors one hundred percent.” This government employee had been an officer during Lon Nol’s time. During the Pol Pot era his parents and a sister were killed and he was forced to work in the countryside gathering the juice for making palm sugar.

During those dark years, the electricity was totally destroyed, and it hasn’t yet been restored except in central Phnom Penh. As I walked away from his house in total darkness, I felt the huge gap between what the Press Department seemed to characterize as “Cambodian Glasnost” and his words: “Please wait one more month. After the UN observers arrive, I think I will be able to tell you a little more, so ……”

HISTORY VANISHING

The Tuol Sleng Museum was originally a high school, but from 1975 fro three years and eight months it was used by the “S21 Public Peace and Order Office” as a Pol Pot prison. In that building, surrounded by barbed wire, at least fifteen thousand “political criminals” were “punished.” Now the museum exhibits photos, confessions, and personal documents of those prisoners, as well as the tools of torture used on them.

In Choeung Ek Village, about fifteen kilometers southwest of Phnom Penh, in 1989 a Vietnamese architect built a commemorative tower and about ten thousand skulls which had been dug from the shallow grave of the victims of the S21, are installed in. Both of these historical sites, Tuol Sleng Museum and Choeung Ek Village, give foreign visitors an unforgettable shock.

It seems that a tacit order to replace the term “genocide” with “interrogation”was issued in the Phnom Penh government. It is quite different from the Japanese government’s substituting “invasion” for “advance” in textbooks when describing the Japanese policy in prewar China because in this case, the victims of the genocide were none other than citizens of Cambodia itself.

“Even Auschwitz has been properly preserved,” the staff member pointed out, disgusted with Phnom Penh’s timidity. “Pol Pot’s genocide is irrefutably the truth. They don’t need to be so concerned about saving face for Pol Pot, even though the Khmer Rouge is coming to Phnom Penh as a member of SNC. The Phnom Penh government may have depended on Soviet Union and Eastern Europe but that assistance dropped to only one tenth of what it had been. Phnom Penh has managed to survive somehow on virtually nothing for twelve years. Why doesn’t the UN recognize their actual accomplishments? This government controls seven and a half million people, but there are only three hundred thousand on the Thai border in UN camps, receiving plenty of support from donations from around the world.” Since I promised not to mention his name, this man with more fifteen years’ of fund-raising experience continued criticizing and pointing his finger directly at the United Nations.

In Phnom Penh’s invitation to the international community to tour the museum and mass grave I could not help but see a small but clear and justified objection to the pressure they were under to erase the history of genocide.

VOTING FORCAST

“I only saw Heng Samrin on television when I went to the factory in a neighboring village, but Price Sihanouk came here in person and gave us clothes.” Mrs. Chaia Oon (68), a rice farmer from the outskirts of Phnom Penh, was selling cigarettes and home-made sweets from a bench by the country road. When I bought a stick of sugar cane with a hundred-riel note, she gave me back several tenriel notes. Those small bills are seldom seen nowadays due to inflation.

“Just yesterday, a group of people crying ‘Thief!’ chased two men riding a motorbike along this road. Not for the first time either. It was the third time this year. In Prince Sihanouk’s time, I never saw such problems. We could go anywhere freely, and we could go out even after dark. I went to Angkor Wat in those days too.” Oon lived along the road which Sihanouk often used and was proud to have seen him with her own eyes more than ten times.

“Until two weeks ago the water was up to my chest, so I had to stack one bench on top of another and cook on top of that. Look!” she said, as she removed a banana leaf that hid the burnt part of the bench. “Farmers are really suffering,” she complained as if longing for the “good old days,” “but the government doesn’t help us at all.”

“I prefer Heng Samrin,” her next door neighbor, Mrs. Van Rose (32) interjected, “who rescued us from ‘a mass grave.’ All the time we were suffering so terribly, the Prince was travelling to foreign countries.” Her father and uncle had been imprisoned for refusing a job because they wanted to protect their cow which was exhausted from pulling a cart the whole day. Her uncle died in prison.

“If the CIA gives money to buy the voters,” Mr. L, the guide from the Heng Samrin Government suggested, predicting the election results, “Son Sann will take twenty. If Sihanouk doesn’t maintain his neutral position of chairman, his party will get thirty to forty percent. Pol Pot will get some five percent at most. Each party will split into a few factions because of contradictions in their platforms and profit-seeking,” he continued as if saying, “an annoying time is coming.” “Our party? More than ninety percent of all Cambodian citizens live in territory we govern but the people’s life in Cambodia is so hard that many would be attracted by unrealistically sweet propaganda. Therefore,” he estimated calmly, “we could get thirty or forty percent.”

On our way back to the capital, we saw a crowd of men under a tree betting on a cock fight and a line of young women in front of a movie theater, in spite of it being a weekday. Mr. L smiled sardonically,”If anybody tried to make them tighten up a little, they would run away to the three parties on the border.”

ROUTE NO.5

At seven o’clock in the morning, a blue four- wheel-drive Toyota came to pick me up. We traveled along Route No.5 to the Thai border. Mr. L of the Press Department, his driver, and two sharp-eyed men with AK-47 machine guns were in the car.”These are our body guards,” Mr. L said, introducing the others. “They are policemen from the Ministry of the Interior,” I wondered if they were Cambodian ‘KGB’ and why it was so dangerous even after the truce of May first.

After leaving Phnom Penh the condition of the road was quite good for a while,but Route No.5 looked like an endless bridge across the sea. On the right, the eastern side, that was to be expected, because the road skirts the largest lake in Southeast Asia, Tonle Sap. On the left as far as the eye could see, there was another huge lake where none belonged. It was a tranquil scene with people fishing by casting nets while others gathered lotuses from canoes made of palm trees. Underneath all that water the precious paddy was annihilated.

Thirty minutes from the capital, new mosques appeared along the road. A few were still covered by scaffolding. We stopped the car in Toul Ngok, a village of the Moslem Cham people who total about four percent of Cambodia’s population.

“If you didn’t eat pork, you were killed in Pol Pot’s time like the people in this picture,” Koup Kop (38) said, showing me a sepia-toned photo taken in front of old mosque, “I am the only survivor.” That building was destroyed during the Pol Pot era, but has been replaced by a newly completed white mosque rebuilt on the same site with the donations of one hundred fifty-five families.

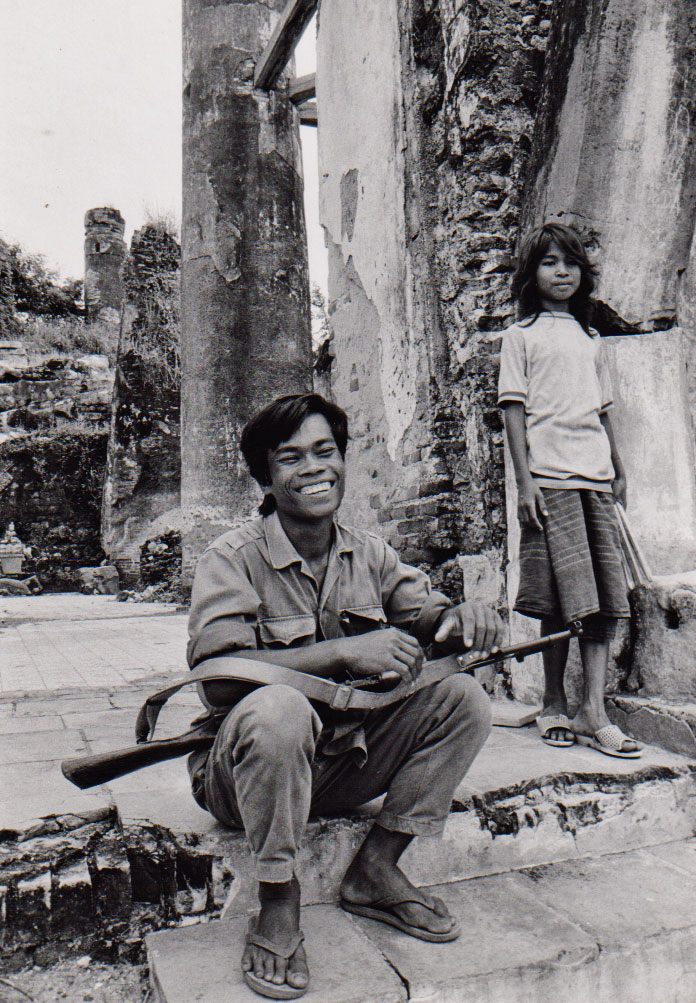

Nest we stopped at a hill to visit the symbol of Odong, very steep stupas that seem to reach to heaven. “Guarding this Pagoda is my duty.” King Kun (25) told me, as he shouldered his gun and guided me joyously around the precincts. “I am protecting a National Treasure of Cambodia.” After he was injured in 1989 in Battambang by an enemy B-40 rocket and discharged, he returned here to his hometown and was nominated by the committee to be a guard. He keeps an eye out for illegal activities such as logging, wild animal poaching, theft of cultural assets, and attacking worshippers. He is vigilant, but the Khmer Rouge haven’t attacked since the forces of Heng Samrin and Vietnam, completely emancipated this area.

Still, the ancient capital of Odong is in miserable condition. In the roofless main hall the only indications left of the great image of Buddha are its platform next to a mountainous pile of rubble, an engraved goddess, and some arabesque designs.

Clad in a sarong, holding an ancient gun that looked more like a curio than a proper weapon, an old soldier approached. Mr. Bun Phai, sixty four, carried a CKC, the single sniper used by the Soviets and China during World War II.

“That site was once called ‘Japanese Village’, he said, pointing to what looked like mere jungle to me. Thus he began to talk about old times. Before the Pol Pot era there had been a Japanese Army warehouse there and a house roofed with Japanese tiles reproduced by copying one imported from Thailand. A Japanese officer and his Khmer wife had lived in the house for many years.

“HEITAI-SAN (Japanese soldiers) never violated us like the Khmer Rouge did. The work was very hard but they gave a worker seven hundred fifty grams of rice and some dried fish every day. They also paid us every month. On payday, we drank along with HEITAI-SAN. We gambled with cards, danced with girls, and really lived it up.” Mr. Bun Phai’s reminiscences of those days when he was working on the Japanese air field construction were inexhaustible.

Wanting to see his reaction, I explained the Japanese government’s bill to send Self-Defense Forces. “They gave us independence then, and they will root out the Khmer Rouge for us now, won’t they? We will welcome them with NUNMANCHONG the same as before.” Nunmanchong is a kind of Khmer noodles similar to Japanese noodles called UDON. Because its pronunciation was difficult for them, Japanese soldiers just called it “Odong,” the name of the town.

On the way back to the car, Mr. L commented, “Generally speaking, France is unpopular because the French forced us to use the alphabet as they had done in Vietnam.”

In Campong Chhunang, a town on Tonle Sap, we took a break for lunch. The sun flag trademark on the tinned tuna fish immediately attracted our attention at a colonial-style French sandwich stand. “Donated by the Government of Japan. Not for Sale” was printed on the label. These tins are distributed in all the camps of the three Cambodian parties along the Thai border. There are two types of tinned tuna; the red label indicates tomato sauce and white, plain oil. Both are on sale at the stand. In a supermarket in Japan they are the same price, around five hundred yen, but here the red one is only two hundred riel while the white one is twice that. Ketchup flavor seems to be unpopular here. Originally free, the tinned fish has steadily risen in price while passing through many hands after leaving the camps. We lunched on the “rare article” freed from a refugee camp.

We finally reached Pouthisat. Here Route No.5 forced even our four-wheel-drive to weave all over the road to avoid the huge potholes. At anything over ten kilometers an hour, the passengers bounced and bumped their heads on the roof. The road was worse because some of the old pavement remained. Although I thought that a simple muddy path would be much better, there was no other route.

Route No.1 between Phnom Penh and Ho Chi Minh City is also a national road of Cambodia, but it has been maintained in good condition by Soviet aid. The journey between the two cities takes only four hours, not counting waiting time at the ferry and the border. Route No.5, where we had tough going, was originally constructed by France in the 1920’s but the Khmer Rouge dug deep ditches every twenty meters to obstruct American forces supporting Lon Nol. Since then, tanks and other heavy vehicles have tranquily travelled on this “road to the west,” but no aid for repair has come from the East.

Houses increased along the road. We came across a group of students, five boys and five girls, returning late from school because of the double-shift system.I asked what they wanted to be when they grew up. “I want to be a doctor,” one of them said. “Me, too!” cried another. I was surprised that seven of them responded, “Medical doctor.” The other three wanted to be a teacher, a policeman, and a farmer. My companion, an officer of the socialist government,grumbled, “Children of the poor will never be able to be……” Then to rush my photography, he urged, “Hurry up! There’s no time!” A curfew is still in force from seven in the evening until five in the morning everywhere in Cambodia except Phnom Penh where it is only from midnight.

We entered Battambang at twilight. About eighty-two thousand people live here in the second biggest city in Cambodia. The Sankhai River flowing through the city from Thai territory is muddy, almost like cafe au lait. “In Pallin which is controlled by Pol Pot. They are blasting the earth with a lot of water to wash rubies out of the soil,” I was told. For only two hours of coverage, it took us ten hours to drive two hundred eighty kilometers from Phnom Penh.